Archive for the ‘Praise and Polemics’ Category

Irritability is a sign of life…

IRRITABILITY: the property of protoplasm and of living organisms that permits them to react to stimuli.

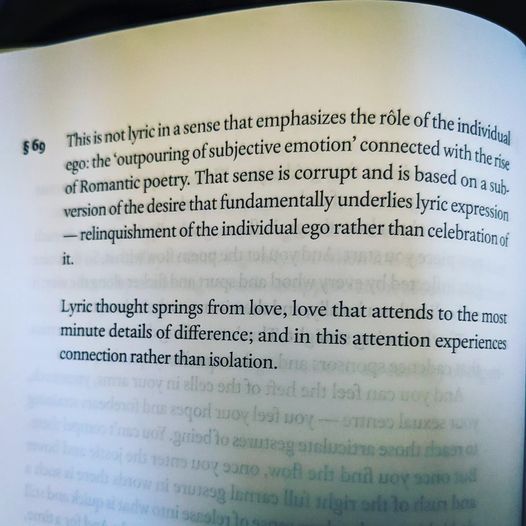

Poet (and a quite respectable poet I might add) Ralph Kolewe shared the above passage and caption this Labour Day. That it irritated me is an understatement…

That opening paragraph, with its allusion to “the ‘outpouring of powerful emotion’ connected with the rise of Romantic poetry” will twig with those readers who remember a time in the not so distant past when, imaginably as a reaction to what was perceived to be a persistent, pernicious poetic, it was de rigueur to set up a Straw Man Wordsworth as responsible. Zwicky’s wording is brow-furrowing, for it suggests that either she has misremembered Wordsworth’s actual words from the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads (“For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings…”) or that she has formulated a parody of them to gesture toward that modern tendency she has in her sights, a tendency a faint echo of the Romantic thunderclap. Surely, the more charitable reading is the latter, but then the weakness of what she would negate infects her position: how strong can it be if it needs set itself over against a mere parody of its much more sophisticated and robust progenitor?

Just what poetic tendency, then, does Zwicky have in her sights? The answer to this question likely lies in the 301 other remarks and their parallel running text of quotations that compose Lyric Philosophy, the book Kolewe quotes. I must admit, scrutinizing the cited passage isn’t very helpful: this “corrupt” sense of lyric “emphasizes the rôle of the individual ego” in an “‘outpouring of powerful emotion’,” a sense “based” on a “celebration” rather than “relinquishment of the individual ego,” an emphasis and celebration that presumably results in “isolation” rather than “connection.” Some poetry from the past six or seven decades might come to mind, but the search leads away, ultimately, from the lyric sense Zwicky would affirm, and its own, not unproblematic Vorurteilen (prejudices or presuppostions…).

First, what sense of ego is operative here? Is it the Cartesian cogito, the transcendental subject of Kant or the “I am” that accompanies all thought, or the transcendental ego of Husserl, or the ego of psychoanalysis or analytic psychology? Is it some pedestrian understanding of the individual self, or even a particular inflection of the lyric “I,” that endlessly problematic persona? An answer may lie in the context of the work from which the remark is abstracted.

More gravely, however, the thinking here seems to overlook that longstanding “relinquishment of the individual ego” in modern and even “archaic” poetries. Certain strains of avant garde poetics, from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, to the chance generated poems of John Cage and Jackson MacLow, along with William Burrough’s “Third Mind” poetics, back to Charles Olson’s “objectism” (and his explicit criticism of the place of the ego in Ezra Pound’s Cantos), the practice of the Objectivists, or the impersonality advocated by the early Eliot, or even Yeat’s masks all questioned or sidestepped the primacy of that individual ego. One could extend this line back even to the “I” in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ernesto Cardenal’s exteriorismo and Pessoa’s (and Canada’s Erin Mouré’s) heteronyms come to mind. The poetics of French Surrealism and Mallarmé’s poetry or a particular reception of Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” are apropos. And what of that obscure “I” crystallized in autobiographical shibboleths in Celan’s later poetry? More radically, even a cursory reading of Jerome Rothenberg’s assemblage Technicians of the Sacred reveals a global range of poetries, communal, divinatory, shamanic, and otherwise that spring from sources and concerns other than “the individual ego.”

My point here is not to contradict Kolewe’s enthusiasm or set Zwicky up as a Straw Person, but rather to register a particular impatience with reflections on poetics that gaze into too shallow a small pool. Poetries that sing something other than an individual self are legion. All of which leaves aside for the moment the question of the grounds for and imaginable value of a lyric practice that dwells on and in an I, if not celebrates it. Perhaps blame lies with that first modern poet, Dante Alighieri, and his making at least three aspects of himself and their poetic and eternal fate the subject of his Commedia…

On Poets and Poetry, the Living and Otherwise

A line in a recent poem of mine reads, ‘”…Dante, Hölderlin, Whitman.” “They’re dead,” they said, an absolutely modern.’

The opinion, or, more charitably, judgement, of that “absolutely modern” is one I’ve encountered and that has irked me for nearly a generation (i.e., three decades) now. The well-read reader has likely already arrayed a phalanx of arguments to skewer said opinion, and I would hope the litotic irony that underwrites my line would serve as sufficient refutation, especially as, its being Easter weekend and I’m reading through the Commedia, “I have no will to try proof-bringing.”

That being said, a poem of mine published a while back in Scrivener, touches on, if not quite addresses, the topic. I offer it here, in print and voice.

I remain fairly persuaded this intervention is unlikely to be my final word on the matter…

Grammar, linguistic and literary production, and related matters: a note for Kent Johnson

If there’s one thing that indefatigable gadfly of a poet Kent Johnson and I share it’s a stubborn, irritable tick of concern with L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry and poetics and their “post avant” wake (so wide now few poets or critics seem aware how much they operate within its horizon…).

Recently, his most recent online persona linked an article he had written for absent, “competence, linguistics, politics & post-avant matters”. Therein, he rightly takes to task Charles Bernstein et al. for their loosey-goosey way of discussing (and thinking about) language, grammar, ideology, and society. I can’t say I’m in full agreement with Johnson on all points, but the drift of his argument is surely in the right direction.

It was with no little delight I read in a recently acquired copy of Slavoj Žižek’s 2012 Less Than Nothing the following passage, which sums up pointedly and neatly the fundamental misunderstanding of language (the identification of linguistic or literary production with that of commodities) that underwrote, at least, the early days of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E:

The basic premise of discursive materialism was to conceive language itself as a mode of production, and to apply to it Marx’s logic of commodity fetishism. So, in the same way that, for Marx, the sphere of exchange also obliterates (renders invisible) its process of production, the linguistic exchange also obliterates the textual process that engenders meaning: in a spontaneous fetishistic misperception, we experience the meaning of a word or act as something that is a direct property of the designated thing or process; that is, we overlook the complex field of discursive practices which produces this meaning. What one should focus on here is the fundamental ambiguity of this notion of linguistic fetishism: is the idea that, in the good old modern way, we should distinguish between “objective” properties of things and our projections of meanings onto things, or are we dealing with the more radical linguistic version of transcendental constitution, for which the very idea of “objective reality” of “things existing out there, independently of our mind” is a “fetishistic illusion” which is blind to how our symbolic activity ontologically constitutes the very reality to which it “refers” or which it designates? Neither of these two options is correct—what one should drop is their underlying shared premise, the (crude, abstract-universal) homology between discursive “production” and material production. (7)

I am skeptical Žižek’s characteristically canny observation settles the question (one that extends back to the advent of philology (the science of language) and literature-as-such), but it is surely sharp enough to cut through much of the underbrush!

To praise, that’s the thing! Geoffrey Nilson on Lynn Crosbie’s influence

Over at many gendered mothers, Geoffrey Nilson gives some well-deserved praise to Lynn Crosbie.

Nilson begins his laudation with reference to Crosbie’s infamous, bête noire of a book, 1997’s Paul’s Case (which I would still energetically maintain is a tour de force). Where Nilson goes on to describe Crosbie’s influence on his own work and self-understanding, I would point to her exemplary 2006 poetry book Liar as another index of her singular, independent talent: at a time when only the most mannered poetry was de rigeur, Liar stood out alone as a work of fierce, fearless confession.

Read Nilson at the link above, and get and read something by Lynn Crosbie!

Praise the algorithm! Plunging into the silliness: Andrew Lloyd’s career as an Instagram poet

Thanks to real poet Michael Boughn for sharing Andrew Lloyd’s article from Vice “I Faked My Way as an Instagram Poet, and It Went Bizarrely Well”—a fortuitous addendum to my last post, “Synchronicitious Critique”.

Reflections on James Dunnigan’s ‘The Stained Glass Sequence’

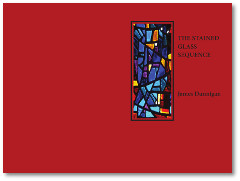

I had the chance recently to discuss how James Dunnigan’s The Stained Glass Sequence  just out from Frog Hollow Press might be received. It’s a weird poem in the context of present-day English-language poetry, with gestures and stances more reminiscent of High Modernism, intricate and allusive, than anything you might read on a visit to, say, the Poetry website….

just out from Frog Hollow Press might be received. It’s a weird poem in the context of present-day English-language poetry, with gestures and stances more reminiscent of High Modernism, intricate and allusive, than anything you might read on a visit to, say, the Poetry website….

It was the refractory complexities of just the suite’s title that made me think “How someone who reads poetry can review it is just beyond me….” which I posted on social media, which, in turn, received (among others) a telling reply: “It is a form of reading, at best.”

Taken by itself (the thread did wind on…), this response can be taken to be representative in several ways. First, it assumes the spontaneous authority of the vulgar usage of the verb ‘to read’, an authority that in certain regards is beyond reproach but which is also constantly in danger of asymptoting to the thoughtless. More significantly it enacts precisely what my original post found problematic, since it seems either to refuse or fail to register the stress on ‘reads‘ indicated by the italics (to suggest the word twists in some way from the ordinary sense) and the claim made in the predicate (which further torques the notion of reading from its accepted sense); that is, it doesn’t read or try to understand the original post, seeming more concerned to leave everything the way it is, its complacency disturbed just enough to defend the status quo and defer reflection.

In the same way, many readers will no doubt pass over the implications of the title. If there’s one dogged misperception that has persisted since the late Eighteenth Century it’s the Baconian idea that the word is or should function as a transparent medium, a window onto the world, a notion the title troubles doubly, for stained, unlike transparent, glass, though translucent, colours what might be viewed through it, and, more importantly, its pieces are a medium to compose a design or picture the window frames rather than a view through it. To borrow a two centuries’ old terminology, the title suggests the sequence’s language not so much represents but presents. Any reading, let alone evaluation, of the sequence that fails to assiduously and consistently treat the language as refractory rather than transparent will fail to appreciate it in the first place.

Of course, such reflexivity, a gesture that goes back to Homer, is only a start to the title’s formal sophistication. Its grammar, likewise, throws light on the poem: it is composed of a substantive (‘sequence’) preceded by three modifiers (‘The Stained Glass’…). If one considers the middle two words in themselves, in the etymology that roots their adjectival function, they, too, possess the same syntax, a substantive ‘glass’ modified by ‘stained’. This is to say, the syntax of the title, in a way, is nested, or, better, framed, the way the implications of the title arguably frame, or should, the reception of the poem.

And reading the sequence, the attentive reader will remark how little stained glass or stained-glass windows actually appear in the poem. The sequence opens ekphrastically, describing a painting by Chagall, stained glass is mentioned as such in the second part, the fourth section is in four “panels”, and Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel are remarked in the fifth. That the poem makes far more consistent reference to painting than stained glass suggests all the more the formal reflexivity of the title than its naming “an important theme” that the sequence takes up and develops.

A careful, thoughtful reader may well mark, too, another complication. The title is, in a way, paradoxical, modifying a temporal noun (‘sequence’, a pattern than unfolds linearly in time) with a spatial modifier (‘stained glass’, a translucent medium that either colours light or is itself used in the composition of a design or picture, a work of art perceived spatially). There is then a tension, as the sequence is, perhaps, a series of spaces arranged in time, though the title names the sequence as a sequence, as a temporal form, as language itself is.

Any reading of Dunnigan’s book that fails to read (in the most emphatic sense) even the title will likewise falter in understanding the sequence the title frames and thereby governs. And if so much is at work even before the first word of the poem is read, let alone on every line, if this reader is a reviewer, how little weight will their judgement carry if they fail to register these first—preliminary, guiding, essential—aspects of the poem?

“To praise–that’s it!”

Canadian poet Patrick Lane passed away today at the relatively young age of 79.

Though I never knew him personally, he was an eminent figure in Saskatchewan during my years as an apprentice poet, along with his partner Lorna Crozier, John Newlove, Andrew Suknaski (all three of whom I was lucky enough to learn from personally), Barbara Sapergia, and Geoff Ursell, among others, and I heard him read on a number of occasions.

What strikes me now is how quickly many have expressed their shock, grief, and appreciation for the man and his writing, which is as it should be. However, it seems to me that such praise shouldn’t have waited until it was too late for him to have heard or read it and appreciated it (though he did receive many accolades during his lifetime).

If you read a poem that knocks your socks off, or a book of poems, or a book-length poem, these days you can tell the poet how much you appreciate their work at the speed of light (depending on your data package). I’d encourage you to do so. The poet will appreciate it more, now, than wreaths of belated praise heaped upon their legacy once they’re gone.

“The poetry wars never ended.”

Chicago Review has just posted a lively, provocative conversation with Kent Johnson and Michael Boughn about the motivations driving that equally lively web-journal Dispatches from the Poetry Wars.

Chicago Review has just posted a lively, provocative conversation with Kent Johnson and Michael Boughn about the motivations driving that equally lively web-journal Dispatches from the Poetry Wars.

At a time when Instapoets are lionized as The Big New Thing (because of their sales numbers) and the art is otherwise domesticated (in the MFA program and English class), I know of few more vital, critical, and necessary sites of resistance than Dispatches.

“…voices / …heard / …as revelations”

Interested parties can read a talk I gave at the Spirituality in Contemporary Canadian  and Québécois Literature Panel at the annual meeting of the Association for Canadian and Quebec Literatures, Regina, Saskatchewan, 27 May 2018.

and Québécois Literature Panel at the annual meeting of the Association for Canadian and Quebec Literatures, Regina, Saskatchewan, 27 May 2018.

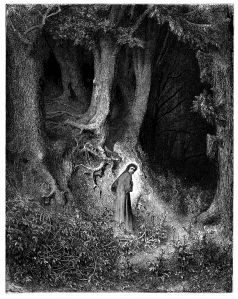

“Ahi, quanto a dir qual era è cosa dura…”: a note on the postmodern Dante

Any visitor curious enough to view the reading that launched March End Prill might have  been in equal parts mystified and amused by my describing Cervantes and Homer as “avant garde, reflexive, or postmodern”. If so, then they’d be equally quizzical of my describing Dante as postmodern.

been in equal parts mystified and amused by my describing Cervantes and Homer as “avant garde, reflexive, or postmodern”. If so, then they’d be equally quizzical of my describing Dante as postmodern.

I’ve made it a ritual to read through Dante’s Commedia every Easter Week “in real time”, The Inferno Good Friday and Holy Saturday, The Purgatorio Easter Sunday through to Wednesday, and The Paradiso as I will, as, having left the earth, terrestrial time no longer applies to the Pilgrim Dante or, in this case, his reader.

One of the things that makes Dante’s epic a classic is that even returning to it annually in this way, even the most familiar passages give up hitherto unnoticed features and meanings. Such was my experience this year, rereading the opening lines of The Inferno:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

ché la diritta via era smarrita.

Ahi quanto a dir qual era è cosa dura

esta selva selvaggia e aspra e forte

che nel pensier rinova la paura!

Tant’ è amara che poco è più morte;

ma per trattar del ben ch’i’ vi trovai,

dirò de l’altre cose ch’i’ v’ho scorte.

Midway in the journey of our life

I came to myself in a dark wood,

for the straight way was lost.

Ah, how hard it is to tell

the nature of that wood, savage, dense and harsh —

the very thought of it renews my fear!

It is so bitter death is hardly more so.

But to set forth the good I found

I will recount the other things I saw.

A simpler, more literal rendering of line four would be “Ah, how to say what was is a hard thing…”.

Arguably the most immediate way to take this line is that the Pilgrim-Poet Dante, recounting his experience relives the fear he felt lost in that wild wood (delightfully, in the Italian, esta selva selvaggia), which causes a moment of reflection wherein he (reflexively) writes, not about the wood or his fear, but about his writing about the wood and his fear. That is, “it is difficult to write about so fearful an experience, because writing about it requires I in a way relive that fear”.

But, of course, the persona of the Pilgrim is a mask worn by the poet Dante. Considered from this angle, the poet is writing about writing his poem. This admission of the challenge of the epic task the poet has set for himself and the demands that this project place upon the poet’s talent is a pattern that recurs throughout the Commedia, most immediately and movingly in the next canto, where the Pilgrim questions his worthiness to follow Virgil through Hell and Purgatory and receives so tremendously a moving, eloquent pep talk in reply that, in all sincerity, it never fails to move me to tears. However much such an admission of humility is a rhetorical ornament common in Latin literature, it is no less moving, such is Dante’s genius. It is as if, then, the poet were admitting, “Ah, how hard it is to write this epic poem in this noble style I invented just for this purpose.”

The rich complexity of this line, however, is hardly exhausted in this near cliché example of the “postmodern” text’s referring to itself in however a sly, metapoetic manner. A quick glance back at the English translation of this line and its tercet reveals a curious pattern: as the tercet progresses the translation becomes more literal. The Italian grammar of the line is, or so I have it on relatively good authority, somewhat counter intuitive to an English speaker, for ‘qual‘ that I translate as ‘what’ is a word that can function as either a relative pronoun or an interrogative, closer to English ‘which’. Moreover, the line conjugates the copula in both the past and present tenses: “era è“, “was is”. Why various English versions of the line depart from the Italian as the syntactic demands of the remainder of the tercet demand is understandable. But it strikes me, perhaps only because of my depending on English translations and a casual commentary on the Italian grammar, that the line, describing difficulty, is, itself, linguistically difficult, a stylistic device that recurs in The Inferno. Here, then, the artistic awareness of the poet extends into the very syntax of his language.

Nevertheless, there is no small irony in the progression of the tercet. On the one hand, the Pilgrim-Poet admits to the emotional and poetic difficulty of presenting what he wants to present, but that “hard thing” (cosa dura) is, in a sense, dispensed rather too easily with three conjoined adjectives selvaggia e aspra e forte, savage and dense and harsh, followed by the simple, frank admission that remembering it renews his fear. For something so dura, hard, it is performed with a strikingly easy fluency. On the other hand, though, it could be that the remainder of the canto that deals with the Pilgrim’s encounter with its famous three beasts, the Leopard, Lion, and Wolf, and his being forced by them into darkness and despair is just that “hard thing” whose memory so frightens him (and fear is an important theme in these two cantos and throughout the Inferno), or it might be the Pilgrim-Poet rushes over that memory to pass through it and leave it behind to get to that more heartening good his being lost and finding his way through Hell and Purgatory to Paradise provides.

That Dante’s poem should display such deft and complex linguistic self-consciousness, a metapoetic dimension literary scholars have pegged as characteristic of postmodern literature, really shouldn’t be a surprise, for the work of literature that is at the same time about itself and literature was first theorized and intentionally explored over two centuries ago by the German Early Romantics, die Frühromantiker, in their journal The Athenaeum (1798-1800) and in their criticism, letters, poems and novels. Indeed, the three characteristically “modern” writers for the Jena romantics were Goethe, Shakespeare, and Dante.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment