OULIPO now and then

“Oulipo turns 60, but given how much we hear about it these days, it feels more like 150″ says George Murray at Bookninja. To some of us, it seems much older.

For my part, I learned about the OULIPO and composition by means of a generative device in the early nineties, thanks to Joseph Conte’s goldmine of a study, Infinite Design: The Forms of Postmodern Poetry. Not that long after (or so it seems this morning), Christian Bök’s Eunoia appeared to equal acclaim and, well, annoyance (a book, for those who don’t know, is composed by means of a generative device, after the OULIPO).

For me, the controversy was tiresome, having read Conte’s work and, more importantly, Ernst Robert Curtius’s classic oeuvre, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, which details ancient and medieval modes of composition which quickly dispel any illusions the OULIPO and its epigones are avant garde. (Though I do know that matter is more complex than I allow for here).

I expressed my impatience with the whole matter, boiling Curtius’ excurses into the following poem from Ladonian Magnitudes, one among several that got up the nose of that book’s most notorious reviewer. The poem is four quatrains and a concluding line, despite WordPress’ formatting constraints…

Liposuction & Related Procedures in Antiquity

Lasus Pindar’s master made a poem sans σ and a millennium later

Nestor of Laranda in Lycia wrote an Iliad each book less a letter Tryphrodorus Aegyptus did the Odyssey

So from Baroque Spain via Peter Rega

From Fabius Planciades Fulgentius’ De aetatibus mundi et hominis λειπoγραμματoς

Hucbald’s Charles the Bald eclogue beginning every word with C one-hundred and forty six lines

Late Roman grammarians’ παρόμoιoν

O Tite, tute, Tati, tibi tanta, tyranne, tulisti a scolia for a Caracalla’s Banquet

where as Aelius Spartianus has it from his brother Geta every dish alliterated

The so-called “figure poems” τεχνoπαίγνια in the Greek Anthology

Porfyrius Optatianus rendered in Constantine’s Latin

Alcuin, Raban Maur, Sixteenth Century Hellenism followed

Pre-Alexandrian Persian lines in trees and parasols

Eusonius follows Plato’s for the Sophists logodaedalia in his Technopaegnion

Each line of one poem starting and finishing with one syllable and the last word’s the next’s first

Catalogues of single syllable limbs, gods, foods, questions “yes” or “no”

A myth crib every line turning on one syllable

Grammatomastix’s monosyllables amputated prefixes lifted from Ennius and Virgil

The “versos de cabo roto” Urganda chants before “…a certain village in La Mancha…”

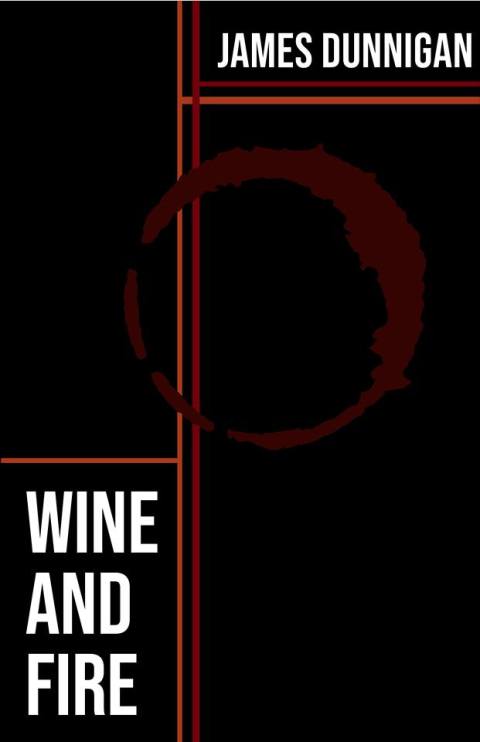

James Dunnigan: new chapbook & interview

Design: Bianca Cuffaro

James Dunnigan launches his second chapbook Wine and Fire (Cactus Press, 2020) Tuesday 18 February 2020, 20h00 at the Accent Open Mic Vol. 25—Cactus Press launch, La Marche à côté, 5043 St-Denis, Montreal, Quebec. (Facebook Event page, here).

Dunnigan is also the author of The Stained Glass Sequence (Frog Hollow Chapbook Award, 2019) and was shortlisted for the Gwendolyn MacEwen Poetry Prize in 2018. His work has also appeared in CV2, Maisonneuve Magazine, and Montreal Writes. He writes in English and French, reads Latin and sells fish for a living.

You can read a series of five mini-interviews with him, here.

You can see and hear a recent reading, here.

Dunnigan is a singularly gifted young poet. If you’re in Montreal, this launch and this chapbook are not to be missed.

Critical Fragment

If we judge a writer’s worth in the first instance on their identity or character, we avoid, evade, or void the work (and, arguably, reward) of reading (which is trouble enough) and engaging the work, which is to short circuit the critical task.

“Apology for Absence”

At a reading I attended at the end of last year, a poet friend (very supportive of my work) asked if I’d retired.

I understood her to be referring to my not having worked the past three years. I was in chemotherapy the last half of 2016, and I’ve been recovering ever since. My vitality and acuity are presently too volatile for me to commit to teaching fifteen weeks at a go. I tried in the fall of 2018, but had to surrender the single class I was teaching mid-November…

I was more than a little disturbed when through my mental fog it appeared to me she hadn’t been asking about my job status but my writing and publication record. (That it took me so long to pick up on her meaning is an index of my state). My last trade publication was March End Prill (Book*Hug, 2011), a long poem that, itself, had been composed almost a decade before it appeared in print.

Lately, I’ve taken to joking I have the creative metabolism of a pop star: about twelve poems a year, which, were I pop singer, would be enough for a new album. Given that many poetry presses prefer manuscripts of over eighty pages or so, that pace of production would ideally result in a new book every seven years or so. Were it only so simple.

Even for someone with three trade editions under his belt, every new manuscript is a new challenge to get published. Indeed, the last two collections I’ve collated have failed to find a publisher. On the one hand, I’m no networker. On another, the work has always been against the grain. Tellingly, the last editor to turn down my latest manuscript did so on the basis of an understanding of its poetics the opposite of my own.

Moreover, I eschew a practice increasingly common, to compose “a book”. Often a poet will pick up and follow the thread of a theme or as often crank a generative device. Sometimes such efforts are successful, and I can appreciate the urge and sentiment that goes into this approach, when it’s not the result of the pressures of reigning expectations. However, as my earliest mentor once quipped concerning the composition of a collection: “A book is a box.”

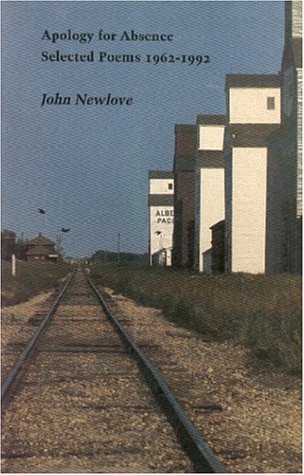

Which brings me to the title of this post. Apology for Absence is the title of John Newlove’s  selected poems (Porcupine’s Quill, 1993), a famously laconic poet, known, among other things, for his diminishing productivity over the years. But Newlove holds a more profound importance for me, personally. As I write in a poem from Ladonian Magnitudes:

selected poems (Porcupine’s Quill, 1993), a famously laconic poet, known, among other things, for his diminishing productivity over the years. But Newlove holds a more profound importance for me, personally. As I write in a poem from Ladonian Magnitudes:

Because John Newlove the Regina Public Library’s writer-in-residence gave me his Fatman and reading it in the shade on the white picnic table on the patio in our backyard thought “I can do that!” and wrote my first three poems

I like to think that happened when I was fourteen, but a little research proves I must have been a year or two older. At any rate, however much I admire and envy the productivity of a D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Bernhard, I seem to have followed Newlove’s example in this regard. (It’s a long story). Poetically, there are worse models.

No, I haven’t retired. Nor am I absent, MIA. I’m hard at work, at my own work, going my own direction at my own pace, trusting some will be intrigued if not charmed enough to tarry along.

To praise, that’s the thing! Geoffrey Nilson on Lynn Crosbie’s influence

Over at many gendered mothers, Geoffrey Nilson gives some well-deserved praise to Lynn Crosbie.

Nilson begins his laudation with reference to Crosbie’s infamous, bête noire of a book, 1997’s Paul’s Case (which I would still energetically maintain is a tour de force). Where Nilson goes on to describe Crosbie’s influence on his own work and self-understanding, I would point to her exemplary 2006 poetry book Liar as another index of her singular, independent talent: at a time when only the most mannered poetry was de rigeur, Liar stood out alone as a work of fierce, fearless confession.

Read Nilson at the link above, and get and read something by Lynn Crosbie!

Corpus Sample: the poetic Wittgenstein

A friend recently got a hold of the first and only book published during philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s lifetime, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. I don’t know what prompted my friend to order in a copy, but he was understandably perplexed; even Bertrand Russell famously failed to understand his student’s work. Philosophically, despite its immediate fame among the Logical Positivists, the Tractatus is, today, a “dead dog”, repudiated most famously by the author’s own reflections, published posthumously as the Philosophical Investigations. Nevertheless, a friend of my friend sought to console him, assuring him “the Tractatus is pure poetry.” Creative writers have tended to agree: Jerome Rothenberg and John Bloomberg-Rissman included sections from Philosophical Investigations in their assemblage of outsider poetry, Barbaric Vast & Wild, dramatist and novelist Thomas Bernhard published Wittgenstein’s Nephew in 1982, and Canadian poet-philosopher Jan Zwicky’s first book Wittgenstein Elegies appeared in 1986.

I don’t remember when I first encountered Wittgenstein, but it was surely before beginning my undergraduate studies. Those (eventually) were devoted to philosophy, and I wrote my honours paper on the private language argument in the Philosophical Investigations. To pass the time (four days) driving from Regina to Montreal, where we were going to study, a friend and I read through the Tractatus, doing our damnedest to make what sense of it we could. And my graduate studies resulted in a number of poetic texts, all engaging in various ways with the early and late Wittgenstein. Even more recently, a compositional method shared here takes an ironic inspiration from his remark that “meaning is use”.

I post below, then, two poems now included in my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central. The first is a prose poem, borrowing liberally from Norman Malcolm’s memoir; the second is a poem that tries to come to terms with the Tractatus.

[from “Grand Gnostic Central”]

The walls are bare and the floor scrupulously clean. In the living-room, two canvas chairs and a plain wooden one around an iron heating-stove. In the other room, a cot and card-table, books, papers and pen. A man sits at the card table. His face is lean and tanned. He wears a flannel shirt and light grey flannel trousers. His shoes are highly polished. He looks concentrated and severe, striking out as if arguing. He stops, sits still. He remembers swimming—a small boy, the ease of floating, the sun and water in his eyes, closing them tight. He remembers how hard it was forcing himself down, down deep to the mud at the bottom, the water always pushing him back to the surface, his needing air pushing him back to the surface. He has written a treatise on logic. He knows those who do not know him think him an old man, irritable and obscure. He remembers writing his thoughts for the book in small notebooks he carried around. He remembers writing “If `the watch is shiny’ has sense…” He remembers the flash on the watch-face that gave him the example. It had rained and only now the sun cut through red clouds. The field’s mud is soupy and slick. He crouches down in the water at trench-bottom, once almost standing to keep his balance in the muck. He hears the sharp tiny ticking at his wrist. He dates the entry 16.6.15.

Holy Crow Channels LW

We know no sensations

give these propositions sense. Questions

that exact innocence free from naivete

demand a rigorous ignorance of the evident

apparent given as the one condition

for their initial

stuttered utterance.

The long tautology that bends say

the blade of a jet engine

to just the angle of most force

turns on this

when the need for further thrust

draws inertia from the potential

for doubt, unbinding concepts and arguments

and baffling mathematicians

just this side of mathematics.

We need our end to be

the final determination

of the rule that keeps stasis

appearing repeatedly, that blesses with some semblance

of regularity frequently enough

to let us see this

and hear that

completely unsurprised. These things we know

are hardly thought, for the common

is the category entered most

easily. We can count, yet,

to ask what numbers are

reveals the path that eases

the passage everywhere but where

the answer you expect to desire lies

and leads you to question

again the writings that made you

conclude the first proposition

that defined one doubtfully. For them

a mere analysis, for you

something more that flails you

to what is truly necessary. The clear thought

expressed as clearly as the fabric of language

will strain it

fascinates you with its immaculate muteness

that finally becomes a song so mythic

you are bound from it, fast,

and your hearing is filled

with what is spoken

in innocence, naively.

Action Books action

As an English-language Canadian poet, I’ve always starved and thirsted for almost anything foreign to most of what officially passes for my native poetic tradition. Action Books has been introducing some of the wildest, weirdest, far-outest poetry into English for years, and now their list is half price (with the checkout code ‘TRANSLATE’).

Do yourself and them and North American English-language poetry and line your shelves and blow your poetic mind now!

Manifesto

Action Books is transnational.

Action Books is interlingual.

Action Books is Futurist.

Action Books is No Future.

Action Books is feminist.

Action Books is political.

Action Books is for noisies.

Action Books believes in historical avant-gardes.

& unknowable dys-contemporary discontinuous occultly continuous anachronistic avant-gardes.

Art, Genre, Voice, Prophecy, Theatricality, Materials, the Bodies, Foreign Tongues, and Other Foreign Objects and Substances, if taken internally, may break apart societal forms.

“In an Emergency, Break Forms.”

Action Books: Art and Other Fluids

Praise the algorithm! Plunging into the silliness: Andrew Lloyd’s career as an Instagram poet

Thanks to real poet Michael Boughn for sharing Andrew Lloyd’s article from Vice “I Faked My Way as an Instagram Poet, and It Went Bizarrely Well”—a fortuitous addendum to my last post, “Synchronicitious Critique”.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment Back in 2008 (!), I had the good fortune to meet (among others) a then-younger scholar of Amerikanistik,

Back in 2008 (!), I had the good fortune to meet (among others) a then-younger scholar of Amerikanistik,