Archive for the ‘Lyric Philosophy’ Tag

Irritability is a sign of life…

IRRITABILITY: the property of protoplasm and of living organisms that permits them to react to stimuli.

Poet (and a quite respectable poet I might add) Ralph Kolewe shared the above passage and caption this Labour Day. That it irritated me is an understatement…

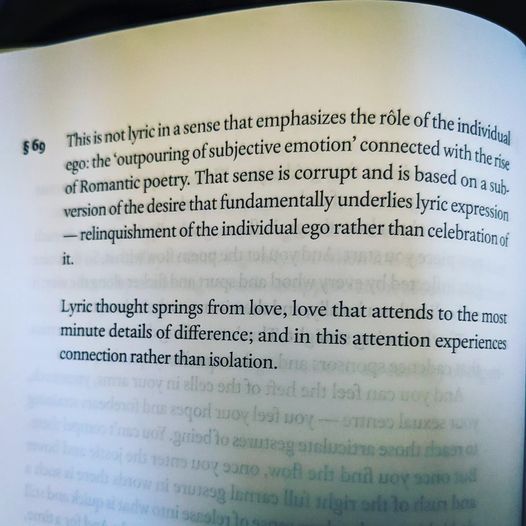

That opening paragraph, with its allusion to “the ‘outpouring of powerful emotion’ connected with the rise of Romantic poetry” will twig with those readers who remember a time in the not so distant past when, imaginably as a reaction to what was perceived to be a persistent, pernicious poetic, it was de rigueur to set up a Straw Man Wordsworth as responsible. Zwicky’s wording is brow-furrowing, for it suggests that either she has misremembered Wordsworth’s actual words from the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads (“For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings…”) or that she has formulated a parody of them to gesture toward that modern tendency she has in her sights, a tendency a faint echo of the Romantic thunderclap. Surely, the more charitable reading is the latter, but then the weakness of what she would negate infects her position: how strong can it be if it needs set itself over against a mere parody of its much more sophisticated and robust progenitor?

Just what poetic tendency, then, does Zwicky have in her sights? The answer to this question likely lies in the 301 other remarks and their parallel running text of quotations that compose Lyric Philosophy, the book Kolewe quotes. I must admit, scrutinizing the cited passage isn’t very helpful: this “corrupt” sense of lyric “emphasizes the rôle of the individual ego” in an “‘outpouring of powerful emotion’,” a sense “based” on a “celebration” rather than “relinquishment of the individual ego,” an emphasis and celebration that presumably results in “isolation” rather than “connection.” Some poetry from the past six or seven decades might come to mind, but the search leads away, ultimately, from the lyric sense Zwicky would affirm, and its own, not unproblematic Vorurteilen (prejudices or presuppostions…).

First, what sense of ego is operative here? Is it the Cartesian cogito, the transcendental subject of Kant or the “I am” that accompanies all thought, or the transcendental ego of Husserl, or the ego of psychoanalysis or analytic psychology? Is it some pedestrian understanding of the individual self, or even a particular inflection of the lyric “I,” that endlessly problematic persona? An answer may lie in the context of the work from which the remark is abstracted.

More gravely, however, the thinking here seems to overlook that longstanding “relinquishment of the individual ego” in modern and even “archaic” poetries. Certain strains of avant garde poetics, from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, to the chance generated poems of John Cage and Jackson MacLow, along with William Burrough’s “Third Mind” poetics, back to Charles Olson’s “objectism” (and his explicit criticism of the place of the ego in Ezra Pound’s Cantos), the practice of the Objectivists, or the impersonality advocated by the early Eliot, or even Yeat’s masks all questioned or sidestepped the primacy of that individual ego. One could extend this line back even to the “I” in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ernesto Cardenal’s exteriorismo and Pessoa’s (and Canada’s Erin Mouré’s) heteronyms come to mind. The poetics of French Surrealism and Mallarmé’s poetry or a particular reception of Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” are apropos. And what of that obscure “I” crystallized in autobiographical shibboleths in Celan’s later poetry? More radically, even a cursory reading of Jerome Rothenberg’s assemblage Technicians of the Sacred reveals a global range of poetries, communal, divinatory, shamanic, and otherwise that spring from sources and concerns other than “the individual ego.”

My point here is not to contradict Kolewe’s enthusiasm or set Zwicky up as a Straw Person, but rather to register a particular impatience with reflections on poetics that gaze into too shallow a small pool. Poetries that sing something other than an individual self are legion. All of which leaves aside for the moment the question of the grounds for and imaginable value of a lyric practice that dwells on and in an I, if not celebrates it. Perhaps blame lies with that first modern poet, Dante Alighieri, and his making at least three aspects of himself and their poetic and eternal fate the subject of his Commedia…

Leave a comment

Leave a comment