Archive for the ‘poetics’ Tag

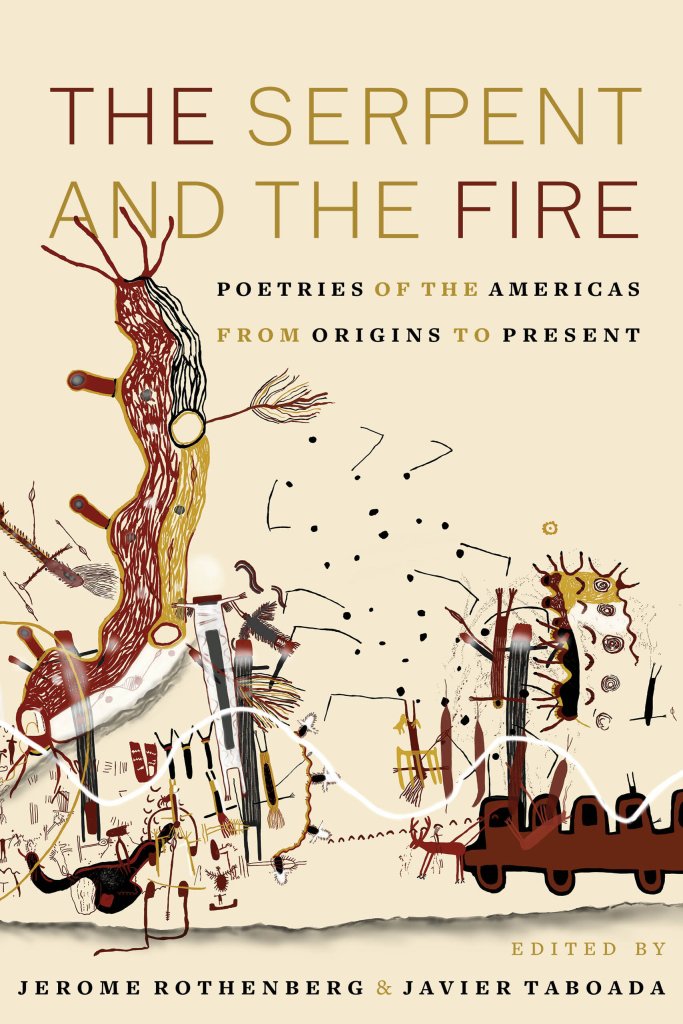

The Serpent and the Fire and Louis Riel

This month marks the publication of the final assemblage of Jerome Rothenberg (with co-editor Javier Taboada), The Fire and the Serpent.

As the publisher’s website tells us:

Jerome Rothenberg’s final anthology—an experiment in omnipoetics with Javier Taboada—reaches into the deepest origins of the Americas, north and south, to redefine America and its poetries.

The Serpent and the Fire breaks out of deeply entrenched models that limit “American” literature to work written in English within the present boundaries of the United States. Editors Jerome Rothenberg and Javier Taboada gather vital pieces from all parts of the Western Hemisphere and the breadth of European and Indigenous languages within: a unique range of cultures and languages going back several millennia, an experiment in what the editors call an American “omnipoetics.”

The Serpent and the Fire is divided into four chronological sections—from early pre-Columbian times to the immediately contemporary—and five thematic sections that move freely across languages and shifting geographical boundaries to underscore the complexities, conflicts, contradictions, and continuities of the poetry of the Americas. The book also boasts contextualizing commentaries to connect the poets and poems in dialogue across time and space.

Included in the volume’s vast spatiotemporal range are poems by bp Nichol and Nicole Brossard, along with a contribution by myself and Antoine Malette, translations of some sections of Louis Riel’s Massinahican. To whet your appetite, I invite you to sample that translation and some remarks about it, here.

And, as an added bonus, I invite you to save 30% when you purchase a copy of this book from the University of California Press website: just enter code EMAIL30 at check out. (Hopefully the cost of shipping and handling won’t negate the savings…).

A Metonymic Ideogram Concerning Poetic Attention

I’ve resisted writing the following, but a small flurry of persistent synchronicities insists otherwise.

It began with a Facebook discussion thread, prompted by a Canadian anglophone poet of my acquaintance. “Saw the list of this year’s Griffin judges. If we have a Canadian nominee other than Michael Ondaatje’s poetry collection A Year of Last Things I will be surprised.”

Around the same time, I happened on a remaindered copy of Hans Blumenbergs’s Work on Myth, and two poetry collections by Daniel Borzutzky (The Ecstasy of Capitulation and The Performance of Becoming Human) arrived, along with Jerome McGann’s The Point Is to Change It: Poetry and Criticism in the Continuing Present.

In the opening pages of McGann’s book “The Argument,” McGann observes “[Walter Benjamin and Gertrude Stein] both approach the history of poetry as an emergency of the present rather than as a legacy of past. The emergency appears as a poetic deficit in contemporary culture, where values of politics and morality are judged prima facie more important than aesthetic values.” Regardless of one’s knowledge or opinion of Benjamin or Stein, McGann’s invocation of “emergency” is provocative, to thought and otherwise.

Then, today, Norman Finkelstein’s Restless Messengers posted a three-part piece on Michael Boughn, a brief introduction by Miriam Nichols along with a review of his latest poetry book and a book of essays (by Finkelstein, required reading). Reviewing that poetry collection, The Book of Uncertain A Hyperbiographical User’s Manual (Book One), the reviewer, John Tritica, remarks “Michael Boughn does not write what Jack Spicer called one night stand poems, those shiny, reader-friendly, award-winning, readily consumable poems so prized by mainstream anthologies and awards institutions.”

Readers with an ideogrammic/metonymic sense will surmise what I’m on about here. I’ll let this juxtaposition speak for itself…

“Hell’s Printing House”: Seventh Column (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Saturday 22 September 2001 The Globe and Mail published an essay article by John Barber “Wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains” (F4). Despite its critical stance toward the then-impending invasion of Afghanistan by coalition forces, the terms of its discourse were so pedestrian my frustrated and bored eye wandered across its six columns. The article read thus, against the grain, appeared oracularly clear, and the experience of that reading what I wanted to communicate in the resulting poem. The sense this reading made to me leaves its trace in minor editorialisations (where the text has been stepped on). This vision into the essence of our imagination of Afghanistan is as forbidding as the country itself: a land of glacierous and desert mountains and sandstorms and tire-melting heat that swallows whole armies. “Cut the word lines and the future leaks through.” Here, English speaks this vision: in dead or obscure words, new compounds and coinages. Syntactically, at root (or so Norman O. Brown told John Cage) the arrangement of Alexander’s soldiers in a phalanx (the Great, too, stopped in Afghanistan), the language has been demilitarized.

Soon after I had composed the poem and printed and bound it in chapbook form, The Capilano Review called for submissions for a special issue “grief / war / poetics” that responded to the then-recent 9/11 attacks. It kindly accepted “Seventh Column,” just not the whole thing, so I had to decide how to excerpt a poem that, despite its disruptive, disrupted syntax, was still, arguably, a “whole.” I opted to have TCR print the first eight and last six stanzas to create a manner of sonnet. That excerpt can be read here, a reading of which I share, below.

“Seventh Column” is, to my mind, a high water mark of my poetic practice, the most carefully, rigorously composed of any of my poems. The lineation and punctuation intentionally follow no consistent rule (some lines are end-stopped, others enjambed, some sentences begin with capitals and end with periods, others not…); words are sometimes broken into their syllables, resulting in new coinages or echoes of an older English (whose meanings are footnoted). The language is thus “made new” and impossible to dominate or domesticate by a hermeneutic will-to-meaning lacking sufficient Negative Capability. Indeed, the poem eluded even my own compositional rigor, somehow making itself circular, ending with the suffix ne- and beginning with the root -glected…

Next month: Luffere & Oþere

“Hell’s Printing House”: X Ore Assays (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

In 1998, I published my first trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems, which collected most of the poems in my previous chapbooks, other than those in On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (which can be accessed here under the ‘Orthoteny‘ tag). I continued to mine and open new compositional veins in line with what I had written, but embarked in a totally different direction in late 2001 with X Ore Assays, which takes inspiration from a number of sources. The most immediate is FEHHLEHHE (Magyar Műhely, 2001) by the Hungarian musician, archivist, editor, writer, and cultural worker Zsolt Sőrés. FEHHLEHHE deploys a wide, wild range of linguistic disruption: disjunctive syntax, polyglottism, collage, sampling, homophony, and portmanteau words, among other means. X Ore Assays is in part an attempt to engage Sőrés’ text in kind, wrighting an English that would imaginably answer his Hungarian. A more remote but profounder influence is the homophonic style that myself and the late Dan Philip Brack (DPB) corresponded in, portions of which were intergrated into his series of short prose works, Letters from Jenny. In our correspondence, very few words were spelled in anything other than a pun, a delirious, funny, private literature, a practice whose linguistic energy I desired to tap in composing the project whose working title came to be X Ore Assays. An even deeper inspiration was the surreal practice of William Burroughs in writing “the word hoard” that was reworked and worked up into his breakthrough novels Naked Lunch, Interzone, The Soft Machine, The Ticket that Exploded, and Nova Express. I aimed to cleave close as I could to that first definition of Surrealism: “Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation,” a much more fraught practice today than over two decades ago. The working title was motivated by this experiment: the texts, composed daily, would comprise a score (x-ore) of raw material (ore) to be assayed, measured, graded, and perhaps refined. However, a kind of ironic, poetic justice intervened. One of the days in this open-ended practice fell on September 11, inserting these texts radically and irretrievably in time’s flow. Curiously, that day was not immediately remarked; rather, hearing of, I think, Billy Collins’ refusal to write of the event almost a week later spurred, ultimately, fourteen more days of response, a supplemental sequence provisionally titled “Sewn Knot.”

That initial twenty, as a gesture of homage, I sent to Sőrés, who arranged to have them published in the Hungarian-language avant garde journal Magyar Műhely. “Sewn Knot” appeared, thanks to efforts of the editor-publisher of Broke magazine Andrea Strudensky, in the Canadian periodical dANDelion. “X Ore Assays” and “Sewn Knot” have presently been combined and are being revised and refined under the working title “after FEHHLEHHE,” which makes up the opening section of a manuscript-in-progress tentatively titled Fugue State.

The sections responding in real time to 9/11 were not among those included in the chapbook; they can, however, be read, here. I reproduce, below, a page from the middle of the book, and read the day’s work beginning “Wit noose Airecebo..”

Next month: Seventh Column (2001).

Resist, much?

It was and remains an aesthetic, critical, compositional commonplace in some circles that the poem that resists ready understanding resists the capitalist order that would reduce all things to readily consumable commodities.

There are, of course, at least caveats to this position. No text, however transparent, is ever absolutely so, or it would be invisible. That is, all language is possessed of an aesthetic aspect (phonic, graphic, or tactile) as a condition of its possibly serving as a communicative or aesthetic medium at all; its materiality is inescapable. Moreover, no poem can possibly give over its reserves of meaning. “The words on the page” (to invoke a hoary critical paradigm), under sufficient scrutiny, betray an interpretive wealth far in excess of their immediate, prosaic, “literal” meaning. Even more, as a text, the poem is woven from and thereby back into other discourses; it is implicated in a very complex way in its culture. Furthermore, being a temporal phenomenon, that is, existing through time, this con-text will vary; being “fatherless,” the poem will be variously resituated, recontextualized, by ever new readers and thereby made to resonate in new, unforeseeable and uncontrollable ways. And one would be remiss to not remark most critically that it is not the poem that is, strictly, commodified, but what contains it, the book, periodical, or website; the poem is not consumed, per se, but the “thing” that packages it, which is bought and sold.

To these reflections, Abigail Williams’ Reading It Wrong: An Alternative History of Early Eighteenth-Century Literature seems to add a new angle. As the publisher’s description relates,

Focussing on the first half of the eighteenth century, the golden age of satire, Reading It Wrong tells how a combination of changing readerships and fantastically tricky literature created the perfect grounds for puzzlement and partial comprehension. Through the lens of a history of imperfect reading, we see that many of the period’s major works—by writers including Daniel Defoe, Eliza Haywood, Mary Wortley Montagu, Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift—both generated and depended upon widespread misreading. Being foxed by a satire, coded fiction or allegory was, like Wordle or the cryptic crossword, a form of entertainment…

Williams’ argument is compelling in at least two ways. First, her sample texts’ being resistant to understanding is precisely their appeal, their “selling point.” Second, the horizon of this elusive, allusive aesthetic is the early morning of capitalism in England, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, a famous index of the ideology of the moment. However, 2023 is not 1723, however much both are determined by a shared social formation, nor is the superstructure of these two moments the same. (Habermas’ forthcoming A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics is all the more looked forward to in this regard). Nevertheless, Williams’ study complicates the still vital, urgent demand to think about the place and function of poetic language in our present, critical moment….

AN OMNIPOETICS MANIFESTO, from PRE-FACE TO A HEMISPHERIC GATHERING OF THE POETRY & POETICS OF THE AMERICAS “FROM ORIGINS TO PRESENT”

I share here an excerpt from the Pre-face to Rothenberg’s and Taboada’s forthcoming assemblage of poetry and poetics from the Americas, from origins to the present. Not only is the omnipoetics manifesto therein of overriding interest in its own right, but Rothenberg’s and Taboada’s anthology also includes a translation from Louis Riel’s Massinahican by Antoine Malette and myself, some of which can be read, here.

The post, first published 4 October 2023, at Rothenberg’s Poems and Poetics blogspot can be read, here.

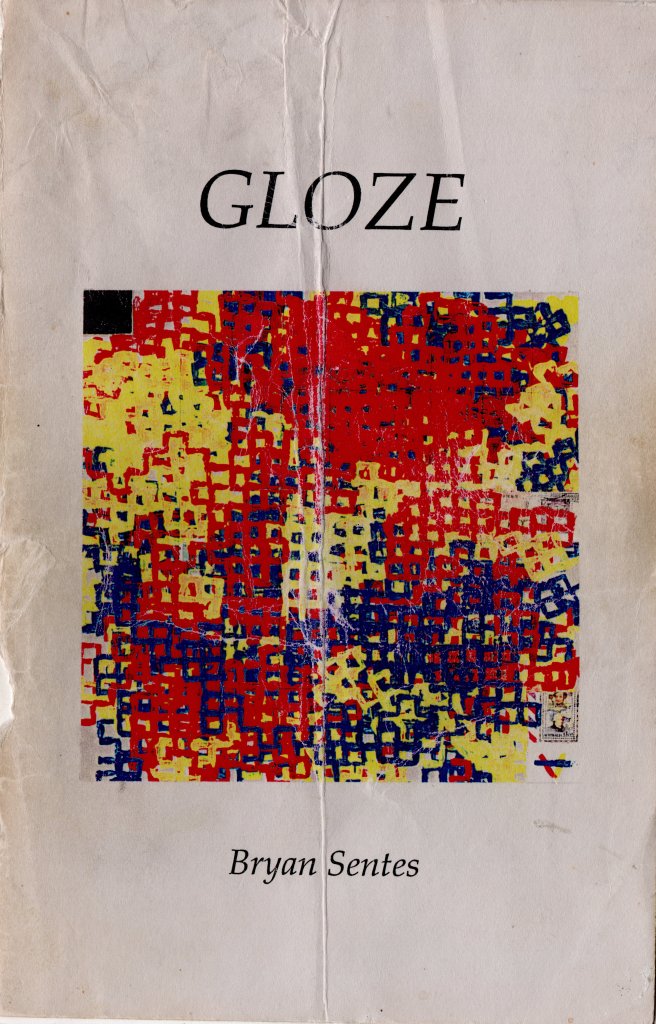

“Hell’s Printing House”—Gloze (1995)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Gloze is my first self-produced, self-published chapbook, inspired by Pneuma Press’ Budapest Suites. As I note in the prefatory remarks to this series of posts, Gloze and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery were the works that represented me during my European Tour of 1996 and for some years after, until the publication of my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central and other poems in 1998. The cover is an original artwork of my own, an aleatoric painting in acrylic and collage.

Contents

- Grand Gnostic Central

- After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort

- Smalltalk Hamburg 91

- Two

- Three

- In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14

- DP Channels Baba G

- Arachnophobia Prima Facie

- Five

- Thou, Palæmon

- Transcription

- Six

- “As I delighted with the enjoyments of torment…”

- Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli

- Otto (1)

- Á Québec

- ‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath

- Horizontal Gold Golden Mercury

- Tonight

- Green Wood

- Ten

- Marmitako

- Will of the Wisp

- Coda: Gloze

“Grand Gnostic Central” is, here, five prose poems (one of which can be read here) and the poem “Tonight, the world is simple and plain.” All poems hyperlinked above are “published” on Poeta Doctus; “Gloze” is represented by a YouTube rendition by “Jake the Dog.”

Although I had yet to publish a full-length trade edition, the poems collected in Gloze already gather work representative of a decade’s work and engagement with the poetry of my peers. At least the prose poem about Wittgenstein and the poem beginning “Tonight, the world is simple and plain…” along with that engaging Meister Eckhart (“After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort”) were composed during my graduate studies (1986-89), when I was labouring to write a way between and with poetry and philosophy, the topic of my master’s thesis. Nevertheless, my concerns were hardly exclusively abstruse: “Smalltake Hamburg 91″ addresses racism,”Thou, Palæmon” the first Gulf War, and “Á Québec” québecois nationalism. As down-to-earth, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury” and “Marmitako” ruminate on the alchemy and joy of preparing our daily bread. At the same time, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury,” with its allusion to alchemy and the Hermetic philosophy, betrays an interest in more recherché matters, whether the psychicomagical experimentation of Willliam Butler Yeats (“Otto (1)”) or ghost stories from my grandparents’ generation (“Will of the Wisp”), whose Hungarian side are given a nod in the poem “‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath,” no less a satire of, again, ethnonationalism. “DP Channels Baba G” is a terse condensation of the life of a Hindu saint, a gesture toward an attention to more “spiritual” matters, a leitmotif in much of my poetry. “Arachnophobia Prima Facie” is more psychological, exploring a fear of spiders that reaches back to my earliest memories. “In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14” is a humorous poem about poetic influence and stature.

But, apart from such thematic concerns, many of the poems are more overtly formal, compositional or artistic in their motivations. As I remark with regards to the poem “Six”:

Back in the early Nineties of last century (!) when I wrote this poem, the fashion among many Canadian (at least) poets was to write sonnet sequences. By chance, one day, I wrote a poem (“I know the Aurora Borealis” in Grand Gnostic Central) that happened to have fourteen lines. That chance (which to my ear happily rhymes with ‘chants’) occurrence began an ongoing, half-satirical series of accidentally-fourteen-line poems I called variously over the years “soughknots” (literally “air-knots”) and here “sonots” (so not sonnets!).

All the numbered poems are such sonots. Aside from the prose poem about Wittgenstein in “Grand Gnostic Central,” the others are inspired by early ‘pataphysical prose poems of Chris Dewdney’s. “Transcription” is a sequence of improvisations, likely motivated by an engagement with the spontaneous poetics of the Beats, which I had studied intensively during a memorable summer course in my graduate studies. “Tonight” pretends to this mode, but frees itself from it by means of a litotic irony turning on the ambiguity of a pronoun. “As I delighted with the enoyments of torment…,” “Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli,” and “Gloze” are all experiments in collage poetics. “Gloze,” especially, is a formal innovation of my own, prompted by the Wittgensteinian dictum that “meaning is use.” “Gloze,” and other poems, collate all the meanings of a word or phrase and represent them cubistically by means of the examples provided by the Oxford English Dictionary…

Of all the poems in Gloze, I’m most moved to share “Green Wood,” a poem that synthesizes much of the influences and experiments present in the book. On the face (and “ear” of it), it is reminiscent of the rhapsodic poetry of Allen Ginsberg and others. However, it’s opening line nods to a more radical influence, a translation from Lucretius by Basil Bunting. However much it might be said to deal with personal experience, it tends toward a more objective, metonymic, paratactical presentation, and is guided by a shy, mystical sensibility, perhaps most visible in its attention to synchronicities. Below, you can hear recordings of that poem, along with a performance of Bunting’s translation, a poem I was given to recite at the beginning of my poetry readings at the time.

“Green Wood”

Bunting’s Lucretius’ “Hymn to Venus”

Next month, X Ore Assays (1st Score), 2001:

Irritability is a sign of life…

IRRITABILITY: the property of protoplasm and of living organisms that permits them to react to stimuli.

Poet (and a quite respectable poet I might add) Ralph Kolewe shared the above passage and caption this Labour Day. That it irritated me is an understatement…

That opening paragraph, with its allusion to “the ‘outpouring of powerful emotion’ connected with the rise of Romantic poetry” will twig with those readers who remember a time in the not so distant past when, imaginably as a reaction to what was perceived to be a persistent, pernicious poetic, it was de rigueur to set up a Straw Man Wordsworth as responsible. Zwicky’s wording is brow-furrowing, for it suggests that either she has misremembered Wordsworth’s actual words from the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads (“For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings…”) or that she has formulated a parody of them to gesture toward that modern tendency she has in her sights, a tendency a faint echo of the Romantic thunderclap. Surely, the more charitable reading is the latter, but then the weakness of what she would negate infects her position: how strong can it be if it needs set itself over against a mere parody of its much more sophisticated and robust progenitor?

Just what poetic tendency, then, does Zwicky have in her sights? The answer to this question likely lies in the 301 other remarks and their parallel running text of quotations that compose Lyric Philosophy, the book Kolewe quotes. I must admit, scrutinizing the cited passage isn’t very helpful: this “corrupt” sense of lyric “emphasizes the rôle of the individual ego” in an “‘outpouring of powerful emotion’,” a sense “based” on a “celebration” rather than “relinquishment of the individual ego,” an emphasis and celebration that presumably results in “isolation” rather than “connection.” Some poetry from the past six or seven decades might come to mind, but the search leads away, ultimately, from the lyric sense Zwicky would affirm, and its own, not unproblematic Vorurteilen (prejudices or presuppostions…).

First, what sense of ego is operative here? Is it the Cartesian cogito, the transcendental subject of Kant or the “I am” that accompanies all thought, or the transcendental ego of Husserl, or the ego of psychoanalysis or analytic psychology? Is it some pedestrian understanding of the individual self, or even a particular inflection of the lyric “I,” that endlessly problematic persona? An answer may lie in the context of the work from which the remark is abstracted.

More gravely, however, the thinking here seems to overlook that longstanding “relinquishment of the individual ego” in modern and even “archaic” poetries. Certain strains of avant garde poetics, from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, to the chance generated poems of John Cage and Jackson MacLow, along with William Burrough’s “Third Mind” poetics, back to Charles Olson’s “objectism” (and his explicit criticism of the place of the ego in Ezra Pound’s Cantos), the practice of the Objectivists, or the impersonality advocated by the early Eliot, or even Yeat’s masks all questioned or sidestepped the primacy of that individual ego. One could extend this line back even to the “I” in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ernesto Cardenal’s exteriorismo and Pessoa’s (and Canada’s Erin Mouré’s) heteronyms come to mind. The poetics of French Surrealism and Mallarmé’s poetry or a particular reception of Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” are apropos. And what of that obscure “I” crystallized in autobiographical shibboleths in Celan’s later poetry? More radically, even a cursory reading of Jerome Rothenberg’s assemblage Technicians of the Sacred reveals a global range of poetries, communal, divinatory, shamanic, and otherwise that spring from sources and concerns other than “the individual ego.”

My point here is not to contradict Kolewe’s enthusiasm or set Zwicky up as a Straw Person, but rather to register a particular impatience with reflections on poetics that gaze into too shallow a small pool. Poetries that sing something other than an individual self are legion. All of which leaves aside for the moment the question of the grounds for and imaginable value of a lyric practice that dwells on and in an I, if not celebrates it. Perhaps blame lies with that first modern poet, Dante Alighieri, and his making at least three aspects of himself and their poetic and eternal fate the subject of his Commedia…

Leave a comment

Leave a comment