Archive for the ‘poetry’ Tag

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April 18, 19, 21, 24, and 26

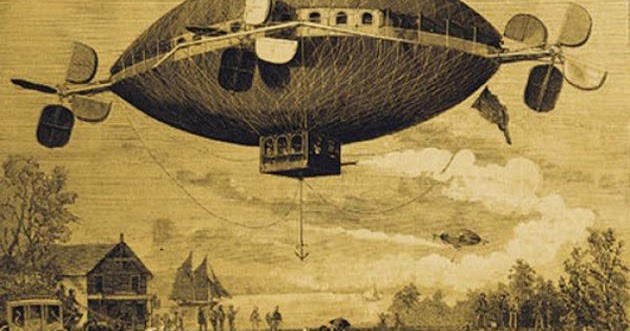

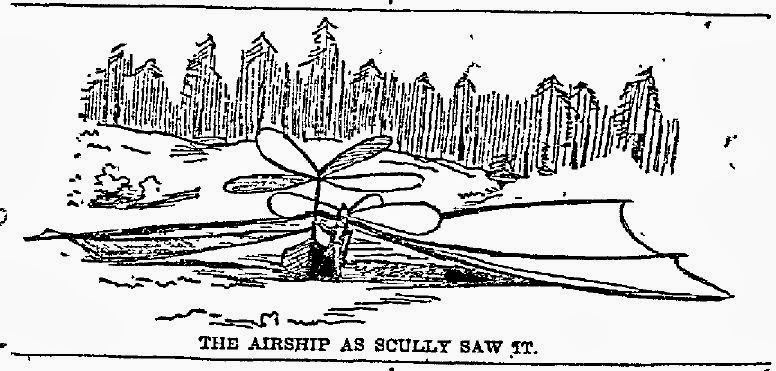

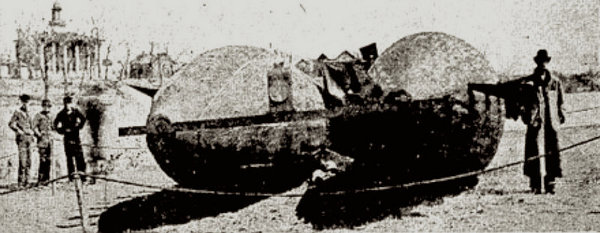

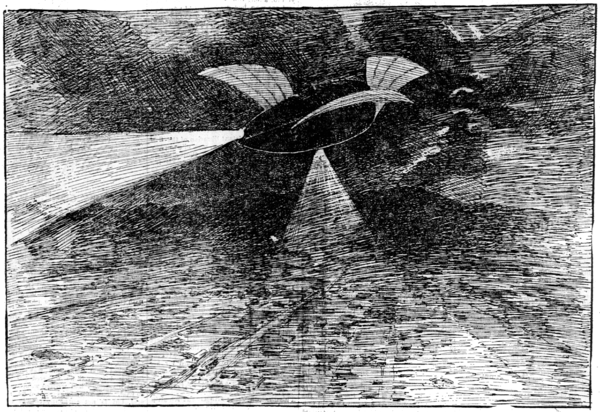

Here, the penultimate cantos from a section of a long work concerned with “the myth of things seen in the skies,” Orthoteny. These cantos relate phantom airship sightings, landings, meetings with their pilots, and debunkings from a prototypical UFO “wave” that occurred in April, 1897. These tales are of interest for including (among other things) the first report of a cattle mutilation and the story of an airship dragging an anchor, which echoes a tale from the Middle Ages!

You can read these poems, and hear them, too, here.

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April the 17th, Aurora

Here’s the next instalment from a part of a long poem Orthoteny dealing with “the myth of things seen in the sky,” an episode from the Mystery Airship wave of 1896/7, here an archetypal UFO crash. You can read it—and hear it!—here.

Resist, much?

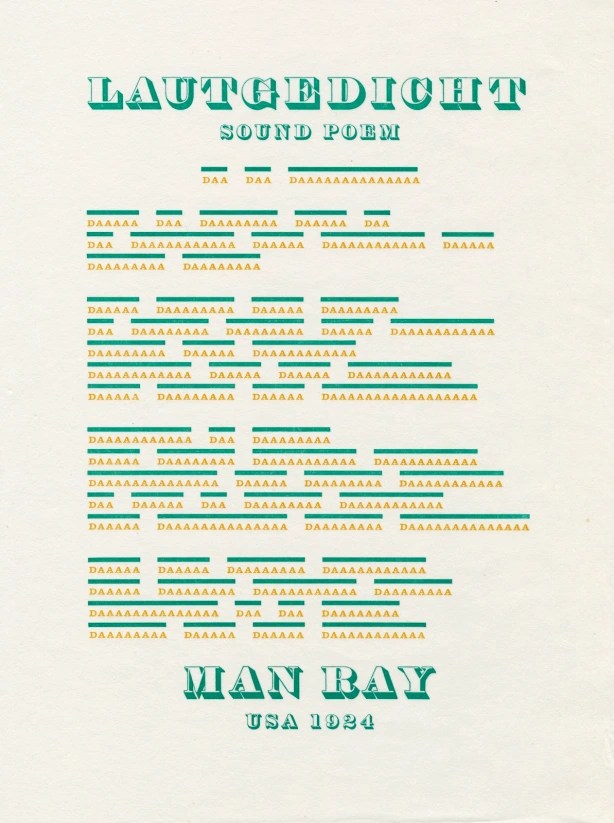

It was and remains an aesthetic, critical, compositional commonplace in some circles that the poem that resists ready understanding resists the capitalist order that would reduce all things to readily consumable commodities.

There are, of course, at least caveats to this position. No text, however transparent, is ever absolutely so, or it would be invisible. That is, all language is possessed of an aesthetic aspect (phonic, graphic, or tactile) as a condition of its possibly serving as a communicative or aesthetic medium at all; its materiality is inescapable. Moreover, no poem can possibly give over its reserves of meaning. “The words on the page” (to invoke a hoary critical paradigm), under sufficient scrutiny, betray an interpretive wealth far in excess of their immediate, prosaic, “literal” meaning. Even more, as a text, the poem is woven from and thereby back into other discourses; it is implicated in a very complex way in its culture. Furthermore, being a temporal phenomenon, that is, existing through time, this con-text will vary; being “fatherless,” the poem will be variously resituated, recontextualized, by ever new readers and thereby made to resonate in new, unforeseeable and uncontrollable ways. And one would be remiss to not remark most critically that it is not the poem that is, strictly, commodified, but what contains it, the book, periodical, or website; the poem is not consumed, per se, but the “thing” that packages it, which is bought and sold.

To these reflections, Abigail Williams’ Reading It Wrong: An Alternative History of Early Eighteenth-Century Literature seems to add a new angle. As the publisher’s description relates,

Focussing on the first half of the eighteenth century, the golden age of satire, Reading It Wrong tells how a combination of changing readerships and fantastically tricky literature created the perfect grounds for puzzlement and partial comprehension. Through the lens of a history of imperfect reading, we see that many of the period’s major works—by writers including Daniel Defoe, Eliza Haywood, Mary Wortley Montagu, Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift—both generated and depended upon widespread misreading. Being foxed by a satire, coded fiction or allegory was, like Wordle or the cryptic crossword, a form of entertainment…

Williams’ argument is compelling in at least two ways. First, her sample texts’ being resistant to understanding is precisely their appeal, their “selling point.” Second, the horizon of this elusive, allusive aesthetic is the early morning of capitalism in England, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, a famous index of the ideology of the moment. However, 2023 is not 1723, however much both are determined by a shared social formation, nor is the superstructure of these two moments the same. (Habermas’ forthcoming A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics is all the more looked forward to in this regard). Nevertheless, Williams’ study complicates the still vital, urgent demand to think about the place and function of poetic language in our present, critical moment….

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, April 12-16

Here, the next instalment of ten cantos more from a poem about an archetypal moment from that “myth of things seen in the skies,” a prototypical “UFO flap” from April, 1897, again, with a newly-made recording…

“Hell’s Printing House”—Gloze (1995)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

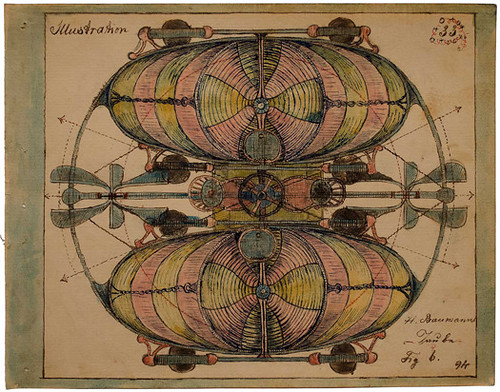

Gloze is my first self-produced, self-published chapbook, inspired by Pneuma Press’ Budapest Suites. As I note in the prefatory remarks to this series of posts, Gloze and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery were the works that represented me during my European Tour of 1996 and for some years after, until the publication of my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central and other poems in 1998. The cover is an original artwork of my own, an aleatoric painting in acrylic and collage.

Contents

- Grand Gnostic Central

- After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort

- Smalltalk Hamburg 91

- Two

- Three

- In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14

- DP Channels Baba G

- Arachnophobia Prima Facie

- Five

- Thou, Palæmon

- Transcription

- Six

- “As I delighted with the enjoyments of torment…”

- Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli

- Otto (1)

- Á Québec

- ‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath

- Horizontal Gold Golden Mercury

- Tonight

- Green Wood

- Ten

- Marmitako

- Will of the Wisp

- Coda: Gloze

“Grand Gnostic Central” is, here, five prose poems (one of which can be read here) and the poem “Tonight, the world is simple and plain.” All poems hyperlinked above are “published” on Poeta Doctus; “Gloze” is represented by a YouTube rendition by “Jake the Dog.”

Although I had yet to publish a full-length trade edition, the poems collected in Gloze already gather work representative of a decade’s work and engagement with the poetry of my peers. At least the prose poem about Wittgenstein and the poem beginning “Tonight, the world is simple and plain…” along with that engaging Meister Eckhart (“After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort”) were composed during my graduate studies (1986-89), when I was labouring to write a way between and with poetry and philosophy, the topic of my master’s thesis. Nevertheless, my concerns were hardly exclusively abstruse: “Smalltake Hamburg 91″ addresses racism,”Thou, Palæmon” the first Gulf War, and “Á Québec” québecois nationalism. As down-to-earth, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury” and “Marmitako” ruminate on the alchemy and joy of preparing our daily bread. At the same time, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury,” with its allusion to alchemy and the Hermetic philosophy, betrays an interest in more recherché matters, whether the psychicomagical experimentation of Willliam Butler Yeats (“Otto (1)”) or ghost stories from my grandparents’ generation (“Will of the Wisp”), whose Hungarian side are given a nod in the poem “‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath,” no less a satire of, again, ethnonationalism. “DP Channels Baba G” is a terse condensation of the life of a Hindu saint, a gesture toward an attention to more “spiritual” matters, a leitmotif in much of my poetry. “Arachnophobia Prima Facie” is more psychological, exploring a fear of spiders that reaches back to my earliest memories. “In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14” is a humorous poem about poetic influence and stature.

But, apart from such thematic concerns, many of the poems are more overtly formal, compositional or artistic in their motivations. As I remark with regards to the poem “Six”:

Back in the early Nineties of last century (!) when I wrote this poem, the fashion among many Canadian (at least) poets was to write sonnet sequences. By chance, one day, I wrote a poem (“I know the Aurora Borealis” in Grand Gnostic Central) that happened to have fourteen lines. That chance (which to my ear happily rhymes with ‘chants’) occurrence began an ongoing, half-satirical series of accidentally-fourteen-line poems I called variously over the years “soughknots” (literally “air-knots”) and here “sonots” (so not sonnets!).

All the numbered poems are such sonots. Aside from the prose poem about Wittgenstein in “Grand Gnostic Central,” the others are inspired by early ‘pataphysical prose poems of Chris Dewdney’s. “Transcription” is a sequence of improvisations, likely motivated by an engagement with the spontaneous poetics of the Beats, which I had studied intensively during a memorable summer course in my graduate studies. “Tonight” pretends to this mode, but frees itself from it by means of a litotic irony turning on the ambiguity of a pronoun. “As I delighted with the enoyments of torment…,” “Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli,” and “Gloze” are all experiments in collage poetics. “Gloze,” especially, is a formal innovation of my own, prompted by the Wittgensteinian dictum that “meaning is use.” “Gloze,” and other poems, collate all the meanings of a word or phrase and represent them cubistically by means of the examples provided by the Oxford English Dictionary…

Of all the poems in Gloze, I’m most moved to share “Green Wood,” a poem that synthesizes much of the influences and experiments present in the book. On the face (and “ear” of it), it is reminiscent of the rhapsodic poetry of Allen Ginsberg and others. However, it’s opening line nods to a more radical influence, a translation from Lucretius by Basil Bunting. However much it might be said to deal with personal experience, it tends toward a more objective, metonymic, paratactical presentation, and is guided by a shy, mystical sensibility, perhaps most visible in its attention to synchronicities. Below, you can hear recordings of that poem, along with a performance of Bunting’s translation, a poem I was given to recite at the beginning of my poetry readings at the time.

“Green Wood”

Bunting’s Lucretius’ “Hymn to Venus”

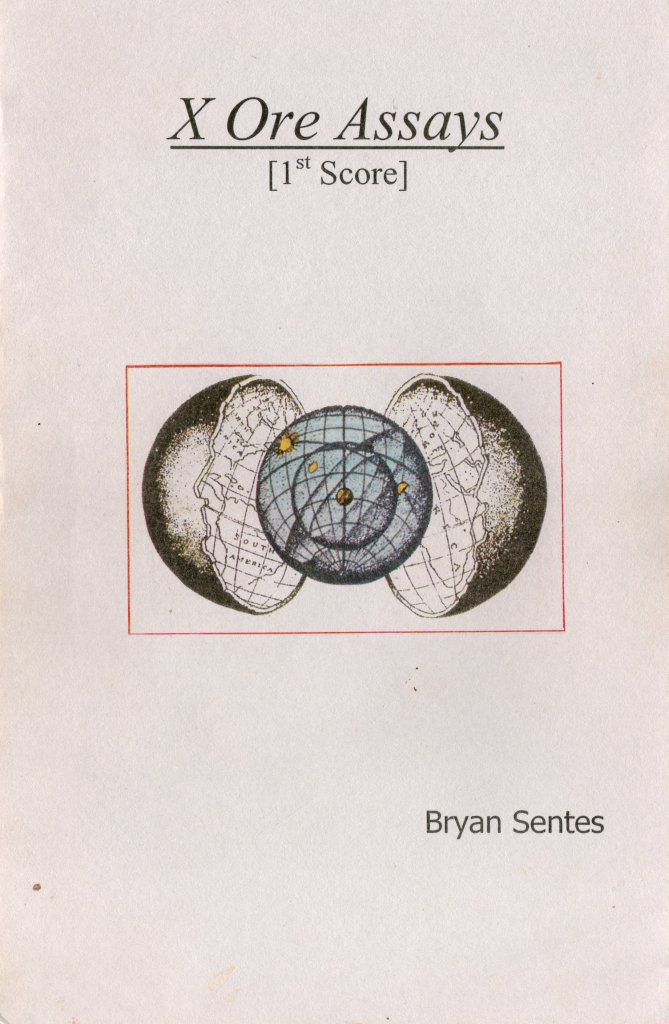

Next month, X Ore Assays (1st Score), 2001:

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April, 1, 2, 9, and 11

Here, the next instalment from my long poem probing the “myth of things seen in the skies,” the opening cantos from the most important section from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, “April,” complete with recording!

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: “The Phantom Air Ship”

I share here the latest instalment over at Skunkworksblog of part of a long, work-in-progress, a poetic treatment of the “myth of things seen in the skies.” This latest post is another part of the chapbook On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery that treats a prototypical “UFO wave” avant le lettre during the years 1896/7. You can read—and hear it!—here.

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, Prelude

Here’s the next instalment of the epic work-in-progress about the “myth of things seen in the skies.” This week, the Prelude to the most complete part of the project, a poetic recounting of an archetypal “UFO flap” over mainly the continental U.S. in 1896/7. You can read—and hear it!—here.

Cross post: from Orthoteny, a work in progress…

Apart from what goes on here at Poeta Doctus, there’s a whole other side to my poetic, cultural work, I reveal only to a select readership. There, for longer than I care to admit, I’ve been labouring on a long work on what Carl Jung termed “a modern myth of things seen in the sky.”

I’ll be posting parts of that epic-in-process, whose working title is Orthoteny, along with a recording of a new reading of that part, weekly, for the foreseeable future.

You can read the first post in this new series, here.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment