Absolutely modern Romanticism

Welcome news from Jerome Rothenberg concerning a new initiative by Jeffrey C. Robinson, with whom he edited an essential assemblage Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: Romantic and Postromantic poetry.

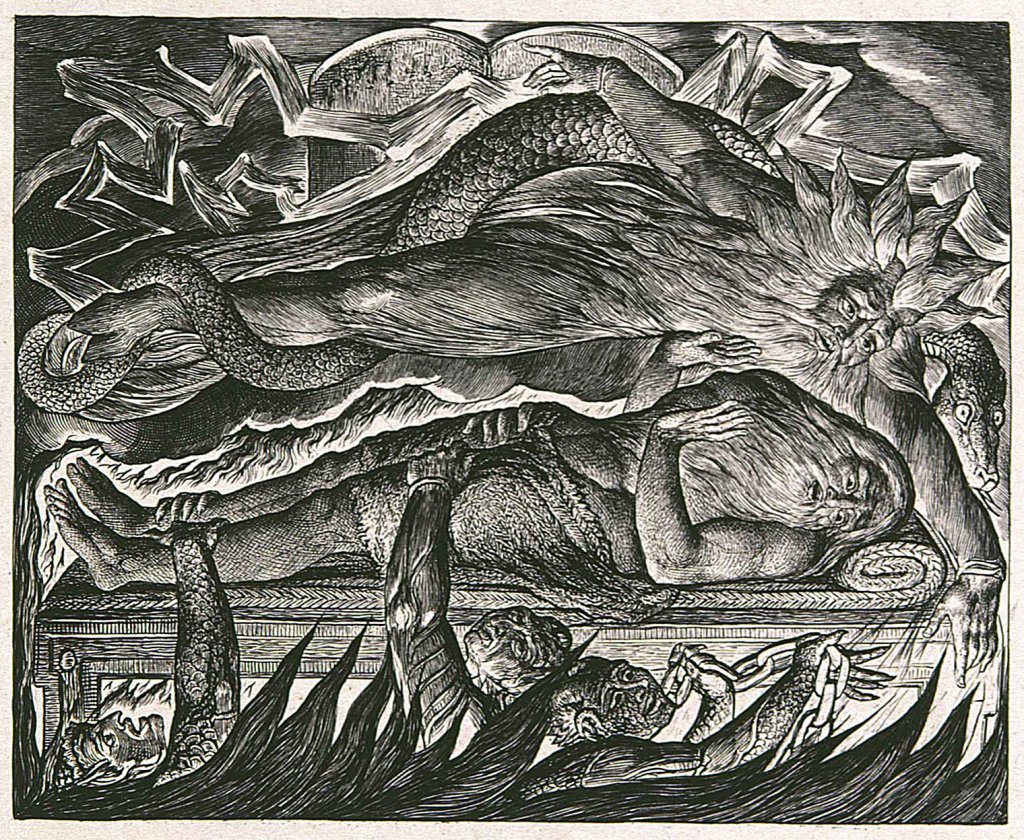

Announced is a putative collection of “75 or so statements, terms, and jargon from the ‘Romantic mother-lode’ (Anne Waldman) with the hope that together, with accompanying commentary, they will accumulate irrefutably a major well-spring for modern and contemporary innovative poetry,” a collection that will prompt a “recognition of [romantic poetics] as a loose system of outlandish thought for the renovation of poetry in the service of a renovation of society.” Robinson highlights a handful of salient concerns (in his words): a new view of the world, sub specie aeternitatis; the not unrelated symbolic implications of Jacob’s Dream; the Fragment as Coherence over Unity and the Future; and a stance Against “palpable design”.

Romanticism, as a sensibility, but always too-much anchored to a concept of its being an historical period, has been resurgent, at least, since the reaction to the strictures of (at least, anglophone) literary Modernism (e.g., the criticism of T. E. Hulme, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) and the (ideological) aesthetic of the New Criticism. The poetics at work in the poetry of Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg and in the criticism of Harold Bloom, Geoffrey Hartman, and Paul de Man are well-known examples of this countermovement. However, first, with the scholary innovation of “constellation studies” and the resultant, rigorous reappraisal of Jena Romanticism and German Idealism (here, the names Dieter Henrich, Manfred Frank, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Andrew Bowie are exemplary) through the 1970s and 1990s served (at least among those paying attention) to utterly reorient the place and value of the thinking called “Theory” and the poetics and compositional practice that Theory influenced. Into this context, though with their own perspective on the matter and what’s at stake, step Rothenberg and Robinson with the above-mentioned assemblage (2009), the accompanying volume of poetics Active Romanticism (eds. Julie Carr and Jeffrey C. Robinson, 2015), and Robinson’s just announced project.

However much my own thoughts (and practice) are more or less in harmony with Robinson’s, there are points both of disagreement and concurrence. Coming of intellectual age studying Existentialism and Phenomenology (which, like Sartre, has led to an engagement with Historical Materialism) I’m leery of the invocation of the Spinozistic idea of viewing the world (and human life (and history)) sub specie aeternitatis (though, admittedly, Robinson does spin this notion in his own way). My aesthetic is very much, as I say, “ontological”, attending to what is given as the primary material, a nonjudgemental sensibility as phenomenological, Objectivist, “mindful”, or—as our romantic forbears (and descendants) put it, “prophetic” or “vatic”, an aesthetic that might well be said to be, in Robinson’s words, “forgiving.” In as much as such a stance is variously “estranging”, a literary value articulated by Novalis and Coleridge well in advance of Shklovsky, I am, again, in agreement. More philosophically (if not fundamentally), the view Robinson espouses here is in line with various posthumanist philosophical movements, such as Object Oriented Ontology (despite its antiKantian stance) and Timothy Morton’s not-unrelated Dark Ecology, the renewed interest in psychedelics, and other attempts to re-enchant the world, such as those of scholars Jeffrey Kripal, Jason Ãnanda Josephson Storm, and Marshall Sahlins, currents that pique my curiosity but no less my skepticism.

Robinson’s invocation of the fragment is welcome; my own poetics orbits the metonymical, which is essentially fragmental, in the Romantic sense. I find the futurity of the fragment demands more brow-furrowing; the optimism of writing for the future must, as, for example, much of the early writing of the Beat Generation did under the shadow of nuclear annihilation, be tempered by the very real possibility of cultural-historical foreclosure, the anxiety that has moved many young people from reproducing in the face of the threats of climate change…

What I find of most promise in Robinson’s proposals is his invocation of a poetics that eschews a “palpable design” (“We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us,” in Keats’ words). This approval might seem jarring in light of my invocation of the climate crisis and my admitted Historical Materialist sympathies, but anyone who has read, for example, Adorno’s essay on the drama of Sartre and Brecht “Commitment” will have a better idea of a writing without “palpable design.” Robinson invokes Vicente Huidbro, the Chilean poet of Altazor, “who locates palpable design as an intrusion of the ‘horribly official stamp of approval of a prior judgment (perhaps of long standing) at the moment of production’.” As Robinson glosses Huidbro:

Palpable design, while it may have been internalized, comes from without, from the social and cultural spheres, from “custom,” from the panopticon, from a voracious market economy with its association of any product, including a poem, with its acquisition, and from gender, race, and class inequities; it appears in poetry as received forms and received modes of speech that produces the familiar and consoling.

Here, Robinson’s writing of the fragment as a “pro-ject” invokes vital aspects of Olson’s Projective Verse as much as Nicanor Parra’s “anti-poetry” and the creative spirit and attendant strange novelty (creation) that runs from Dante, Cervantes, and Shakespeare (the Holy Trinity of the Jena Romantics) down to today. What is demanded by unprecendented times is an unprecendented poetry. Indeed, we live on a planet never inhabited by Homo Sapiens. What more radical call to make it new could be sounded?

Wonderful, Love—