Archive for September, 2023|Monthly archive page

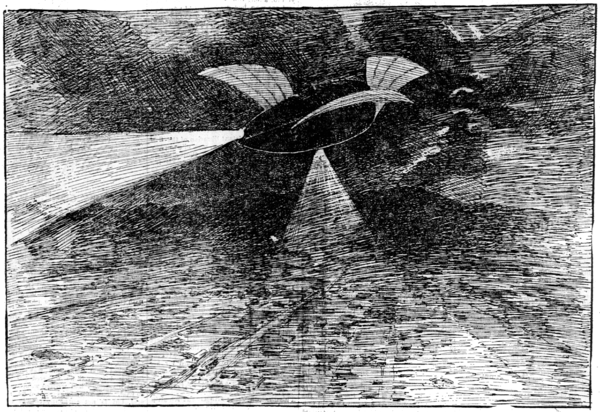

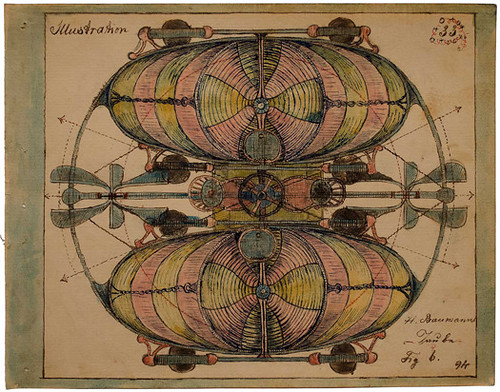

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: “The Phantom Air Ship”

I share here the latest instalment over at Skunkworksblog of part of a long, work-in-progress, a poetic treatment of the “myth of things seen in the skies.” This latest post is another part of the chapbook On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery that treats a prototypical “UFO wave” avant le lettre during the years 1896/7. You can read—and hear it!—here.

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, Prelude

Here’s the next instalment of the epic work-in-progress about the “myth of things seen in the skies.” This week, the Prelude to the most complete part of the project, a poetic recounting of an archetypal “UFO flap” over mainly the continental U.S. in 1896/7. You can read—and hear it!—here.

Cross post: from Orthoteny, a work in progress…

Apart from what goes on here at Poeta Doctus, there’s a whole other side to my poetic, cultural work, I reveal only to a select readership. There, for longer than I care to admit, I’ve been labouring on a long work on what Carl Jung termed “a modern myth of things seen in the sky.”

I’ll be posting parts of that epic-in-process, whose working title is Orthoteny, along with a recording of a new reading of that part, weekly, for the foreseeable future.

You can read the first post in this new series, here.

Irritability is a sign of life…

IRRITABILITY: the property of protoplasm and of living organisms that permits them to react to stimuli.

Poet (and a quite respectable poet I might add) Ralph Kolewe shared the above passage and caption this Labour Day. That it irritated me is an understatement…

That opening paragraph, with its allusion to “the ‘outpouring of powerful emotion’ connected with the rise of Romantic poetry” will twig with those readers who remember a time in the not so distant past when, imaginably as a reaction to what was perceived to be a persistent, pernicious poetic, it was de rigueur to set up a Straw Man Wordsworth as responsible. Zwicky’s wording is brow-furrowing, for it suggests that either she has misremembered Wordsworth’s actual words from the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads (“For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings…”) or that she has formulated a parody of them to gesture toward that modern tendency she has in her sights, a tendency a faint echo of the Romantic thunderclap. Surely, the more charitable reading is the latter, but then the weakness of what she would negate infects her position: how strong can it be if it needs set itself over against a mere parody of its much more sophisticated and robust progenitor?

Just what poetic tendency, then, does Zwicky have in her sights? The answer to this question likely lies in the 301 other remarks and their parallel running text of quotations that compose Lyric Philosophy, the book Kolewe quotes. I must admit, scrutinizing the cited passage isn’t very helpful: this “corrupt” sense of lyric “emphasizes the rôle of the individual ego” in an “‘outpouring of powerful emotion’,” a sense “based” on a “celebration” rather than “relinquishment of the individual ego,” an emphasis and celebration that presumably results in “isolation” rather than “connection.” Some poetry from the past six or seven decades might come to mind, but the search leads away, ultimately, from the lyric sense Zwicky would affirm, and its own, not unproblematic Vorurteilen (prejudices or presuppostions…).

First, what sense of ego is operative here? Is it the Cartesian cogito, the transcendental subject of Kant or the “I am” that accompanies all thought, or the transcendental ego of Husserl, or the ego of psychoanalysis or analytic psychology? Is it some pedestrian understanding of the individual self, or even a particular inflection of the lyric “I,” that endlessly problematic persona? An answer may lie in the context of the work from which the remark is abstracted.

More gravely, however, the thinking here seems to overlook that longstanding “relinquishment of the individual ego” in modern and even “archaic” poetries. Certain strains of avant garde poetics, from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, to the chance generated poems of John Cage and Jackson MacLow, along with William Burrough’s “Third Mind” poetics, back to Charles Olson’s “objectism” (and his explicit criticism of the place of the ego in Ezra Pound’s Cantos), the practice of the Objectivists, or the impersonality advocated by the early Eliot, or even Yeat’s masks all questioned or sidestepped the primacy of that individual ego. One could extend this line back even to the “I” in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ernesto Cardenal’s exteriorismo and Pessoa’s (and Canada’s Erin Mouré’s) heteronyms come to mind. The poetics of French Surrealism and Mallarmé’s poetry or a particular reception of Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” are apropos. And what of that obscure “I” crystallized in autobiographical shibboleths in Celan’s later poetry? More radically, even a cursory reading of Jerome Rothenberg’s assemblage Technicians of the Sacred reveals a global range of poetries, communal, divinatory, shamanic, and otherwise that spring from sources and concerns other than “the individual ego.”

My point here is not to contradict Kolewe’s enthusiasm or set Zwicky up as a Straw Person, but rather to register a particular impatience with reflections on poetics that gaze into too shallow a small pool. Poetries that sing something other than an individual self are legion. All of which leaves aside for the moment the question of the grounds for and imaginable value of a lyric practice that dwells on and in an I, if not celebrates it. Perhaps blame lies with that first modern poet, Dante Alighieri, and his making at least three aspects of himself and their poetic and eternal fate the subject of his Commedia…

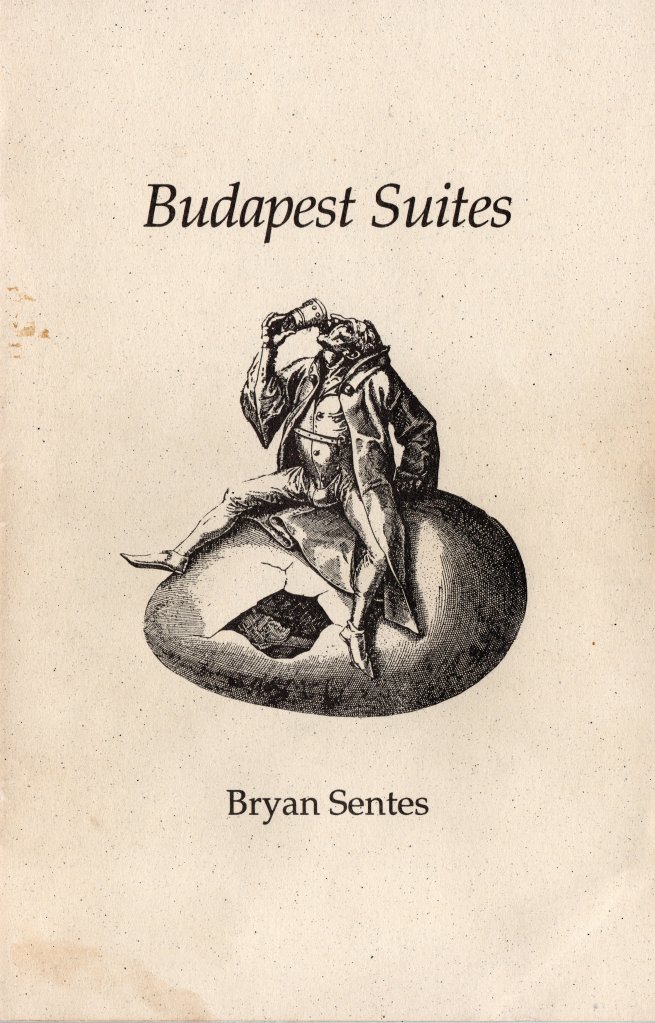

“Hell’s Printing House”—Budapest Suites (1994)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Budapest Suites is the first published version of the titular poetic suite that later appeared, slightly revised, in my first, full-length trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems (1998). It, along with all books issued in the Pneuma Poetry Series, was designed and printed by my friend Richard Weintrager.

Contents

- “Apply what you know to what you feel that’s more than enough”

- “Mount Ság”

- “That he might…”

- “The chest-high white-haired Swiss woman asked…”

- “I went down to Bibliomanie”

- “Dan and I waltzed hopfrog…”

- “You don’t just follow an impulse do you?”

Budapest Suites collects poems written during and after a 1991 trip to Europe (my first!), whose highpoint was a visit to Budapest and Celldömölk, the hometown of scholar poet friend Kemenes Géfin László, there to be honoured for his literary work and to launch his avant garde epic work Fehérlófia (the son of the white horse). On that occasion, we visited the extinct volcano on the outskirts of town Mount Ság (Sághegy) where Géfin had hidden out during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 before escaping over the border to Austria. Géfin was struck by the lushness of the locale, so much he was moved to remark, “There is a god here!”, the opening line of the second suite.

In Budapest, I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of some American ex-pats, among them, writer Dan Philip Brack (DPB), “Dan” in the opening line of the penultimate suite. Let’s attribute the epigraphs of the first and last suites to him. The fourth suite commemorates a visit to the National Museum. The third suite, as well, was written in situ. The fourth suite was composed after returning to Montreal; its being slightly confusing might be attributable to its being “a mystical poem,” as Hungarian poet Tibor Zalán called it.

The poem recorded below is the third suite. Darius Snieckus, author of the inaugural chapbook in the Pneuma Poetry Series, The Brueghel Desk, was so impressed when he read it, he insisted I not “change a thing!”. His anxieties were not unfounded, as up to and into the writing of the Suites, I had been an obsessive reviser: I still have the notebook with the seventeen (at least) versions of “Mount Ság” worked over that one afternoon, including the Hungarian translation by Zalán and András Sándor, which was read to Géfin on site in honour of the visit.

It was in revising the fourth suite that the most recent, nth version turned out to be identical to the very first. It was then I learned the truth of William Blake’s dictum “First thought best in Art…” From that revelation on, my compositional practice was to write, then carefully study what had been written to understand its spontaneous rightness before cautiously making slight alterations, only in order to bring out the energy of that original impulse all the better. It was Joachim Utz, one my most careful German readers, who noted that the Budapest Suites marked a “breakthrough” in my poetry.

Next month, Gloze (1995)…

Announcing “Hell’s Printing House”

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

First up, Budapest Suites (Pneuma Poetry Series, 1994)…

“statements, terms, and jargon”: Saturday 2 September 2023

Time constraints and temperament restrict many of my thoughts to remarks. Thus, what follows are emphatically fragments, metonymies (parts) of potentially more-extended discourses and drafts (essays) holding the promise of future elaboration….

“If you want to change your life / burn down your house…” These words, which open Peter Dale Scott’s Minding the Darkness: A Poem for the Year 2000, strike an uncannily, untimely note in light of this season’s fires in Maui and in Canada’s north and west coast. The first canto of Scott’s long poem describes experiencing one of the no-less devastating wildfires Californians suffered in the closing years of last century. Both the fires in California and Maui left “rivulets of metal // from… melted cars.” From a broader, historical perspective, my German father-in-law, who came of age in the closing years of the Second World War in Germany’s industrial zone, the Ruhrgebeit, when he saw pictures of the devastation in Maui, was reminded of similar pictures he’d seen of a bombed-out Dresden. Such devastation, that stretches back, too, to that of the Great War, prompts Scott to cite Heidegger’s 1929 study, Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, concerning “Dasein face to face // with its original nakedness.” Have we here, perhaps, a new literary topos?…

Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, do not write but, more exactly, perhaps, merely generate not even intertext but a permutation of its elements (words). Where intertext, rigorously, is “scraps of text that have existed or exist…the texts of the previous or surrounding culture… a new tissue of past citations…”, the “wake of the already-written”, what LLMs produce is only the most probable order of words. Do such prototexts not, imaginably (if not imaginatively) call forth, then, from poetry a countermeasure, the demand to compose in the least likely syntax? This demand transcends The New Sentence, wherein parataxis occurs only between sentences, urging a rereading of not only those most syntactically centripetal L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poems, for example, but those explorations in this direction in, among others, the novels and poems of William Burroughs and John Cage, let alone those even older, deeper efforts to evade, avoid, or otherwise complicate the declarative sentence as “a complete(d) thought” in the poetry of Charles Olson, Ezra Pound, and William Carlos Williams, among so many others.

Or, from a related angle, chatbot “poems” need be considered in light of earlier modes of aleatoric composition, whether Burroughs’ Third Mind techniques or Cage’s or MacLow’s employment of the I Ching, or, farther back, Surrealism and Dada, or, even more radically, the various forms of divination throughout space and time, such as those collected in Jerome Rothenberg’s Technicians of the Sacred and remembered even in the classical heritage of antiquity (the Sybil’s leaves…). Given that the unconscious if not the “mindless” has been overtly and consciously employed in the composition of poetry to a variety of ends, chatbot “poems” or their precursors (which go back decades) are hardly “new.” Indeed, their very place in so-called “Late” Capitalism urges their scrutiny in light of the tradition, especially when they are employed “to write” “poems.” Is it inconsequential that Breton was a communist, that MacLow and, in his own way, Cage were anarchists?…

Perry Anderson, in his Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, sketches the grounds for “The General Crisis” of the Fourteenth Century. On the one hand, agricultural production reached a limit: existing, arable land was becoming degraded, and land that could be reclaimed had been and was of a poor quality. At the same time, silver mining could neither dig deeper nor exploit the relatively poor-quality ore that could be accessed, affecting the amount of coin in circulation. This crisis in the forces of production was aggravated by the Black Death, which killed an estimated net 40% of the population of Europe.

Parallels to our present day are suggestive. The carrying capacity of the earth’s ecology has been breached (however much we do in fact produce enough food to feed the world’s population; the problem is one of distribution), and we cannot in principle exploit existing fossil fuel reserves without burning down our own house. Covid is hardly the Black Plague, but it is only one of the pathogens that have been and will be released by the progressing economic colonialization of what wilderness remains.

Nevertheless, on the other side of the Fourteenth Century and its crises was not total collapse, but the Renaissance….

At a time of deep social fragmentation (Identity politics, ethnonationalisms…) and irrationality (a loss of consensus, determined by so many factors…) and no less in the face of the climate and more general environmental crisis is it not necessary, then, to revive the Universal and the Human?…

“To praise, that’s the thing!”

“Being a poet,” at least an anglophone poet in Canada, can seem sometimes near impossible. Sheer incomprehension and yawning indifference can drive one to despair, let alone those of us already perhaps too self-critical or reflective. At times, however, we may be fortunate enough to encounter those with heart enough to speak their appreciation for our work in our hearing. It was during one dark patch I called to mind those who had so praised me, remembering them in the following poem (which hopefully remains unfinished!).

Leave a comment

Leave a comment