Archive for the ‘The Brouillon’ Category

Two poems out at The /tƐmz/ Review

The /tƐmz/ Review has kindly published two “minimalist” poems from my manuscript-in-circulation Blank Song, “Epitaph” and “Ars Poetica: the eloquence of the vulgar tongue: ‘The top global stories that matter’.”

You can read them, and many other poems and stories, here.

Poetry Month—2025

April is National Poetry Month, and it will (“cruelly”) be observed in an overwhelming number of ways. These observations will invariably (and for obvious reasons) take poetry as an art form and in terms of its place in the world as a given, unproblematic. But is the matter really so simple?

In the lecture “What Are Poets For?” (first delivered in 1946, later revised, collected, and published in Holzwege in 1950), Martin Heidegger says of those poets in dürftiger Zeit (literally, “a desperately impoverished time”) that “It is a necessary part of the poet’s nature that, before they can be truly a poet in such an age, the time’s destitution must have made the whole being and vocation of the poet a poetic question…” Heidegger’s compatriot, Theodor Adorno (for all their differences), expresses a similar thought in his unfinished Aesthetic Theory (1970): “It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident anymore, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.” Have matters changed so much since? Is poetry—as an art, in the vocation of the poet—today now so self-evident in its “inner life,” its “relation to the world,” its “right to exist”?

One might be forgiven, of course, for suspecting these philosophers of not taking poetry or Dichtung (roughly, literature) seriously, dismissing it, as have many philosophers since Plato, who accused poets of being liars. Of course, in the case of Heidegger and Adorno, such suspicions would be unfounded. During the Second War, Heidegger famously turned to Hölderlin as a primary source of his thinking, and Adorno, throughout his career, wrote not only (and at length) on music, but on literature, as well, as the volumes of his Notes on Literature attest. One might even venture that Adorno pointed to Samuel Beckett (especially his novel The Unnameable) as a poet (Dichter) for our dürftiger Zeit.

What makes the time, at least of the two philosophers here, so “destitute”? What has pulled the rug from under, if not removed the very ground beneath, the “self-evidence” of art? Heidegger delivered the first version of “What Are Poets For?” at the end of 1946. Germany and much of Europe lay in ruins, Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been reduced to radioactive ash, and the horrors of the Holocaust were coming to international light. In March of the same year, Winston Churchill had already spoken of “the Iron Curtain.” By the time of Adorno’s death in August, 1969, matters had arguably worsened. Not only had the Cold War intensified, raising the risk of Mutually Assured Destruction, but the ecological crisis was becoming a cause for concern, all aggravated by the developed world’s being increasingly, suffocatingly administered under the rule of technocratic, instrumental reason. From the point of view of Geist (“spirit”), even before 1946, radio, recorded music, and cinema, indeed commercial media had begun to displace so-called “High Art,” a development impacting T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland (1922) and bewailed at length and in detail by critic F. R. Leavis. By the time of Adorno’s death, television had been added to this mix, cultural production “proximally and for the most part” now determined by the “Culture Industry.” The grounds for Adorno’s declaration, above, are arguably more involved (such was the sophistication of his thinking), but the desperation of their time, the beginning of our own present, desperate time, is not difficult to discern.

And today? The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is at its highest point in 800,000 years, pushing the climate out of the temperate, post-Ice Age Holocene, the matrix for human civilization as we’ve known it, into one Homo Sapiens have never inhabited. Micro- and nanoplastics contaminate every cubic centimeter of soil on earth and every tissue in the human body, including the brain. That brain’s capacity for attention and focus has been disrupted by digital media, which has whipped the public sphere to a froth. Just before the Second War, Yeats famously wrote that “the centre does not hold.” Not long before, the human capacity to know nature arguably hit a limit in the paradoxes of the quantum realm, and human reason, at least in its logical aspect, foundered at its limit, drawn by Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. Ironically, what could be known of, or at least drawn from, that same quantum realm, enabled the detonation of the A-bomb, simultaneously enabling humankind to destroy itself and creating a never-before-seen mineral, Trinitite. Not only has the ground fallen from beneath us (in the limits discovered to physics and logic), but the future is at best unknown and at worst foreclosed. For all its often plodding portentiousness, Heidegger’s essay understands the dürftiger Zeit in Hölderlin’s “Bread and Wine” as a night nearing midnight, a reaching into the abyss; from this present moment, a prophetic insight. What in this now is self-evident in its “inner life,” “its relation to the world,” its “right to exist”?

Another poet, Rimbaud, writes that “we must be absolutely modern,” a statement as descriptive as prescriptive. On the one hand, we can’t help but be “absolutely modern,” of our time, a moment so intimate knowledge of it eludes us, that which is closest being farthest away, as Charles Olson paraphrases Heraclitus. Despite our inescapably absolute modernity, we are always too late, especially in our hypermediated present, when everything happens too quickly (culturing that modern malady of the Fear-of-Missing-Out). That “we must be absolutely modern,” then, becomes a condition for our meeting, living up to (if not through) our present, desperate predicament. In absolutely modern terms, Hölderlin’s question, Wo zu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit? (“What are poets for in a destitute time?” in one translation), becomes, in part, What are poets, what is poetry, for on a planet humankind has never inhabited (and may not inhabit for long)?

If we are to observe (as we have a little here), let alone celebrate, National Poetry Month, we might do so a little more “cruelly,” facing, squarely and clear-eyed as possible, the predicament of the moment and its consequences for the art of poetry and its place in it. Surely, however, such a challenge doesn’t call for (critical, let alone “philosophical”) reflection alone: responding to the desperation of a time that calls everything—and poetry with it—into question might equally call forth poetry itself, just no longer a poetry harmonious and fit with an era irretrievably fallen into the abyss of the past, but one aspiring to be equal to—as new, as modern—as our unprecedented moment and, hopefully, future. Only a poetry that surrenders its complacent self-understanding and confidence in its place in the world—a world long gone—can begin to remake itself as poetry—poiesis, making—uncanny (unheimlich, no longer at home), unrecognizable—yet, thereby, something recognizably made new—alive to a moment that might be imagined to need it most.

Hell’s Printing House: In Canus Major (2009)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

As usual, the two short poems and two sequences this chapbook collects were collated for a poetry reading the summer of the year in the subtitle.

They were collated according to their shared influence, under the sign of the Dog, which is acknowledged in the title’s resonances. One the one hand (paw?), the title refers to the constellation; on another, it suggests that the poems are composed in the key of the Dog. As well, the “title track” is titled “Dog Days.” The “dog” here is Diogenes the Cynic (pictured on the cover), whose given name rimes with ‘dog’ (“dog-genes”) and whose title is derived from the Greek kynikos, literally “dog-like,” from kyōn (genitive kynos), ‘dog’. The original Cynics were termed so because of their shameless behaviour, including urinating, defecating, masturbating, and copulating in public. (Interested parties are urged to consult The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in Antiquity and Its Legacy, eds. Branham and Goulet-Cazé, the volume which informs the take on Cynicism at work, here).

The poems/sequences collected are

- “Welcome Home”

- “Intimations of Mortality”

- “Moundt Royall one circuit”

- “It’s not that you’re young and pretty…”

- “I want to know…”

- “Re: De Rerum Natura IV: 1052-1287”

These last three poems are the sequence remarked above, “Dog Days,” now subtitled “after Corvus Sanctus the Cynic (fl. 64 BCE),” a subtitle intended to underline the poems’ stemming from the traditions of both Cynicism and classical Latin poetry, especially that of Catullus and Juvenal, both known for their forthright, unapologetic bawdiness.

I read this sequence, here.

Next month: Blank Song and other poems (2017?):

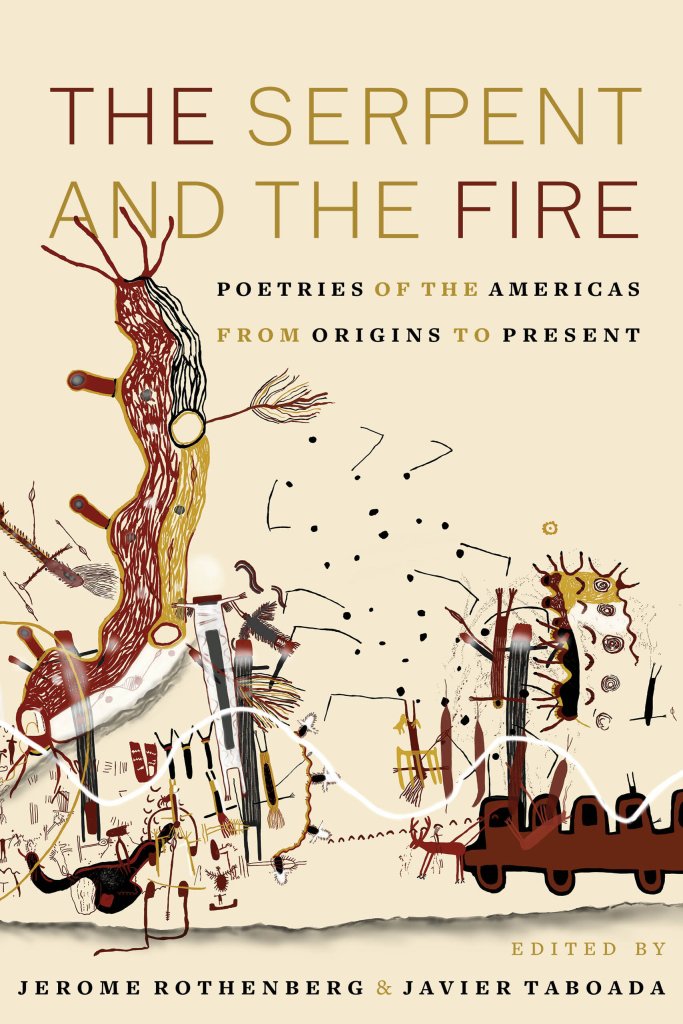

The Serpent and the Fire and Louis Riel

This month marks the publication of the final assemblage of Jerome Rothenberg (with co-editor Javier Taboada), The Fire and the Serpent.

As the publisher’s website tells us:

Jerome Rothenberg’s final anthology—an experiment in omnipoetics with Javier Taboada—reaches into the deepest origins of the Americas, north and south, to redefine America and its poetries.

The Serpent and the Fire breaks out of deeply entrenched models that limit “American” literature to work written in English within the present boundaries of the United States. Editors Jerome Rothenberg and Javier Taboada gather vital pieces from all parts of the Western Hemisphere and the breadth of European and Indigenous languages within: a unique range of cultures and languages going back several millennia, an experiment in what the editors call an American “omnipoetics.”

The Serpent and the Fire is divided into four chronological sections—from early pre-Columbian times to the immediately contemporary—and five thematic sections that move freely across languages and shifting geographical boundaries to underscore the complexities, conflicts, contradictions, and continuities of the poetry of the Americas. The book also boasts contextualizing commentaries to connect the poets and poems in dialogue across time and space.

Included in the volume’s vast spatiotemporal range are poems by bp Nichol and Nicole Brossard, along with a contribution by myself and Antoine Malette, translations of some sections of Louis Riel’s Massinahican. To whet your appetite, I invite you to sample that translation and some remarks about it, here.

And, as an added bonus, I invite you to save 30% when you purchase a copy of this book from the University of California Press website: just enter code EMAIL30 at check out. (Hopefully the cost of shipping and handling won’t negate the savings…).

A Metonymic Ideogram Concerning Poetic Attention

I’ve resisted writing the following, but a small flurry of persistent synchronicities insists otherwise.

It began with a Facebook discussion thread, prompted by a Canadian anglophone poet of my acquaintance. “Saw the list of this year’s Griffin judges. If we have a Canadian nominee other than Michael Ondaatje’s poetry collection A Year of Last Things I will be surprised.”

Around the same time, I happened on a remaindered copy of Hans Blumenbergs’s Work on Myth, and two poetry collections by Daniel Borzutzky (The Ecstasy of Capitulation and The Performance of Becoming Human) arrived, along with Jerome McGann’s The Point Is to Change It: Poetry and Criticism in the Continuing Present.

In the opening pages of McGann’s book “The Argument,” McGann observes “[Walter Benjamin and Gertrude Stein] both approach the history of poetry as an emergency of the present rather than as a legacy of past. The emergency appears as a poetic deficit in contemporary culture, where values of politics and morality are judged prima facie more important than aesthetic values.” Regardless of one’s knowledge or opinion of Benjamin or Stein, McGann’s invocation of “emergency” is provocative, to thought and otherwise.

Then, today, Norman Finkelstein’s Restless Messengers posted a three-part piece on Michael Boughn, a brief introduction by Miriam Nichols along with a review of his latest poetry book and a book of essays (by Finkelstein, required reading). Reviewing that poetry collection, The Book of Uncertain A Hyperbiographical User’s Manual (Book One), the reviewer, John Tritica, remarks “Michael Boughn does not write what Jack Spicer called one night stand poems, those shiny, reader-friendly, award-winning, readily consumable poems so prized by mainstream anthologies and awards institutions.”

Readers with an ideogrammic/metonymic sense will surmise what I’m on about here. I’ll let this juxtaposition speak for itself…

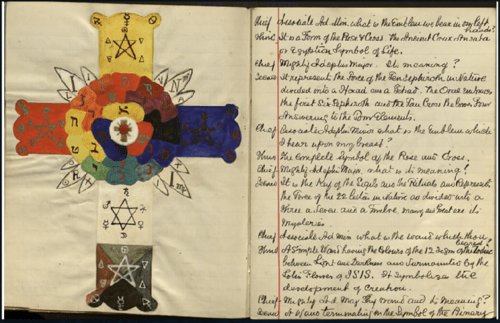

Crosspost: Three “occult” poems

A post concerning the place of “the occult” in my poetry, with readings from three poems from Grand Gnostic Central, Ladonian Magnitudes, and March End Prill.

Read, and hear!, here.

chouette Number One, Spring 2024 is live!

chouette, a new, online literary periodical based in Montreal has published its first number. It includes, among much else, two poems of mine, “Simulacra” and “A lot of poets…” along with a poem by a student of mine, Carla Frey. You can read chouette, Number One, here.

As well, I’ve recorded “A lot of poets…” for your listening pleasure, hearable, here.

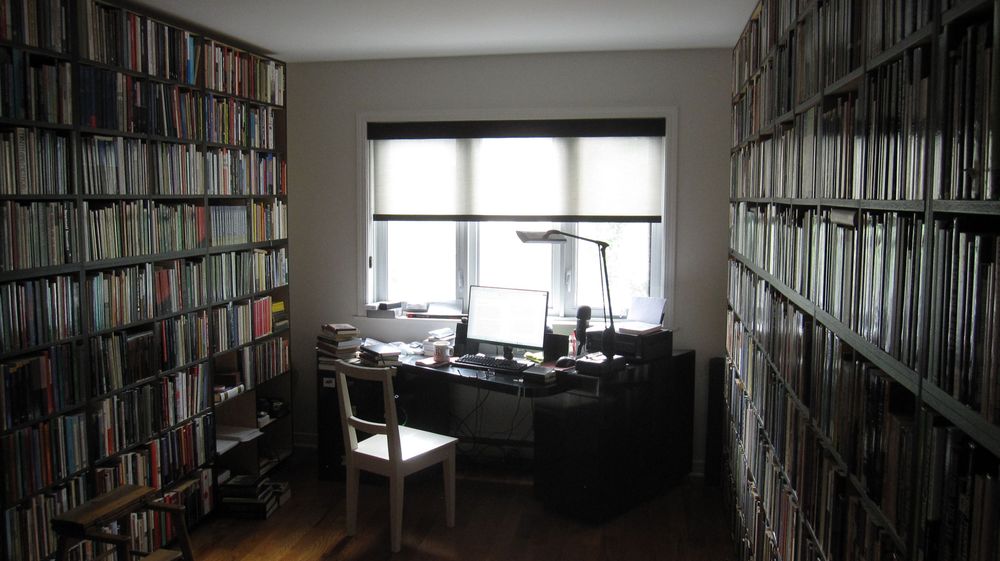

Shelf Portrait

The good folks at The Richler Library Project at Concordia University have shared my “Shelf Portrait,” a brief piece on my home library. The essay ranges over the contents, organization, and use of my books and includes a few, choice pictures.

One addendum, mind you: the photo of a sample of my ufological library, is hardly of “Works on cosmicism, astrology[?!], and space exploration, among other celestial subjects“!—It’s all about UFOs and related matters from a wide variety of angles!

You can read my Shelf Portrait, here. Why not browse all the others, here?

Much gratitude to Jason Camlot, scholar, poet, and musician, for soliciting the piece.

Resist, much?

It was and remains an aesthetic, critical, compositional commonplace in some circles that the poem that resists ready understanding resists the capitalist order that would reduce all things to readily consumable commodities.

There are, of course, at least caveats to this position. No text, however transparent, is ever absolutely so, or it would be invisible. That is, all language is possessed of an aesthetic aspect (phonic, graphic, or tactile) as a condition of its possibly serving as a communicative or aesthetic medium at all; its materiality is inescapable. Moreover, no poem can possibly give over its reserves of meaning. “The words on the page” (to invoke a hoary critical paradigm), under sufficient scrutiny, betray an interpretive wealth far in excess of their immediate, prosaic, “literal” meaning. Even more, as a text, the poem is woven from and thereby back into other discourses; it is implicated in a very complex way in its culture. Furthermore, being a temporal phenomenon, that is, existing through time, this con-text will vary; being “fatherless,” the poem will be variously resituated, recontextualized, by ever new readers and thereby made to resonate in new, unforeseeable and uncontrollable ways. And one would be remiss to not remark most critically that it is not the poem that is, strictly, commodified, but what contains it, the book, periodical, or website; the poem is not consumed, per se, but the “thing” that packages it, which is bought and sold.

To these reflections, Abigail Williams’ Reading It Wrong: An Alternative History of Early Eighteenth-Century Literature seems to add a new angle. As the publisher’s description relates,

Focussing on the first half of the eighteenth century, the golden age of satire, Reading It Wrong tells how a combination of changing readerships and fantastically tricky literature created the perfect grounds for puzzlement and partial comprehension. Through the lens of a history of imperfect reading, we see that many of the period’s major works—by writers including Daniel Defoe, Eliza Haywood, Mary Wortley Montagu, Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift—both generated and depended upon widespread misreading. Being foxed by a satire, coded fiction or allegory was, like Wordle or the cryptic crossword, a form of entertainment…

Williams’ argument is compelling in at least two ways. First, her sample texts’ being resistant to understanding is precisely their appeal, their “selling point.” Second, the horizon of this elusive, allusive aesthetic is the early morning of capitalism in England, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, a famous index of the ideology of the moment. However, 2023 is not 1723, however much both are determined by a shared social formation, nor is the superstructure of these two moments the same. (Habermas’ forthcoming A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics is all the more looked forward to in this regard). Nevertheless, Williams’ study complicates the still vital, urgent demand to think about the place and function of poetic language in our present, critical moment….

AN OMNIPOETICS MANIFESTO, from PRE-FACE TO A HEMISPHERIC GATHERING OF THE POETRY & POETICS OF THE AMERICAS “FROM ORIGINS TO PRESENT”

I share here an excerpt from the Pre-face to Rothenberg’s and Taboada’s forthcoming assemblage of poetry and poetics from the Americas, from origins to the present. Not only is the omnipoetics manifesto therein of overriding interest in its own right, but Rothenberg’s and Taboada’s anthology also includes a translation from Louis Riel’s Massinahican by Antoine Malette and myself, some of which can be read, here.

The post, first published 4 October 2023, at Rothenberg’s Poems and Poetics blogspot can be read, here.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment