New Poem up at Canadian Literature

Canadian Literature (#256) has very kindly published my poem “By Mullet River” (with commentary!) in its latest issue. You can read that poem, and all the other poems, reviews, and articles, here.

Hell’s Printing House: A Crow’n’ o’ Sough Noughts (2004)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

It was July 1991 I sat down one morning in a more relaxed compositional mood and wrote the following poem.

It was only after I had written these lines that I remarked there were fourteen. This unconscious compositional chance was fortuitious, for, as I’ve previously remarked, the sonnet sequence was all the rage in Canadian anglophone poetry circles at the time. Recently, I’d read, too, Charles Bernstein on Ted Berrigan’s sonnets along with the sonnets themselves, and I remembered having read much else about the history of the form, all of which was brought into focus by William Carlos Williams’: “all sonnets say the same thing.” What this vortex suggested to me was a nonintentional, chance-governed satirical practice: I wouldn’t set out to write “sonnets” or poems of fourteen lines (which many of the “sonnets” written at that time amounted to) but, rather, when I by chance wrote a poem of fourteen lines, I’d dub it a “sonot,” “soughknot,” or “soughnought” (‘sough’: the high or low long sound that something such as the wind or sea makes as it moves”)…

Over time, these sonots accrued. Some appear in the chapbooks to date, two are collected in Grand Gnostic Central (DC Books, 1998), and two dozen (as soughknots) in Ladonian Magnitudes (DC Books, 2006). I don’t know how many more I have written since. In the publishing lull following Ladonian Magnitudes, that fashion for sonnet sequences unabated, I was moved to gather twenty-five soughnoughts in a chapbook under the punny title A Crow’n’ o’ Sough Noughts. The collection is prefaced by a short epigraph: “A place to stand / A corner to loiter // To listen to the small / Sounds around.” Those not unacquainted with the etymologies of ‘sonnet’ will understand. On a visit to Ottawa at the time, I gifted a copy of the chapbook to one of Canada’s most prolific poet/reviewers, on whom, sadly, the joke—of both the epigraph and the collection as a whole—was lost, a too common reception…

Below, the table of contents. An asterisk marks those soughnoughts collected in Grand Gnostic Central, two, those in Ladonian Magnitudes. Those already shared here at Poeta Doctus are, of course, linked.

- “A piss…”**

- “Church bells ring loud…”**

- “Clear nights I look up…”**

- “Come out of the cave…”**

- “Comn home th’other afternoon…”**

- “As I delighted with the enjoyments of torment…”

- “Every afternoon I lie on the couch…”

- “Grave as Spring is green…”**

- “I HATE POETRY”**

- “I know the ‘aurora borealis’…”*

- “20:02 20.02.2002” (“Inside / dark out…’)**

- “I watched…”**

- “Master of many styles…”**

- “My brother the dr called today…”**

- “Gloze”*

- “20:02 20.02.2002″ (Not a right word…”)**

- “Lizard Song”**

- “Colleague Didactics”**

- “if you wanted to put yrself thru phd torture – mcgill or suny?”**

- “The great works…”*

- “The Kings and Queen of Qawwali chants”**

- “An Apology to François Hubert”**

- “When every hand is styled”**

- “With…”

- “‘you can pick up yr share…'”**

There are a number of these soughnoughts I’m moved to share: “Master of many styles…,” a favourite of Rui Chafes, an eminent sculptor from Portugal I met at the Villa Waldberta in Summer 1997, or “if you wanted to put yrself thru phd torture – mcgill or suny?” my friend the Munich-based novelist and publisher Georg Oswald lauded for its modernity, but one, published in Grand Gnostic Central, has proven to be “a fan favourite,” “I know the aurora borealis…,” which you can read, and hear, below:

Next month: Tanchaz!

Hell’s Printing House: For a Few Golden Ears (2004)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

I had published my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central and other poems in 1998, and I was feeling the growing lag between that publication and what would be next, Ladonian Magnitudes (2006). At the same time, it was becoming increasingly impressed upon me not only how relatively small was the audience for poetry, but how much smaller the circle of my own readers seemed. Taking heart from Allen Ginsberg’s having composed Howl for his “own soul’s ear and a few other golden ears” (a sentiment echoed by Cseslaw Milosz, “I was convinced that we write for perhaps about twenty or thirty individuals, for our fellow poets”), I gathered fifteen poems, published and unpublished, explicitly dedicated to or otherwise written for those lovers, collaborators, friends, and acquaintances in that small circle.

The collection opens with what I have variously called ‘sonots’, ‘soughknots’,or ‘soughnoughts’ in parody of the many books of sonnets being published by anglophone Canadian poets at the time. For a Few Golden Ears gathers, as well, “condensations” (poems composed by making couplets of the first and last lines of another poem’s stanzas), collage acrostics, “quotation” poems stitching together lines overheard, “cubist” poems playing out all the definitions of the words in the poem’s title, letter poems and poems from letters, long-lined rhapsodic poems, curt images, and a manner of abuse poem. All but five of these were to be included in Ladonian Magnitudes (those orphan poems are indicated by ‘*’ below). Those golden ears were and are found on the heads of Rainer Christ, Laszlo Gefin, Ty Hochban, François Hubert, Daniel O’Leary, Georg Oswald, George Slobodzian, Zsolt Sörés, Andrea Strudensky, and my wife, Petra—and, of course, anybody else with “golden ears” to hear!

Contents

- An Apology to François Hubert*

- In the Rialto Before Prospero’s Books*

- See Garden

- Decay Pattern

- C B Hsien Hue on Woman*

- Of Poundysseus

- From a Letter

- Das München Mädchen

- Dream Notes (Bochum, 20 May 1997)

- Reasons Why

- Elenium

- A Visitor from Jerry-Land

- Poésies*

- Epistle to Zsolti: Sunday 25 January 2003

- “For years you’ve been…”*

- Pisces

Yeats observes that “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.” “A Visitor from Jerry-Land,” however much an argument with its interlocutor, is, I argue, very much poetry:

Though I’ve shared “Reasons Why” before, I post it here again with a new recording, as it is probably the one poem of mine I wish had a wider hearing, especially in my home province of Saskatchewan. The poem is a kind of apologia. In the course of a conversation with my old teacher poet friend Laszlo Gefin, he pointed an accusative finger at me and exclaimed with a mixture of surprise and disapprobation that I was “some kinda universal welfare Tommy Douglasite!” The ensuing poem seeks—as much for myself as my accuser—to explain why.

Next month: A Crow’n’ ‘o Sough Noughts (2004).

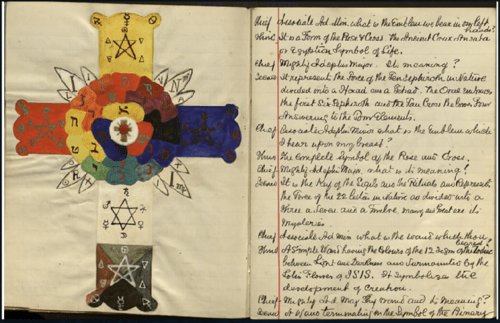

Crosspost: Three “occult” poems

A post concerning the place of “the occult” in my poetry, with readings from three poems from Grand Gnostic Central, Ladonian Magnitudes, and March End Prill.

Read, and hear!, here.

chouette Number One, Spring 2024 is live!

chouette, a new, online literary periodical based in Montreal has published its first number. It includes, among much else, two poems of mine, “Simulacra” and “A lot of poets…” along with a poem by a student of mine, Carla Frey. You can read chouette, Number One, here.

As well, I’ve recorded “A lot of poets…” for your listening pleasure, hearable, here.

An Old Man’s Eagle Mind: on Peter Dale Scott’s Dreamcraft

The publication of Peter Dale Scott‘s latest volume of poetry is bookended by last year’s appearance of his study of Czeslaw Milosz, Ecstatic Pessimist, and this year’s release of Reading the Dream: A Post-Secular History of Enmindment, quite the trifecta for a man who turned ninety-five in January of this year (2024).

The poems collected in Dreamcraft, on might say, have vista. This latest volume’s being published in the poet’s ninety-sixth year, it comes as no surprise to find poems on old age. “Eros at Ninety” is both humbly, humorously self-deprecating and wise. “A Ninety-Year-Old Rereads the Vita Nuova” and “After Sixty-Four Years” ruminate over the changing experience of art, here, that of Dante and Grieg, within a lifetime’s perspective. The longer one lives, the more acquaintances one loses to death: elegies for lost friends—Robert Silvers and Scott’s lifelong friend Daniel Ellsberg, among them—take up nearly a third of the book. Four poems are addressed to Scott’s friend, Leonard Cohen, the book’s title track, “Dreamcraft,” the explicit elegy “For Leonard Cohen (1934-2016),” “Commissar and Yogi,” and a poetic back-and-forth the two shared just before Cohen’s death, “Leonard and Peter” (included, as well, in the last collection of Cohen’s work, The Flame). The volume’s perspective, from within “the long curve of life” (words from the book’s first poem, “Presence”) is evident in the poems that embed the poet in larger processes, whether “the bicameral brain that makes // obsfucation of mere fact / so much more beautiful” (“The Condition of Water”), our genetic character (“Dreaming My DNA”), the Earth itself (“Deep Movement”), “cosmic space / …knowable / by those specks of light // at great distance from each other,” or History’s ethogeny, which Scott glosses as “cultural evolution” (“Moreness”). Loss and the long view bring the poet’s closest relations into focus in more intimate poems, those for his daughter, Cassie (“To My Daughter in Winnipeg” and “Missing Cassie”) and wife, Ronna Kabatznick (“Enlightenment” and “Red Rose”).

Last year’s publication of Ecstatic Pessimist: Czeslaw Milosz, Poet of Catastrophe and Hope reveals Milosz as a kind of éminence grise in Dreamcraft (and, indeed, throughout Scott’s poetry). Though their friendship at the University of California, Berkely, was short-lived (roughly from 1961-1967), Milosz’s notions of the function of poetry and the poet, as one whose “poetic act both anticipates [an emancipated] future and speeds its coming,” are determinative: anyone at all familiar with Scott’s poetry and prose will hear the echo of Milsoz’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “In a room where people unanimously maintain a conspiracy of silence, one word of truth sounds like a pistol shot.” Scott’s lifelong relationship to Milosz’s poetry and thought, if not with the man, finds expression in the five-part sequence “To Czeslaw Milosz,” wherein Scott reflects on that relationship, one Polish word or one poem or idea at a time. This sequence is balanced, as it were, by “The Forest of Wishing,” originally published in 1965, which addresses (among other things) Milosz’s reaction to the American Counterculture of the 1960s in an earlier style of Scott’s, remarkable for a more elusive density of suggestion than is found in his poetry from Coming to Jakarta (1988) to the present volume.

Scott’s mature style might be said to take its cue from Milosz’s admonition (also from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech) that the poet need “liberate [themselves] from borrowed styles in search for reality.” The result, in Scott’s case, is sure to irritate those readers who need their poetry to “tell it slant” (whether that spring from a post-Eliotean prejudice for “metaphor” or a post-Language demand that the linguistic medium be estranged, if the aesthetic inclination is even so self-aware). A case in point might be the poem “Pig”:

Aside from the poem’s being a recognizably generic “lyric” (a first-person anecdote climaxing in an epiphany), I can well imagine readers with a taste for the mimetic virtues of, say, Seamus Heaney, Eric Ormsby, or (more recently) Kayla Czaga, or the verbal deftness of Michael Ondaatje at his best, dissatisfied with the description of the pig’s butchering (in the second, third, and fourth tercets), desiring in place of, for example, the words ‘slaughtered’, ‘cutting’, and ‘squealing’ at least a more sensuously robust diction if not a vividly inventive image to present rather than refer to the action. Such readers would be even more scandalized by the poem “Mythogenesis” with its opening “The OED defines / both mythopoeia and mythogenesis / as the same: the creation of myths,” lines which set the tone for the explicatory prosaicness of the poem that follows (a prosaicness, however, that slyly reproduces, line for line, the original email sent to the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary). I, too, have struggled for my own reasons with this tendency in Scott’s style over the years, and, were this notice a “review,” I’d be obliged to indulge in the workshop nit-pickery that would find fault with (“criticize”) a certain word choice here, a syntax that might be made more mimetic there, or even the collection’s title, but such an approach too often merely brings into view the reviewer’s prejudices or limitations (let alone the hatchet they might have to grind) than serving to illuminate the work under consideration (a problematic addressed, in fact, by the book’s penultimate poem “A Quinkling Manifesto”). Scott, himself, has responded to critics who find his poetry too prosaic, reminding them the same accusation was levelled at the prosody of Williams Carlos Williams a century ago. One could point to that other compositional sensibility (with which Williams was briefly associated) present in the “Objectivist” poets (notable for their engagement), among them, Lorine Niedecker, Carl Rakosi, or Charles Reznikoff. But more to the point, it is precisely this clinamen of Scott’s style, the way it swerves from any such obvious borrowings or influence, that is an index of that essential drive in his entire oeuvre, a “search for reality,” the telos of his work that is the principle measure of its success or failure, if a critical judgement is indeed called for.

As I’ve observed, the poems in this latest (if not last) volume take the perspective of “an old man’s eagle mind” (as Yeats called it), wherein “the long curve of life” becomes visible, the horizon for whatever else might come into view. This perspective is, perhaps, no more evident than in the book’s final, thought-provoking poem with its explicitly ethogenic theme, “Esprit de l’Escalier“:

The poem, in post-secular fashion, has as its epigraph a verse from the Book of Zechariah (4:6) (Scott the first to my knowledge to articulate a post-secular sensibility, in advance of Habermas’ developing the concept in its present form in 2008), a verse with tonal implications for what follows. We are admonished to “not just talk about politics // which let’s face it / we can do nothing about” (at least those of “us here / at this Chanukah table”) but “about culture // preparing people’s minds / for tomorrow’s revolution” (words which, again, echo Milosz’s “The poetic act both anticipates the future and speeds its coming”). Curiously, the poem speaks of a “black windshield” (likely the image that, in part, inspires the book’s cover art) “smeared… // with the grime of facts,” a brow-furrowing sentiment to flow from the pen of so assiduous a researcher, whose work, prose and poetry, has laboured to uncover that “conspiracy of silence” and scatter it with a resounding “word of truth.” (That is, perplexing as long as we remain insensitive to the potential tonal complexity of ‘facts’ and the even more important and profound distinction to be made between “facts” and truth…). This grime is to be cleaned “with hope,” a hope that waits for “the great poet // on whose shoulder / that eagle flying / above and ahead of us // in the darkness / will come down briefly to rest.” These lines are richly suggestive. On the one hand, they mark Scott, I think, as one of those increasingly rare poets who demand poetry play an orienting if not guiding role in culture and society. On the other, that “eagle flying / above and ahead of us” is at first elusive as allusive. Is it a mere—if complex—metonymy, invoking the eagle’s powers of sight? Does it allude to the eagle formed by the just souls in the heaven of Jupiter in Paradiso XIX? Is it a symbol of God, via the bird often associated with Zeus (‘Z-eus’, ‘d-eus’ (which, regrettably, only rime with ‘th-eo’…))? More tentatively, it brings to this mind, anyway, the idea of the kommende Gott, the “coming god” in Hölderlin’s “Bread and Wine” (however much that god is, in fact, Dionysius…), perhaps that god who is the only one “who can save us” in Heidegger’s late, portentous phrase. This interpretive question is resolved, however, by turning to Reading the Dream, where we discover Scott’s eagle alludes to the spirit of Rousseau in Hölderlin’s ode to the French thinker, that “flies as the eagles do / Ahead of thunder-storms, preceding / Gods, his own gods, to announce their coming” (“wie Adler den / Gewittern, weissagend seinen / Kommenden Göttern voraus“). The rich figurative resonance of these lines that demands such learned, interpretive labour marks them, too, as belonging to a past, if not passed, poetic, one rarely practiced today, if at all.

For many, I think, Scott’s vatic stance in this poem (however domesticated in its opening scene) and the faith in poetry it expresses will place him beyond a certain pale. The present, at least North American, mood is more skeptical. Those with some historical sense will too easily remember those poets who aspired to influence, cultural, social, and political, and went “wrong, / thinking of rightness.” Auden’s words, “poetry makes nothing happen,” still express a common sentiment, and, for those who do engage the question of the relation of poetry and politics seriously, it remains an open-ended, complexly recalcitrant problem. In his defense, Scott, in Ecstatic Pessimist, invokes Virgil, Dante, Blake, Shelley, and Eliot (6). More forcefully, Scott’s study of Milosz is a sustained argument for the potential social force of poetry, exemplified by his subject, notably “his contributions in the 1950s and 1960s to what became the intellectual culture of Solidarność” (5). What is striking is how this last poem in Dreamcraft departs from Scott’s characteristic poetry-of-truths that ring out like “a pistol shot.” It might be argued that its prophetic vision, of that mysterious justice-to-come and its poet, draws on poetry’s power to posit the counterfactual (how matters could or should be, to paraphrase Aristotle), to imagine a non-place (u-topos), a place that is not because it is only yet-to-be, and only potentially so. In contrast to the probing of uncomfortable truths (facts) characteristic of so much of Scott’s poetry, the fictionality of the poem’s vision (its being (only) imagined) invites, demands, a suspension of disbelief (the condition of imagining what is not as if it were), evoking our Negative Capability, that ability to live “in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” By its very unreality, then, the poem evokes that resolve that poetry—and social action—require….

That Scott’s oeuvre in this way, from his Seculum trilogy to Dreamcraft, demands the engaged reader to consider and wrestle with the art of poetry, poetry and politics, investigative fact and visionary fiction is evidence of its sophisticated achievement. Such reflection, it has long seemed to me, is the condition for any understanding of poetry, worthy of the name, an understanding that needs precede any critical appraisal. This resistance to a ready assimilation to existing literary-aesthetic canons—despite the surface, apparently-prosaic transparency of the poetry—testifies to Scott’s poetry’s being poetry, making, creating works possessed of a novel uncanniness that adds something new, not merely accomplished, to the world of letters, if not the world-at-large.

(If so moved, you can purchase a copy of Dreamcraft by clicking on the book’s cover, above.)

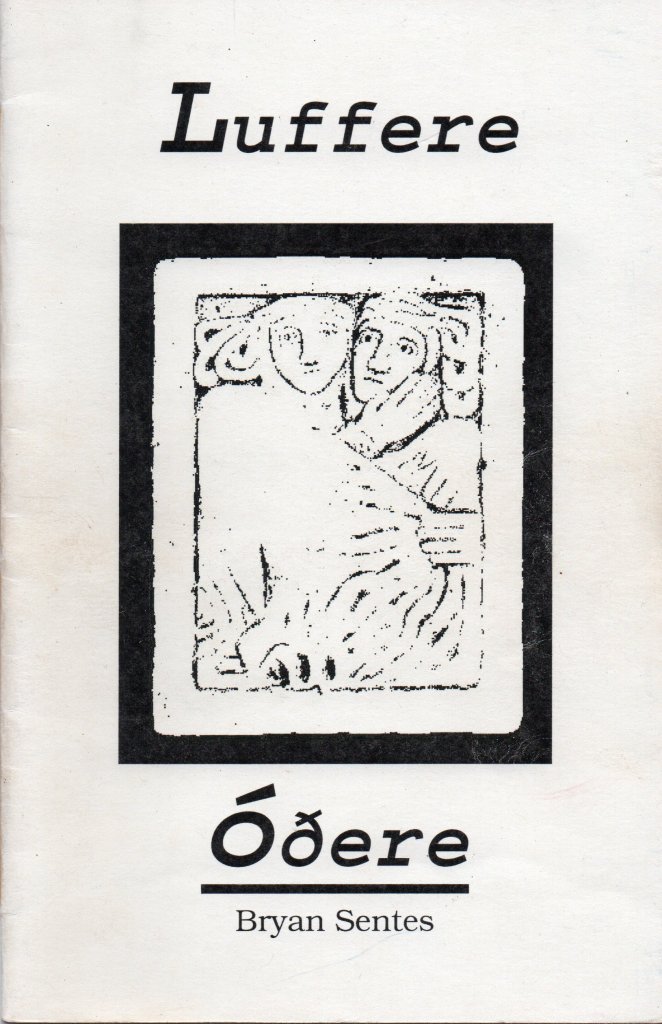

Hell’s Printing House: Luffere & Oþere: Amoretti from Marchend Prill (2003)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

The first five chapbooks I’d bound were made to collect and “publish” work otherwise unpublished in periodical or book form. Luffere & Oþere marked a departure, as it was the first chapbook that collated the poems I was to perform at a reading. At the time, Ilona Martonfi organized (among many other events) an annual Valentine’s Day reading, “Lovers and Others,” and kindly invited me to read. I don’t remember exactly what reasons I gave myself at the time, but it seemed somehow appropriate to have the poems I would read ready in print-form for interested parties, a good opportunity to issue a new chapbook, a practice I was to maintain for many years. Luffere & Oþere are the oldest forms of the words ‘lovers’ and ‘others’ in English.

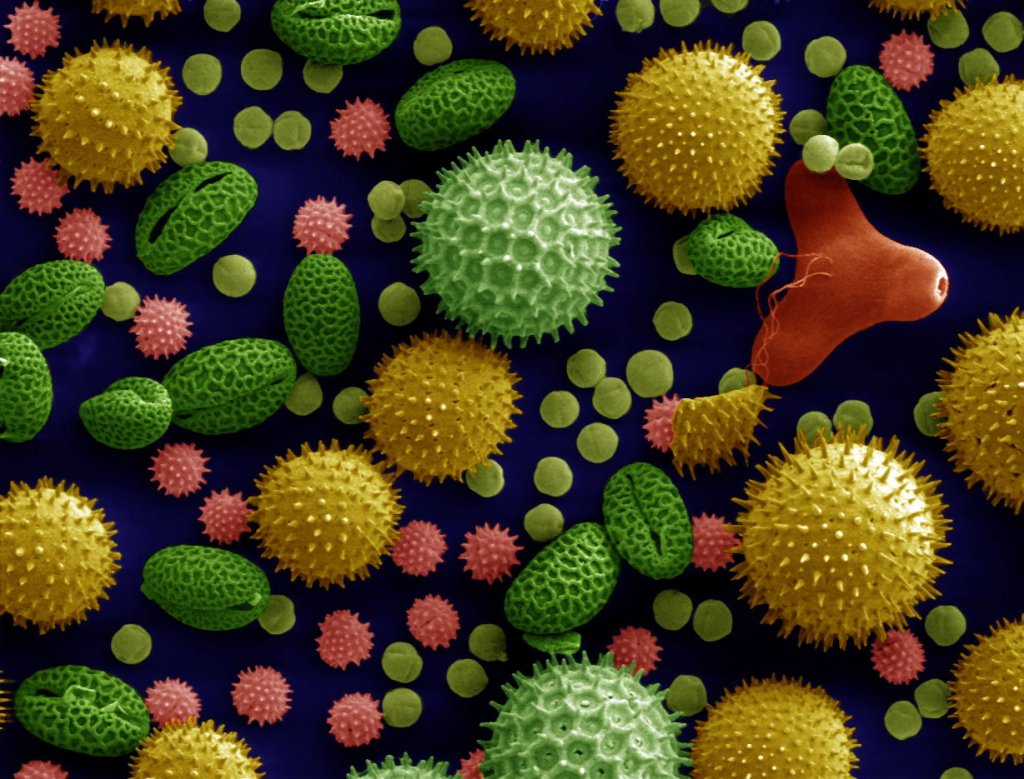

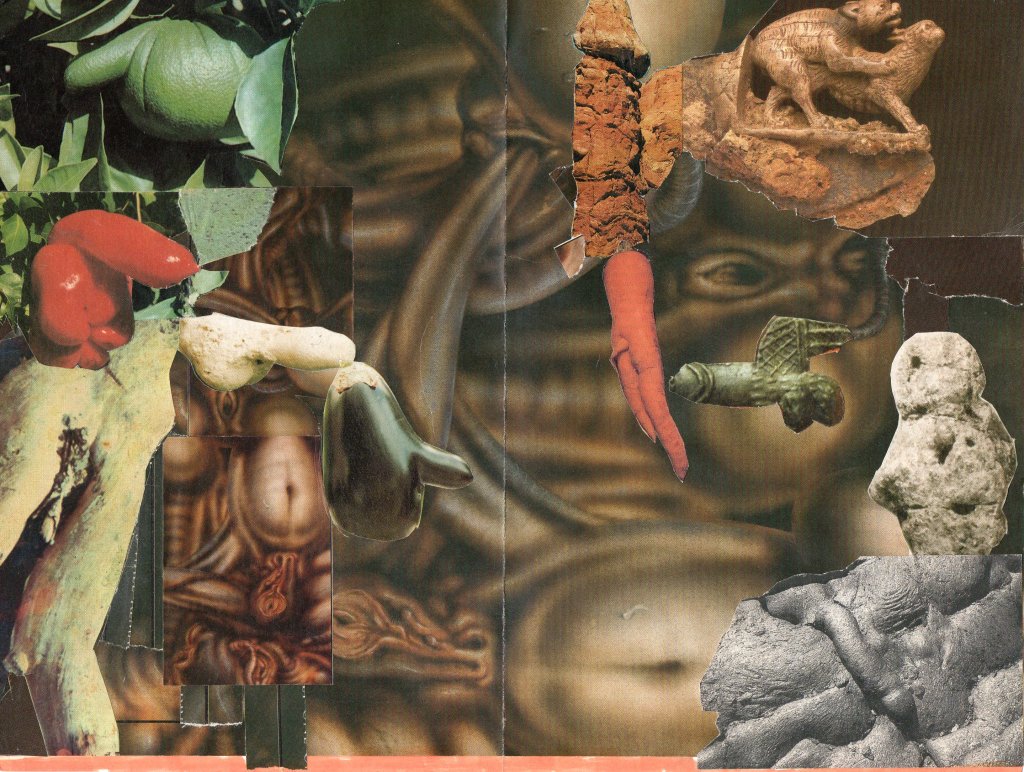

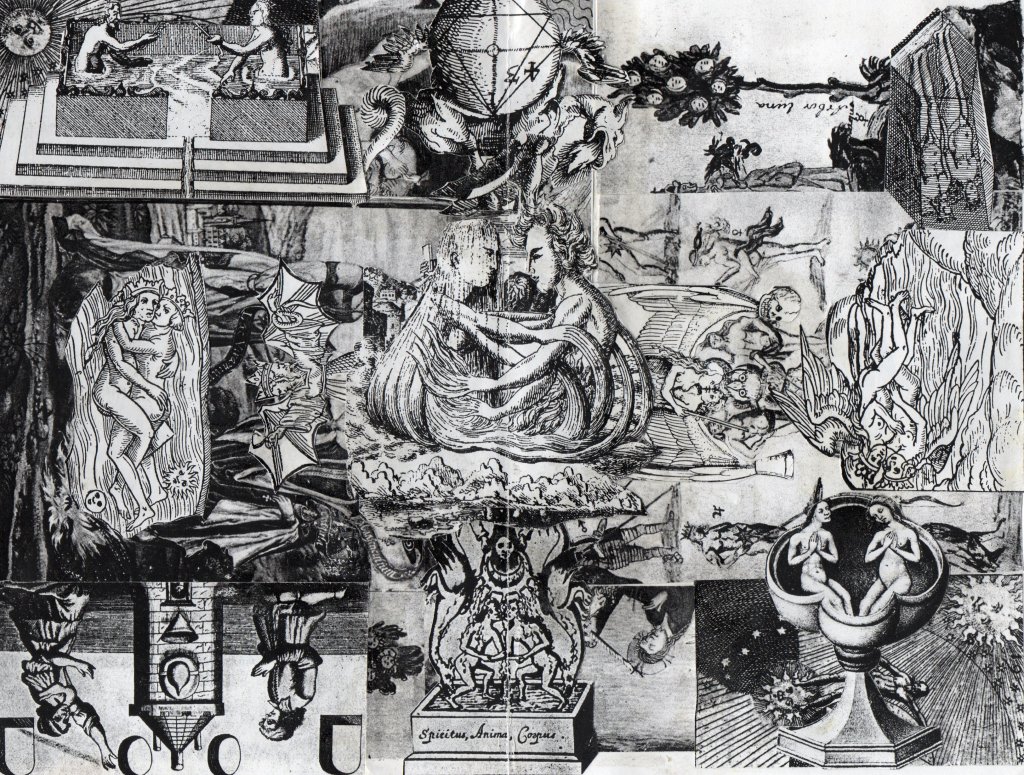

Not only was this chapbook the first made for a reading, but it is also the first with original artwork (in this case, two collages) for the flyleaf, outer and inner:

However much amor is one of the great poetic themes, it’s not one I have often dared (except for one poem, known only to my closest friends). However, at the time, I had written a poetic sequence, an extension of the concerns motivating X Ore Assays and Seventh Column, that was to be published years later in 2011 by Book*hug, March End Prill. This sequence, compositionally, adhered to a resolutely Surrealist poetic (“the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns”), informed as much by Breton as by ethnopoetics:

Songs are thoughts, sung out with the breath when people are moved by great forces & ordinary speech no longer suffices. Man is moved just like the ice floe sailing here and there in the current. His thoughts are driven by a flowing force when he feels joy, when he feels fear, when he feels sorry. Thoughts can wash over him like a flood, making his breath come gasps & his heart throb. Something like an abatement in the weather will keep him thawed up. And then it will happen that we, who always think we are small, will feel smaller still. And we will fear to use words. But it will happen that the words we need will come of themselves. When the words we want to use shoot up of themselves—we get a new song.—Orpingalik

At any rate, I combed through March End Prill and abstracted a sample of, if not all, the poems defensibly “erotic.” The titles are their first lines or the first words thereof:

Contents

- falling asleep

- she was coming for supper

- durée

- dear Wife

- we must really be out of touch

- Can’t wait for you

- mornings spooned

- When I get the chance

- my old friend dumped his

- Godammit! Love’s

- Bedrock

Here’s a new recording of these poems, for those who missed the reading!

Next month: For a Few Golden Ears (2004).

One for chouette

chouette, a new, online literary periodical based in Montreal, has kindly accepted two poems of mine for its inaugural issue.

One of the these poems, “A lot of poets…,” I record, here. It’s a versification of a colleague’s Facebook status from the opening days of the Pandemic. Thanks, again, to her, for allowing me to set her words to “the music we sing what we have to say to.”

On George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa

Culture must be—as the word itself might suggest—cultured, seeded and carefully tended. Such care takes many forms in Canada, from ever-diminishing (if however appreciated) government funding, to the selfless, meagrely-rewarded efforts of those who—in the case of our literary culture—publish small magazines and books of poetry, to more grassroots efforts.

In recent years, in Montreal, Devon Gallant and collaborators have cultured an urban poetic garden, organizing the Accent Reading Series, which combines an open-mic (as polylingual as the city) and a spotlight on one or two featured readers, and which has, accordingly, gathered a small, poetic community. One of the fruits of this endeavour is Cactus Press, which, to date, has issued over thirty chapbooks and the first trade edition of the unnervingly-talented Willow Loveday Little, (Vice) Viscera (2022).

One of the newest of these chapbooks is George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa, his second with Cactus Press. Apokryfa gathers eighteen poems, old and new, organizing them in three sections, “In the Garden,” “Et Homo Factum Est,” and “Tale.” The first reflects on childhood and youth, the second works up and on, more-or-less, Catholic mythology, while the last reworks fairy tales. However much at first glance these sections might suggest a progression from autobiographical truth to overt fiction, a more canny, poetic sensibility is at play that subverts such too-easy, hard-and-fast distinctions.

But this sophisticated sensibility is only one aspect of these eighteen poems, which, perhaps more importantly, reveal a poet at the top of his game. While, from the “Tale” section, “Other Dwarves” and “Deliverance” (a riff on “Rapunzel”), might seem relatively light, they are not without their wit (in the case of the former) or rich suggestiveness (in the case of the latter). Most of the poems are, however, so to say, more thematically substantive. “Radisson Slough,” recounting how the boy speaker “Out hunting with [his] father / and brothers, …was the dog,” concerns as much a moment in one’s lifelong loss-of-innocence as much as, perhaps, weightier epistemological matters when “in search of the warm reward / of a grain plump duck,” the boy finds “instead the corpse // of an abandoned crane / half-submerged and corrupt, / its great wings still engaged / in a sort of flight until” he touches it, and it sinks. “The Annunciation” in the chapbook’s second section, “Et Homo Factum Est” grimly recasts the Archangel Gabriel as the agent of some unnamed totalitarian regime with an uncannily ironic gift of prophecy who foretells the life of the expected son, a malcontent (and who wouldn’t be under such a system?) who leads “an entirely unremarkable childhood,” in the end only to “be taken / into the appropriate custody” to finally succumb “to his diseases.” And, in the book’s final section, that persistent question if not problem of “the Subject” (however much presently eclipsed by that of Identity) is taken up in a sly play on Delmore Schwartz’s “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” in “4th Bear” and the provocatively reflexive “Tale” (which begins: “in a dark forest I found you / not knowing you were / the dark forest and the trail / I was following was the trail / I was making those were / my own breadcrumbs…”).

Those with poetic ears attuned to melopoeia will already have remarked the deft, phonemic harmonies of “the warm reward / of a grain plump duck.” Slobodzian’s undeniable prosodic gift (which I have previously remarked), though present, is at once more under- and overplayed, as it were. Though passages of the quality of that from “Radisson Slough” are not infrequent, the language tends to be plainer, shaped more by rhythm than harmony; at the same time, there is, at times, a marked deployment of rhyme (especially in “Rapunzel”). But Slobodzian’s talent and artistry all come together perhaps nowhere most markedly as in “Pysanka (The Written Egg),” from the book’s first section. Here, a boy, barely out of infancy, sits with his grandmother as she draws a stylus “across the surface / of an Easter egg,” while the boy watches. The poem is a small tour de force in the ease with which it delineates a primal moment of culture (the grandmother’s “fingers [know] these things” and take the boy’s hand) and, reflexively, poiesis itself in the image of “the risen sun / a flaming rose / above an endless line.” These three lines should suggest just how extended an exegesis and appreciation the poem calls for.

Gallant and Cactus Press have surely done us a service in collating and sharing this handful of poems. One can only hope there is some acquisitions editor at a trade press with the savvy to offer to gather them into that full-length volume we’ve been waiting for for too long.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment