“Hell’s Printing House”: Seventh Column (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Saturday 22 September 2001 The Globe and Mail published an essay article by John Barber “Wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains” (F4). Despite its critical stance toward the then-impending invasion of Afghanistan by coalition forces, the terms of its discourse were so pedestrian my frustrated and bored eye wandered across its six columns. The article read thus, against the grain, appeared oracularly clear, and the experience of that reading what I wanted to communicate in the resulting poem. The sense this reading made to me leaves its trace in minor editorialisations (where the text has been stepped on). This vision into the essence of our imagination of Afghanistan is as forbidding as the country itself: a land of glacierous and desert mountains and sandstorms and tire-melting heat that swallows whole armies. “Cut the word lines and the future leaks through.” Here, English speaks this vision: in dead or obscure words, new compounds and coinages. Syntactically, at root (or so Norman O. Brown told John Cage) the arrangement of Alexander’s soldiers in a phalanx (the Great, too, stopped in Afghanistan), the language has been demilitarized.

Soon after I had composed the poem and printed and bound it in chapbook form, The Capilano Review called for submissions for a special issue “grief / war / poetics” that responded to the then-recent 9/11 attacks. It kindly accepted “Seventh Column,” just not the whole thing, so I had to decide how to excerpt a poem that, despite its disruptive, disrupted syntax, was still, arguably, a “whole.” I opted to have TCR print the first eight and last six stanzas to create a manner of sonnet. That excerpt can be read here, a reading of which I share, below.

“Seventh Column” is, to my mind, a high water mark of my poetic practice, the most carefully, rigorously composed of any of my poems. The lineation and punctuation intentionally follow no consistent rule (some lines are end-stopped, others enjambed, some sentences begin with capitals and end with periods, others not…); words are sometimes broken into their syllables, resulting in new coinages or echoes of an older English (whose meanings are footnoted). The language is thus “made new” and impossible to dominate or domesticate by a hermeneutic will-to-meaning lacking sufficient Negative Capability. Indeed, the poem eluded even my own compositional rigor, somehow making itself circular, ending with the suffix ne- and beginning with the root -glected…

Next month: Luffere & Oþere

New Poem up at Montreal’s own Columba

As my friend Erin Mouré writes, “Aye Columba!” Montreal’s own online poetry periodical has been kind enough to publish a poem of mine along with those of four others, one of whom, Domenica Martinello, was once a student of mine—nice to be in such fine, poetic company!

What’s especially gratifying is the poem selected by Columba‘s editor, Emily Tristan Jones, “Poetry, here, meaning: whatever language helps you sleep at night,” a kind of breathless, dithyrambic work, long a favourite compositional mode of mine, but one ever less frequently indulged.

You can read that poem, and all the others in this Fall edition, here.

Shelf Portrait

The good folks at The Richler Library Project at Concordia University have shared my “Shelf Portrait,” a brief piece on my home library. The essay ranges over the contents, organization, and use of my books and includes a few, choice pictures.

One addendum, mind you: the photo of a sample of my ufological library, is hardly of “Works on cosmicism, astrology[?!], and space exploration, among other celestial subjects“!—It’s all about UFOs and related matters from a wide variety of angles!

You can read my Shelf Portrait, here. Why not browse all the others, here?

Much gratitude to Jason Camlot, scholar, poet, and musician, for soliciting the piece.

“Hell’s Printing House”: X Ore Assays (2001)

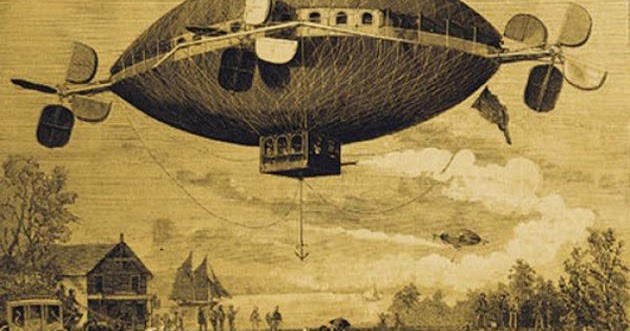

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

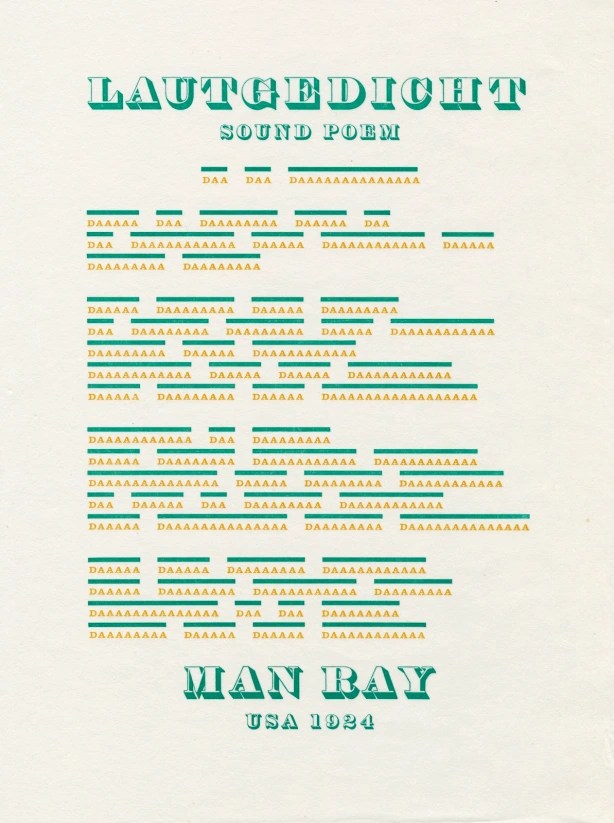

In 1998, I published my first trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems, which collected most of the poems in my previous chapbooks, other than those in On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (which can be accessed here under the ‘Orthoteny‘ tag). I continued to mine and open new compositional veins in line with what I had written, but embarked in a totally different direction in late 2001 with X Ore Assays, which takes inspiration from a number of sources. The most immediate is FEHHLEHHE (Magyar Műhely, 2001) by the Hungarian musician, archivist, editor, writer, and cultural worker Zsolt Sőrés. FEHHLEHHE deploys a wide, wild range of linguistic disruption: disjunctive syntax, polyglottism, collage, sampling, homophony, and portmanteau words, among other means. X Ore Assays is in part an attempt to engage Sőrés’ text in kind, wrighting an English that would imaginably answer his Hungarian. A more remote but profounder influence is the homophonic style that myself and the late Dan Philip Brack (DPB) corresponded in, portions of which were intergrated into his series of short prose works, Letters from Jenny. In our correspondence, very few words were spelled in anything other than a pun, a delirious, funny, private literature, a practice whose linguistic energy I desired to tap in composing the project whose working title came to be X Ore Assays. An even deeper inspiration was the surreal practice of William Burroughs in writing “the word hoard” that was reworked and worked up into his breakthrough novels Naked Lunch, Interzone, The Soft Machine, The Ticket that Exploded, and Nova Express. I aimed to cleave close as I could to that first definition of Surrealism: “Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation,” a much more fraught practice today than over two decades ago. The working title was motivated by this experiment: the texts, composed daily, would comprise a score (x-ore) of raw material (ore) to be assayed, measured, graded, and perhaps refined. However, a kind of ironic, poetic justice intervened. One of the days in this open-ended practice fell on September 11, inserting these texts radically and irretrievably in time’s flow. Curiously, that day was not immediately remarked; rather, hearing of, I think, Billy Collins’ refusal to write of the event almost a week later spurred, ultimately, fourteen more days of response, a supplemental sequence provisionally titled “Sewn Knot.”

That initial twenty, as a gesture of homage, I sent to Sőrés, who arranged to have them published in the Hungarian-language avant garde journal Magyar Műhely. “Sewn Knot” appeared, thanks to efforts of the editor-publisher of Broke magazine Andrea Strudensky, in the Canadian periodical dANDelion. “X Ore Assays” and “Sewn Knot” have presently been combined and are being revised and refined under the working title “after FEHHLEHHE,” which makes up the opening section of a manuscript-in-progress tentatively titled Fugue State.

The sections responding in real time to 9/11 were not among those included in the chapbook; they can, however, be read, here. I reproduce, below, a page from the middle of the book, and read the day’s work beginning “Wit noose Airecebo..”

Next month: Seventh Column (2001).

Crosspost: from Orthoteny: a work in progress: Magonian Latitudes

Here, I share a sequence of poems from my second trade edition Ladonian Magnitudes, “Magonian Latitudes,” which, among other things, relates tales from the Middle Ages of Sky Ships and their crews and their interactions with mortals. You can read—and hear!—the poetic sequence, here.

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: closing cantos

Here I link to the closing cantos of a long section On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery from a long work on “the myth of things seen in the skies,” Orthoteny.

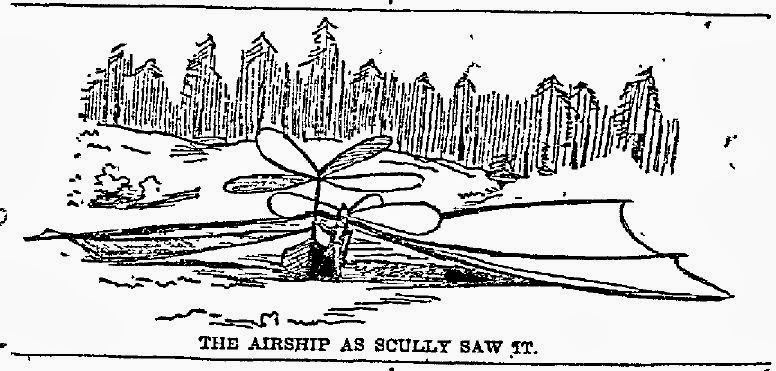

Following the Mystery Airship flap of 1896/7, as real airship technology slowly took off, sightings of what seemed airships continued globally. These airships, however, were observed to outperform their real counterparts in inexplicable ways.

In the days leading up to the Great War, sightings of airships, understandably, increased. They later appeared, this time all-too-much for real, over London, in the world’s first aerial bombardment. And, just as as forerunners of UFOs were to appear in the skies over Europe and the Pacific as “Foo Fighters” in the Second War, the horrors of the Gallipoli campaign in 1915 were to inspire a myth of a mass abduction…

You can read, and hear, these three poems, here.

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April 18, 19, 21, 24, and 26

Here, the penultimate cantos from a section of a long work concerned with “the myth of things seen in the skies,” Orthoteny. These cantos relate phantom airship sightings, landings, meetings with their pilots, and debunkings from a prototypical UFO “wave” that occurred in April, 1897. These tales are of interest for including (among other things) the first report of a cattle mutilation and the story of an airship dragging an anchor, which echoes a tale from the Middle Ages!

You can read these poems, and hear them, too, here.

“statements, terms, and jargon”: Tuesday 17 October 2023

Time constraints and temperament restrict many of my thoughts to remarks. Thus, what follows are emphatically fragments, metonymies (parts) of potentially more-extended discourses and drafts (essays) holding the promise of future elaboration….

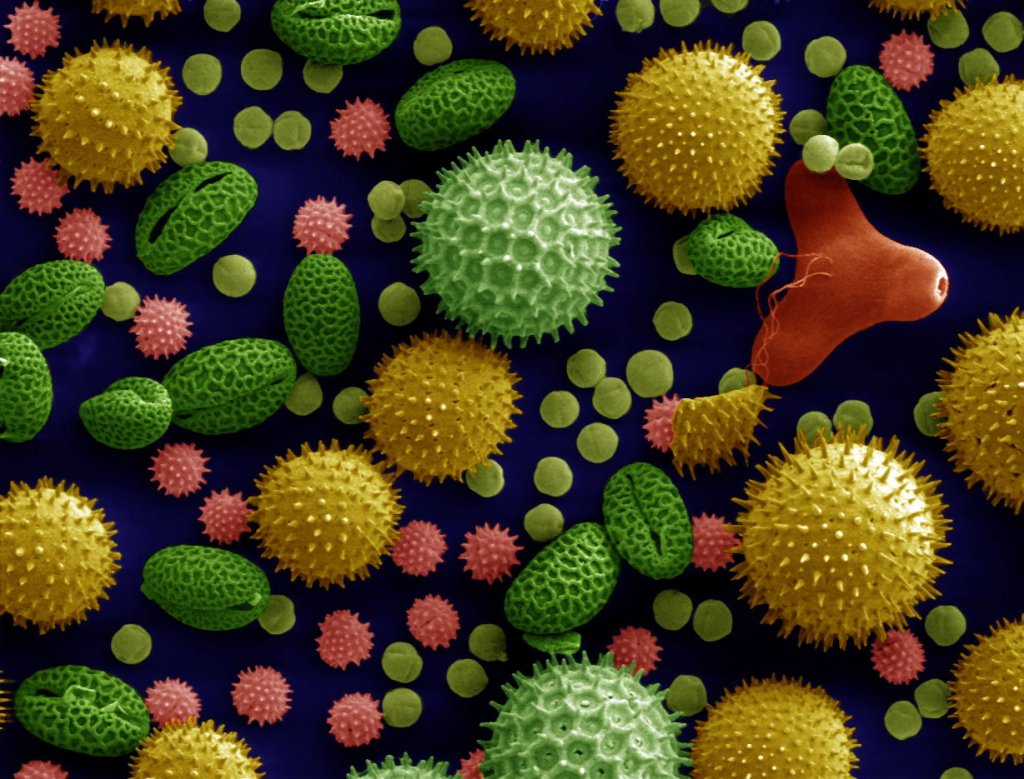

The debate over the origins of the coronovirus continues four years after the pathogen’s emergence. Whether the virus “leaked” from a lab or originated in a wet market is false dilemma, however. Gain-of-function research is carried out to help predict how virusses that originate “in the wild” might mutate and effect human beings; wet markets are precisely a vector for such virusses. At base, both sites are situated in a dysfunctional food production system “linked [as Hadas Thier puts it] to the rise of factory farming, city encroachment on wildlife, and an industrial model of livestock production.” Thus “the debate” is a distraction from the real, material conditions that gave rise to Covid-19 and that culture future pandemics…

Presently, Quebec’s civil service unions are negotiating a new contract with their “employer.” What is as remarkable as it is unremarked (such silence an index of ideology) is the adversarial stance adopted by the provincial government. It seems not to understand that a robust and efficient civil service is not an “expense” or “cost” to the province. An effective civil service would, first, deliver needed services to the population, which would culture a happier population, one would think, rather than one for whom life is made increasingly difficult if not downright precarious. And wouldn’t a governing party want a happier populace? But, moreso, an investment in the civil service is a cash-injection in the province’s economy, not a drain on the government’s monetary resources. In the first place, a non-trivial portion of wages and salaries are immediately recouped as income tax. What remains of the wages and salaries is, for the most part, spent on local goods and services (and the resulting profits are themselves subject to taxation). If the civil servants are fortunate enough to have any surplus monies (a majority of Canadian households run a debt), those funds are deposited in local financial institutions, banks or, ideally, credit unions, which, then, in turn, are leant out as a further cash injection into the province’s economy. And what is most egregiously overlooked is that the province’s civil servants are themselves tax payers—that group always appealed to to keep governments’ “operating costs” low—and most importantly citizens.

“Populism is always ultimately sustained by the frustrated exasperation of ordinary people, by the cry, ‘I don’t know what’s going on, but I’ve just had enough of it! It cannot go on! It must stop!’ Such impatient outbursts betray a refusal to understand or engage with the complexity of the situation, and give rise to the conviction that there must be somebody responsible for the mess—which is why some agent lurking behind the scenes is invariably required.”—Slavoj Žižek, First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (New York: Verso, 2009), 61.

If the shock of the Great War and attendant traumas drove many to choose between fascism and communism, liberal democracy and capitalism having been revealed in their essential bankruptcy, then how much moreso now with the Pandemic and the Climate Emergency? And what of the insight that liberal democracy is and has been merely the vehicle of the political power of the bourgeoisie? That the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions and the demise of Feudalism and monarchy all accompany the advent of Capitalism, that that development is “modernity”? Then, how fateful the name of “the Occident”!

A fateful analogy: “The commodity, a singular concept, has two aspects. But you can’t cut the commodity in half and say, that’s the exchange-value, and that’s the use-value. No, the commodity is a unity. But within that unity, there is a dual aspect.”—David Harvey, A Companion to Marx’s Capital (New York: Verso, 2010), 23.—The sign, a singular concept, has two aspects. But you can’t cut the sign in half and say, that’s the signifier, and that’s the signified. No, the sign is a unity. But within that unity, there is a dual aspect….

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April the 17th, Aurora

Here’s the next instalment from a part of a long poem Orthoteny dealing with “the myth of things seen in the sky,” an episode from the Mystery Airship wave of 1896/7, here an archetypal UFO crash. You can read it—and hear it!—here.

Resist, much?

It was and remains an aesthetic, critical, compositional commonplace in some circles that the poem that resists ready understanding resists the capitalist order that would reduce all things to readily consumable commodities.

There are, of course, at least caveats to this position. No text, however transparent, is ever absolutely so, or it would be invisible. That is, all language is possessed of an aesthetic aspect (phonic, graphic, or tactile) as a condition of its possibly serving as a communicative or aesthetic medium at all; its materiality is inescapable. Moreover, no poem can possibly give over its reserves of meaning. “The words on the page” (to invoke a hoary critical paradigm), under sufficient scrutiny, betray an interpretive wealth far in excess of their immediate, prosaic, “literal” meaning. Even more, as a text, the poem is woven from and thereby back into other discourses; it is implicated in a very complex way in its culture. Furthermore, being a temporal phenomenon, that is, existing through time, this con-text will vary; being “fatherless,” the poem will be variously resituated, recontextualized, by ever new readers and thereby made to resonate in new, unforeseeable and uncontrollable ways. And one would be remiss to not remark most critically that it is not the poem that is, strictly, commodified, but what contains it, the book, periodical, or website; the poem is not consumed, per se, but the “thing” that packages it, which is bought and sold.

To these reflections, Abigail Williams’ Reading It Wrong: An Alternative History of Early Eighteenth-Century Literature seems to add a new angle. As the publisher’s description relates,

Focussing on the first half of the eighteenth century, the golden age of satire, Reading It Wrong tells how a combination of changing readerships and fantastically tricky literature created the perfect grounds for puzzlement and partial comprehension. Through the lens of a history of imperfect reading, we see that many of the period’s major works—by writers including Daniel Defoe, Eliza Haywood, Mary Wortley Montagu, Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift—both generated and depended upon widespread misreading. Being foxed by a satire, coded fiction or allegory was, like Wordle or the cryptic crossword, a form of entertainment…

Williams’ argument is compelling in at least two ways. First, her sample texts’ being resistant to understanding is precisely their appeal, their “selling point.” Second, the horizon of this elusive, allusive aesthetic is the early morning of capitalism in England, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, a famous index of the ideology of the moment. However, 2023 is not 1723, however much both are determined by a shared social formation, nor is the superstructure of these two moments the same. (Habermas’ forthcoming A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics is all the more looked forward to in this regard). Nevertheless, Williams’ study complicates the still vital, urgent demand to think about the place and function of poetic language in our present, critical moment….

Comments (2)

Comments (2)