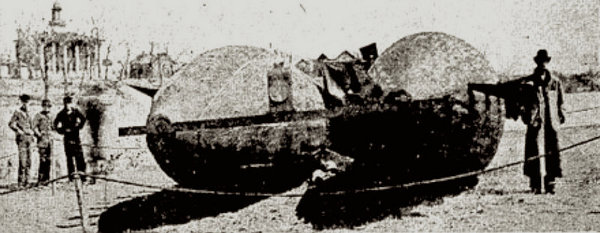

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, April 12-16

Here, the next instalment of ten cantos more from a poem about an archetypal moment from that “myth of things seen in the skies,” a prototypical “UFO flap” from April, 1897, again, with a newly-made recording…

AN OMNIPOETICS MANIFESTO, from PRE-FACE TO A HEMISPHERIC GATHERING OF THE POETRY & POETICS OF THE AMERICAS “FROM ORIGINS TO PRESENT”

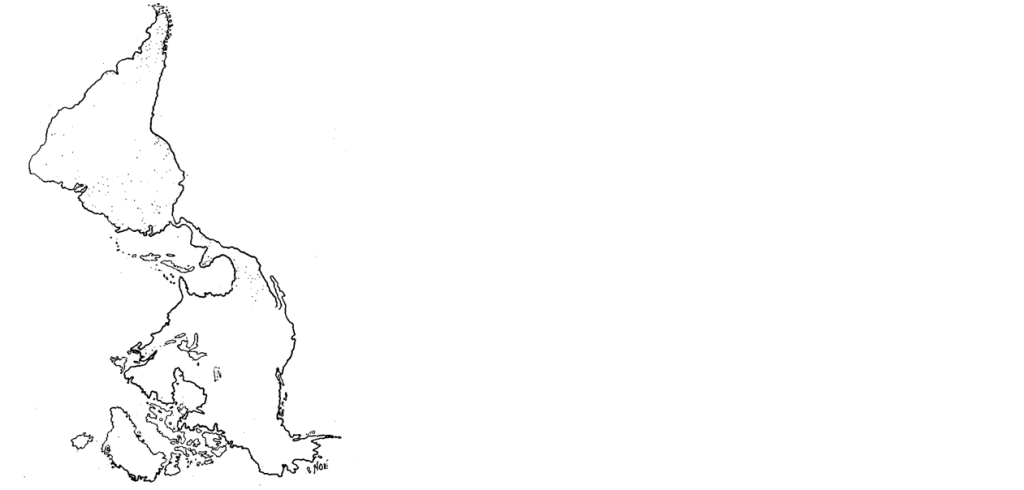

I share here an excerpt from the Pre-face to Rothenberg’s and Taboada’s forthcoming assemblage of poetry and poetics from the Americas, from origins to the present. Not only is the omnipoetics manifesto therein of overriding interest in its own right, but Rothenberg’s and Taboada’s anthology also includes a translation from Louis Riel’s Massinahican by Antoine Malette and myself, some of which can be read, here.

The post, first published 4 October 2023, at Rothenberg’s Poems and Poetics blogspot can be read, here.

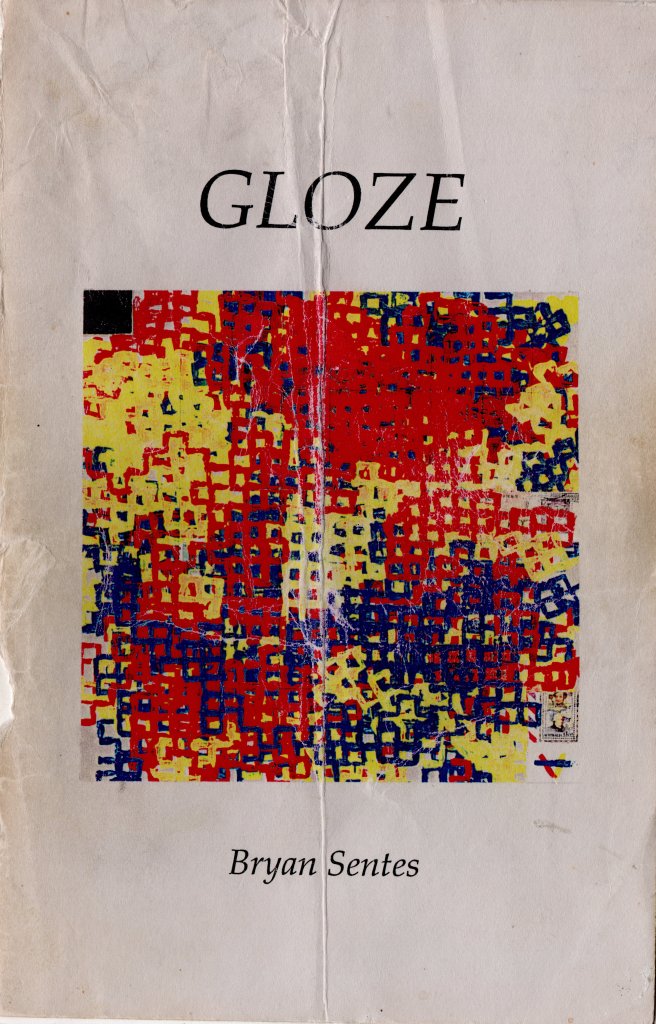

“Hell’s Printing House”—Gloze (1995)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Gloze is my first self-produced, self-published chapbook, inspired by Pneuma Press’ Budapest Suites. As I note in the prefatory remarks to this series of posts, Gloze and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery were the works that represented me during my European Tour of 1996 and for some years after, until the publication of my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central and other poems in 1998. The cover is an original artwork of my own, an aleatoric painting in acrylic and collage.

Contents

- Grand Gnostic Central

- After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort

- Smalltalk Hamburg 91

- Two

- Three

- In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14

- DP Channels Baba G

- Arachnophobia Prima Facie

- Five

- Thou, Palæmon

- Transcription

- Six

- “As I delighted with the enjoyments of torment…”

- Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli

- Otto (1)

- Á Québec

- ‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath

- Horizontal Gold Golden Mercury

- Tonight

- Green Wood

- Ten

- Marmitako

- Will of the Wisp

- Coda: Gloze

“Grand Gnostic Central” is, here, five prose poems (one of which can be read here) and the poem “Tonight, the world is simple and plain.” All poems hyperlinked above are “published” on Poeta Doctus; “Gloze” is represented by a YouTube rendition by “Jake the Dog.”

Although I had yet to publish a full-length trade edition, the poems collected in Gloze already gather work representative of a decade’s work and engagement with the poetry of my peers. At least the prose poem about Wittgenstein and the poem beginning “Tonight, the world is simple and plain…” along with that engaging Meister Eckhart (“After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort”) were composed during my graduate studies (1986-89), when I was labouring to write a way between and with poetry and philosophy, the topic of my master’s thesis. Nevertheless, my concerns were hardly exclusively abstruse: “Smalltake Hamburg 91″ addresses racism,”Thou, Palæmon” the first Gulf War, and “Á Québec” québecois nationalism. As down-to-earth, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury” and “Marmitako” ruminate on the alchemy and joy of preparing our daily bread. At the same time, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury,” with its allusion to alchemy and the Hermetic philosophy, betrays an interest in more recherché matters, whether the psychicomagical experimentation of Willliam Butler Yeats (“Otto (1)”) or ghost stories from my grandparents’ generation (“Will of the Wisp”), whose Hungarian side are given a nod in the poem “‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath,” no less a satire of, again, ethnonationalism. “DP Channels Baba G” is a terse condensation of the life of a Hindu saint, a gesture toward an attention to more “spiritual” matters, a leitmotif in much of my poetry. “Arachnophobia Prima Facie” is more psychological, exploring a fear of spiders that reaches back to my earliest memories. “In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14” is a humorous poem about poetic influence and stature.

But, apart from such thematic concerns, many of the poems are more overtly formal, compositional or artistic in their motivations. As I remark with regards to the poem “Six”:

Back in the early Nineties of last century (!) when I wrote this poem, the fashion among many Canadian (at least) poets was to write sonnet sequences. By chance, one day, I wrote a poem (“I know the Aurora Borealis” in Grand Gnostic Central) that happened to have fourteen lines. That chance (which to my ear happily rhymes with ‘chants’) occurrence began an ongoing, half-satirical series of accidentally-fourteen-line poems I called variously over the years “soughknots” (literally “air-knots”) and here “sonots” (so not sonnets!).

All the numbered poems are such sonots. Aside from the prose poem about Wittgenstein in “Grand Gnostic Central,” the others are inspired by early ‘pataphysical prose poems of Chris Dewdney’s. “Transcription” is a sequence of improvisations, likely motivated by an engagement with the spontaneous poetics of the Beats, which I had studied intensively during a memorable summer course in my graduate studies. “Tonight” pretends to this mode, but frees itself from it by means of a litotic irony turning on the ambiguity of a pronoun. “As I delighted with the enoyments of torment…,” “Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli,” and “Gloze” are all experiments in collage poetics. “Gloze,” especially, is a formal innovation of my own, prompted by the Wittgensteinian dictum that “meaning is use.” “Gloze,” and other poems, collate all the meanings of a word or phrase and represent them cubistically by means of the examples provided by the Oxford English Dictionary…

Of all the poems in Gloze, I’m most moved to share “Green Wood,” a poem that synthesizes much of the influences and experiments present in the book. On the face (and “ear” of it), it is reminiscent of the rhapsodic poetry of Allen Ginsberg and others. However, it’s opening line nods to a more radical influence, a translation from Lucretius by Basil Bunting. However much it might be said to deal with personal experience, it tends toward a more objective, metonymic, paratactical presentation, and is guided by a shy, mystical sensibility, perhaps most visible in its attention to synchronicities. Below, you can hear recordings of that poem, along with a performance of Bunting’s translation, a poem I was given to recite at the beginning of my poetry readings at the time.

“Green Wood”

Bunting’s Lucretius’ “Hymn to Venus”

Next month, X Ore Assays (1st Score), 2001:

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April, 1, 2, 9, and 11

Here, the next instalment from my long poem probing the “myth of things seen in the skies,” the opening cantos from the most important section from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, “April,” complete with recording!

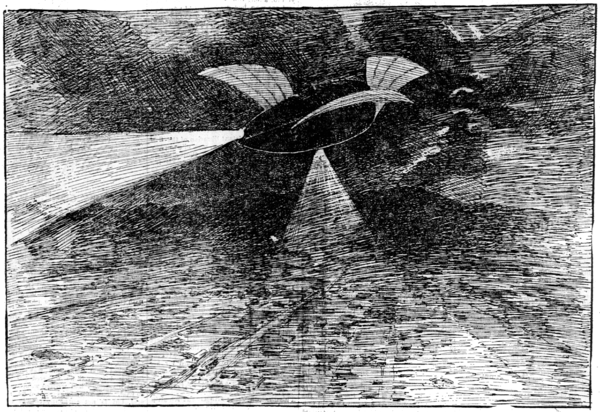

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: “The Phantom Air Ship”

I share here the latest instalment over at Skunkworksblog of part of a long, work-in-progress, a poetic treatment of the “myth of things seen in the skies.” This latest post is another part of the chapbook On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery that treats a prototypical “UFO wave” avant le lettre during the years 1896/7. You can read—and hear it!—here.

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, Prelude

Here’s the next instalment of the epic work-in-progress about the “myth of things seen in the skies.” This week, the Prelude to the most complete part of the project, a poetic recounting of an archetypal “UFO flap” over mainly the continental U.S. in 1896/7. You can read—and hear it!—here.

Cross post: from Orthoteny, a work in progress…

Apart from what goes on here at Poeta Doctus, there’s a whole other side to my poetic, cultural work, I reveal only to a select readership. There, for longer than I care to admit, I’ve been labouring on a long work on what Carl Jung termed “a modern myth of things seen in the sky.”

I’ll be posting parts of that epic-in-process, whose working title is Orthoteny, along with a recording of a new reading of that part, weekly, for the foreseeable future.

You can read the first post in this new series, here.

Irritability is a sign of life…

IRRITABILITY: the property of protoplasm and of living organisms that permits them to react to stimuli.

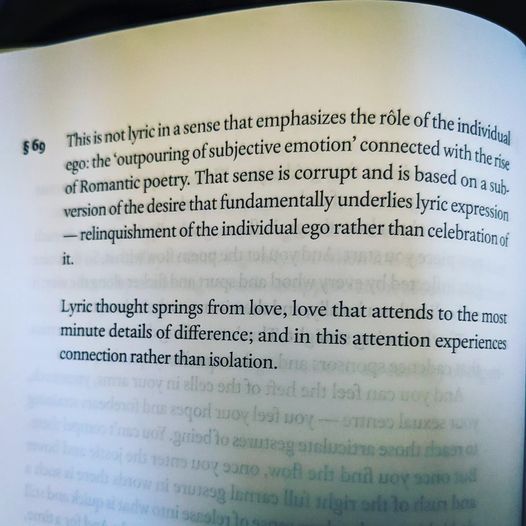

Poet (and a quite respectable poet I might add) Ralph Kolewe shared the above passage and caption this Labour Day. That it irritated me is an understatement…

That opening paragraph, with its allusion to “the ‘outpouring of powerful emotion’ connected with the rise of Romantic poetry” will twig with those readers who remember a time in the not so distant past when, imaginably as a reaction to what was perceived to be a persistent, pernicious poetic, it was de rigueur to set up a Straw Man Wordsworth as responsible. Zwicky’s wording is brow-furrowing, for it suggests that either she has misremembered Wordsworth’s actual words from the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads (“For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings…”) or that she has formulated a parody of them to gesture toward that modern tendency she has in her sights, a tendency a faint echo of the Romantic thunderclap. Surely, the more charitable reading is the latter, but then the weakness of what she would negate infects her position: how strong can it be if it needs set itself over against a mere parody of its much more sophisticated and robust progenitor?

Just what poetic tendency, then, does Zwicky have in her sights? The answer to this question likely lies in the 301 other remarks and their parallel running text of quotations that compose Lyric Philosophy, the book Kolewe quotes. I must admit, scrutinizing the cited passage isn’t very helpful: this “corrupt” sense of lyric “emphasizes the rôle of the individual ego” in an “‘outpouring of powerful emotion’,” a sense “based” on a “celebration” rather than “relinquishment of the individual ego,” an emphasis and celebration that presumably results in “isolation” rather than “connection.” Some poetry from the past six or seven decades might come to mind, but the search leads away, ultimately, from the lyric sense Zwicky would affirm, and its own, not unproblematic Vorurteilen (prejudices or presuppostions…).

First, what sense of ego is operative here? Is it the Cartesian cogito, the transcendental subject of Kant or the “I am” that accompanies all thought, or the transcendental ego of Husserl, or the ego of psychoanalysis or analytic psychology? Is it some pedestrian understanding of the individual self, or even a particular inflection of the lyric “I,” that endlessly problematic persona? An answer may lie in the context of the work from which the remark is abstracted.

More gravely, however, the thinking here seems to overlook that longstanding “relinquishment of the individual ego” in modern and even “archaic” poetries. Certain strains of avant garde poetics, from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, to the chance generated poems of John Cage and Jackson MacLow, along with William Burrough’s “Third Mind” poetics, back to Charles Olson’s “objectism” (and his explicit criticism of the place of the ego in Ezra Pound’s Cantos), the practice of the Objectivists, or the impersonality advocated by the early Eliot, or even Yeat’s masks all questioned or sidestepped the primacy of that individual ego. One could extend this line back even to the “I” in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ernesto Cardenal’s exteriorismo and Pessoa’s (and Canada’s Erin Mouré’s) heteronyms come to mind. The poetics of French Surrealism and Mallarmé’s poetry or a particular reception of Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” are apropos. And what of that obscure “I” crystallized in autobiographical shibboleths in Celan’s later poetry? More radically, even a cursory reading of Jerome Rothenberg’s assemblage Technicians of the Sacred reveals a global range of poetries, communal, divinatory, shamanic, and otherwise that spring from sources and concerns other than “the individual ego.”

My point here is not to contradict Kolewe’s enthusiasm or set Zwicky up as a Straw Person, but rather to register a particular impatience with reflections on poetics that gaze into too shallow a small pool. Poetries that sing something other than an individual self are legion. All of which leaves aside for the moment the question of the grounds for and imaginable value of a lyric practice that dwells on and in an I, if not celebrates it. Perhaps blame lies with that first modern poet, Dante Alighieri, and his making at least three aspects of himself and their poetic and eternal fate the subject of his Commedia…

“Hell’s Printing House”—Budapest Suites (1994)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Budapest Suites is the first published version of the titular poetic suite that later appeared, slightly revised, in my first, full-length trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems (1998). It, along with all books issued in the Pneuma Poetry Series, was designed and printed by my friend Richard Weintrager.

Contents

- “Apply what you know to what you feel that’s more than enough”

- “Mount Ság”

- “That he might…”

- “The chest-high white-haired Swiss woman asked…”

- “I went down to Bibliomanie”

- “Dan and I waltzed hopfrog…”

- “You don’t just follow an impulse do you?”

Budapest Suites collects poems written during and after a 1991 trip to Europe (my first!), whose highpoint was a visit to Budapest and Celldömölk, the hometown of scholar poet friend Kemenes Géfin László, there to be honoured for his literary work and to launch his avant garde epic work Fehérlófia (the son of the white horse). On that occasion, we visited the extinct volcano on the outskirts of town Mount Ság (Sághegy) where Géfin had hidden out during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 before escaping over the border to Austria. Géfin was struck by the lushness of the locale, so much he was moved to remark, “There is a god here!”, the opening line of the second suite.

In Budapest, I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of some American ex-pats, among them, writer Dan Philip Brack (DPB), “Dan” in the opening line of the penultimate suite. Let’s attribute the epigraphs of the first and last suites to him. The fourth suite commemorates a visit to the National Museum. The third suite, as well, was written in situ. The fourth suite was composed after returning to Montreal; its being slightly confusing might be attributable to its being “a mystical poem,” as Hungarian poet Tibor Zalán called it.

The poem recorded below is the third suite. Darius Snieckus, author of the inaugural chapbook in the Pneuma Poetry Series, The Brueghel Desk, was so impressed when he read it, he insisted I not “change a thing!”. His anxieties were not unfounded, as up to and into the writing of the Suites, I had been an obsessive reviser: I still have the notebook with the seventeen (at least) versions of “Mount Ság” worked over that one afternoon, including the Hungarian translation by Zalán and András Sándor, which was read to Géfin on site in honour of the visit.

It was in revising the fourth suite that the most recent, nth version turned out to be identical to the very first. It was then I learned the truth of William Blake’s dictum “First thought best in Art…” From that revelation on, my compositional practice was to write, then carefully study what had been written to understand its spontaneous rightness before cautiously making slight alterations, only in order to bring out the energy of that original impulse all the better. It was Joachim Utz, one my most careful German readers, who noted that the Budapest Suites marked a “breakthrough” in my poetry.

Next month, Gloze (1995)…

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment