Announcing “Hell’s Printing House”

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

First up, Budapest Suites (Pneuma Poetry Series, 1994)…

“statements, terms, and jargon”: Saturday 2 September 2023

Time constraints and temperament restrict many of my thoughts to remarks. Thus, what follows are emphatically fragments, metonymies (parts) of potentially more-extended discourses and drafts (essays) holding the promise of future elaboration….

“If you want to change your life / burn down your house…” These words, which open Peter Dale Scott’s Minding the Darkness: A Poem for the Year 2000, strike an uncannily, untimely note in light of this season’s fires in Maui and in Canada’s north and west coast. The first canto of Scott’s long poem describes experiencing one of the no-less devastating wildfires Californians suffered in the closing years of last century. Both the fires in California and Maui left “rivulets of metal // from… melted cars.” From a broader, historical perspective, my German father-in-law, who came of age in the closing years of the Second World War in Germany’s industrial zone, the Ruhrgebeit, when he saw pictures of the devastation in Maui, was reminded of similar pictures he’d seen of a bombed-out Dresden. Such devastation, that stretches back, too, to that of the Great War, prompts Scott to cite Heidegger’s 1929 study, Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, concerning “Dasein face to face // with its original nakedness.” Have we here, perhaps, a new literary topos?…

Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, do not write but, more exactly, perhaps, merely generate not even intertext but a permutation of its elements (words). Where intertext, rigorously, is “scraps of text that have existed or exist…the texts of the previous or surrounding culture… a new tissue of past citations…”, the “wake of the already-written”, what LLMs produce is only the most probable order of words. Do such prototexts not, imaginably (if not imaginatively) call forth, then, from poetry a countermeasure, the demand to compose in the least likely syntax? This demand transcends The New Sentence, wherein parataxis occurs only between sentences, urging a rereading of not only those most syntactically centripetal L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poems, for example, but those explorations in this direction in, among others, the novels and poems of William Burroughs and John Cage, let alone those even older, deeper efforts to evade, avoid, or otherwise complicate the declarative sentence as “a complete(d) thought” in the poetry of Charles Olson, Ezra Pound, and William Carlos Williams, among so many others.

Or, from a related angle, chatbot “poems” need be considered in light of earlier modes of aleatoric composition, whether Burroughs’ Third Mind techniques or Cage’s or MacLow’s employment of the I Ching, or, farther back, Surrealism and Dada, or, even more radically, the various forms of divination throughout space and time, such as those collected in Jerome Rothenberg’s Technicians of the Sacred and remembered even in the classical heritage of antiquity (the Sybil’s leaves…). Given that the unconscious if not the “mindless” has been overtly and consciously employed in the composition of poetry to a variety of ends, chatbot “poems” or their precursors (which go back decades) are hardly “new.” Indeed, their very place in so-called “Late” Capitalism urges their scrutiny in light of the tradition, especially when they are employed “to write” “poems.” Is it inconsequential that Breton was a communist, that MacLow and, in his own way, Cage were anarchists?…

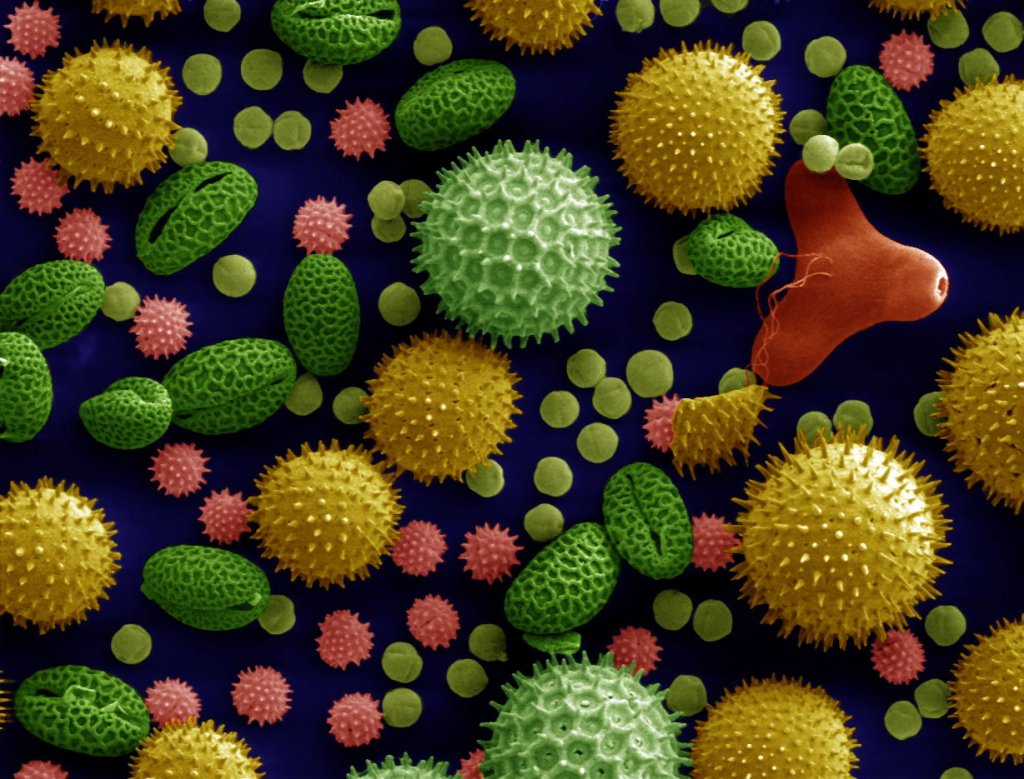

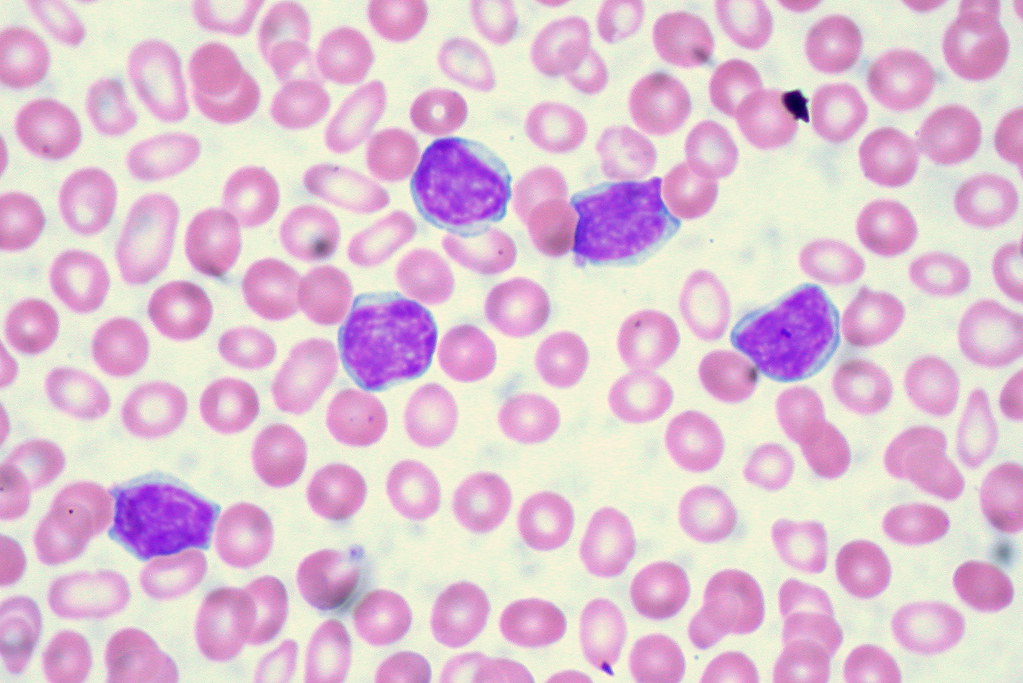

Perry Anderson, in his Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, sketches the grounds for “The General Crisis” of the Fourteenth Century. On the one hand, agricultural production reached a limit: existing, arable land was becoming degraded, and land that could be reclaimed had been and was of a poor quality. At the same time, silver mining could neither dig deeper nor exploit the relatively poor-quality ore that could be accessed, affecting the amount of coin in circulation. This crisis in the forces of production was aggravated by the Black Death, which killed an estimated net 40% of the population of Europe.

Parallels to our present day are suggestive. The carrying capacity of the earth’s ecology has been breached (however much we do in fact produce enough food to feed the world’s population; the problem is one of distribution), and we cannot in principle exploit existing fossil fuel reserves without burning down our own house. Covid is hardly the Black Plague, but it is only one of the pathogens that have been and will be released by the progressing economic colonialization of what wilderness remains.

Nevertheless, on the other side of the Fourteenth Century and its crises was not total collapse, but the Renaissance….

At a time of deep social fragmentation (Identity politics, ethnonationalisms…) and irrationality (a loss of consensus, determined by so many factors…) and no less in the face of the climate and more general environmental crisis is it not necessary, then, to revive the Universal and the Human?…

“To praise, that’s the thing!”

“Being a poet,” at least an anglophone poet in Canada, can seem sometimes near impossible. Sheer incomprehension and yawning indifference can drive one to despair, let alone those of us already perhaps too self-critical or reflective. At times, however, we may be fortunate enough to encounter those with heart enough to speak their appreciation for our work in our hearing. It was during one dark patch I called to mind those who had so praised me, remembering them in the following poem (which hopefully remains unfinished!).

D. M. Bradford’s latest: Bottom Rail on Top

Former student and present poet friend announces the imminent publication of his second trade edition, Bottom Rail on Top, “a kind of archives-powered unmooring of the linear progress story [that] fragments and recomposes American histories of antebellum Black life and emancipation, and stages the action in tandem with the matter of [the poet’s] own life.

You can hear the author say a few words on his new book and pre-order it by clicking on its cover:

Absolutely modern Romanticism

Welcome news from Jerome Rothenberg concerning a new initiative by Jeffrey C. Robinson, with whom he edited an essential assemblage Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: Romantic and Postromantic poetry.

Announced is a putative collection of “75 or so statements, terms, and jargon from the ‘Romantic mother-lode’ (Anne Waldman) with the hope that together, with accompanying commentary, they will accumulate irrefutably a major well-spring for modern and contemporary innovative poetry,” a collection that will prompt a “recognition of [romantic poetics] as a loose system of outlandish thought for the renovation of poetry in the service of a renovation of society.” Robinson highlights a handful of salient concerns (in his words): a new view of the world, sub specie aeternitatis; the not unrelated symbolic implications of Jacob’s Dream; the Fragment as Coherence over Unity and the Future; and a stance Against “palpable design”.

Romanticism, as a sensibility, but always too-much anchored to a concept of its being an historical period, has been resurgent, at least, since the reaction to the strictures of (at least, anglophone) literary Modernism (e.g., the criticism of T. E. Hulme, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) and the (ideological) aesthetic of the New Criticism. The poetics at work in the poetry of Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg and in the criticism of Harold Bloom, Geoffrey Hartman, and Paul de Man are well-known examples of this countermovement. However, first, with the scholary innovation of “constellation studies” and the resultant, rigorous reappraisal of Jena Romanticism and German Idealism (here, the names Dieter Henrich, Manfred Frank, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Andrew Bowie are exemplary) through the 1970s and 1990s served (at least among those paying attention) to utterly reorient the place and value of the thinking called “Theory” and the poetics and compositional practice that Theory influenced. Into this context, though with their own perspective on the matter and what’s at stake, step Rothenberg and Robinson with the above-mentioned assemblage (2009), the accompanying volume of poetics Active Romanticism (eds. Julie Carr and Jeffrey C. Robinson, 2015), and Robinson’s just announced project.

However much my own thoughts (and practice) are more or less in harmony with Robinson’s, there are points both of disagreement and concurrence. Coming of intellectual age studying Existentialism and Phenomenology (which, like Sartre, has led to an engagement with Historical Materialism) I’m leery of the invocation of the Spinozistic idea of viewing the world (and human life (and history)) sub specie aeternitatis (though, admittedly, Robinson does spin this notion in his own way). My aesthetic is very much, as I say, “ontological”, attending to what is given as the primary material, a nonjudgemental sensibility as phenomenological, Objectivist, “mindful”, or—as our romantic forbears (and descendants) put it, “prophetic” or “vatic”, an aesthetic that might well be said to be, in Robinson’s words, “forgiving.” In as much as such a stance is variously “estranging”, a literary value articulated by Novalis and Coleridge well in advance of Shklovsky, I am, again, in agreement. More philosophically (if not fundamentally), the view Robinson espouses here is in line with various posthumanist philosophical movements, such as Object Oriented Ontology (despite its antiKantian stance) and Timothy Morton’s not-unrelated Dark Ecology, the renewed interest in psychedelics, and other attempts to re-enchant the world, such as those of scholars Jeffrey Kripal, Jason Ãnanda Josephson Storm, and Marshall Sahlins, currents that pique my curiosity but no less my skepticism.

Robinson’s invocation of the fragment is welcome; my own poetics orbits the metonymical, which is essentially fragmental, in the Romantic sense. I find the futurity of the fragment demands more brow-furrowing; the optimism of writing for the future must, as, for example, much of the early writing of the Beat Generation did under the shadow of nuclear annihilation, be tempered by the very real possibility of cultural-historical foreclosure, the anxiety that has moved many young people from reproducing in the face of the threats of climate change…

What I find of most promise in Robinson’s proposals is his invocation of a poetics that eschews a “palpable design” (“We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us,” in Keats’ words). This approval might seem jarring in light of my invocation of the climate crisis and my admitted Historical Materialist sympathies, but anyone who has read, for example, Adorno’s essay on the drama of Sartre and Brecht “Commitment” will have a better idea of a writing without “palpable design.” Robinson invokes Vicente Huidbro, the Chilean poet of Altazor, “who locates palpable design as an intrusion of the ‘horribly official stamp of approval of a prior judgment (perhaps of long standing) at the moment of production’.” As Robinson glosses Huidbro:

Palpable design, while it may have been internalized, comes from without, from the social and cultural spheres, from “custom,” from the panopticon, from a voracious market economy with its association of any product, including a poem, with its acquisition, and from gender, race, and class inequities; it appears in poetry as received forms and received modes of speech that produces the familiar and consoling.

Here, Robinson’s writing of the fragment as a “pro-ject” invokes vital aspects of Olson’s Projective Verse as much as Nicanor Parra’s “anti-poetry” and the creative spirit and attendant strange novelty (creation) that runs from Dante, Cervantes, and Shakespeare (the Holy Trinity of the Jena Romantics) down to today. What is demanded by unprecendented times is an unprecendented poetry. Indeed, we live on a planet never inhabited by Homo Sapiens. What more radical call to make it new could be sounded?

What, then, is to be done?

Today, in reaction to the burning of over a hundred wildfires, thirty-six out of control, the province of Alberta has declared a state of emergency. Meanwhile, neighbouring British Columbia is suffering spring floods. And one doesn’t have to look too far afield to see the same and worse elsewhere (or elsewhen).

Understandably, among those persuaded of the reality of the threat of global warming and who either are not among those breathing hot and heavy over their growing fossil fuel wealth or haven’t simply given up (e.g., those persuaded of Near Term Human Extinction) the question of “What is to be done?” weighs heavy.

Among them are The Guardian‘s George Monbiot and scholar-activist Andreas Malm, the latter who has just published a rebuttal to a recent column by the former questioning the aptness of property destruction in the struggle for the system change the fight against global warming calls for—a good, provocative read.

Among those who pose the question asked above is myself, or, at least, the self who wrote the poem “And if I thought…” you can hear, below. (You can also read it at The /tƐmz/ Review here). I don’t offer any answers, but rather give vent to that sense of crisis, writing out of what that demand to act feels like, at least for me, then…

On Poets and Poetry, the Living and Otherwise

A line in a recent poem of mine reads, ‘”…Dante, Hölderlin, Whitman.” “They’re dead,” they said, an absolutely modern.’

The opinion, or, more charitably, judgement, of that “absolutely modern” is one I’ve encountered and that has irked me for nearly a generation (i.e., three decades) now. The well-read reader has likely already arrayed a phalanx of arguments to skewer said opinion, and I would hope the litotic irony that underwrites my line would serve as sufficient refutation, especially as, its being Easter weekend and I’m reading through the Commedia, “I have no will to try proof-bringing.”

That being said, a poem of mine published a while back in Scrivener, touches on, if not quite addresses, the topic. I offer it here, in print and voice.

I remain fairly persuaded this intervention is unlikely to be my final word on the matter…

New poems up at The Typescript

Though accepted last year, The Typescript has at long last published three poems that compose the tentative title track to my latest poetry manuscript, Blank Song (or maybe Amid a Place of Stone). You can read them, here.

Willow Loveday Little on James Dunnigan’s Windchime Concerto

Like, wow.

Very happy to share here a brief but no less impactful review/essay by one of Montreal’s—nay, English Canada’s—most exciting young poets on another no less exciting young poet.

You can snag a copy of Little’s first trade edition, (Vice) Viscera, here. Read her review essay here.

(Did I mention the folks at Yolk are doing great things?)

Five new poems in The /Temz/ Review #21

The /Temz/ Review has kindly published five recent poem of mine, along with poems, stories, and reviews by many others. You can read it all, here.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment