James Dunnigan’s Wine and Fire now available as an e-book

James Dunnigan is one of the most exciting young new poets I know writing today, a claim I make rarely.

Now, his chapbook Wine and Fire is available as an e-book for $5.00 Canadian, less than the cost of a pumpkin spice latte and a hell of lot sweeter and more nutritious!

You can see and hear Dunnigan read, below, and get your e-copy of Wine and Fire, here.

Chez Pam Pam: new volume from George Slobodzian

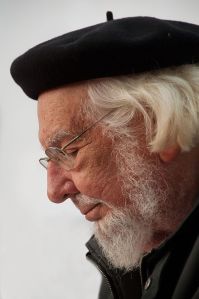

George Slobodzian, a poet-friend whose work I’ve admired and often lauded from the  start (over thirty years ago, now) finally has a new volume of poems out: a hefty forty-five-page chapbook Chez Pam Pam from Montreal’s Cactus Press.

start (over thirty years ago, now) finally has a new volume of poems out: a hefty forty-five-page chapbook Chez Pam Pam from Montreal’s Cactus Press.

For now, it’s readable only as an e-book (for all of CAN$5.00). I look forward to holding the physical volume in hand. In the meantime, you can whet your appetite for the real thing with Slobodzian’s poetry, which is, more importantly, the real thing.

“Now who is there to share a joke with?”

The words in this post’s title are Ezra Pound’s when he heard of T. S. Eliot’s death.

By chance, I was reminded that eleven years ago today, 10 June, a friendship of mine ended, one of that kind mourned by Pound at the loss of his friend.

Understandably, this friend, “Laszlo” in the poem, below, shows up in no small number of my poems, by various names. I share here this one, a joke, for those who might get the formal allusion, memorializing the last time he, I, and the third of our trio, all lived in the same city.

A sonnet is a moment’s &tc.

Laszlo, I wish you, and George, and I

were in that calèche, stalled in traffic,

left, McGill’s gate, Place Ville Marie right,

you flying to love in Holland. Straight out

Upstairs you hailed the passing, empty carriage.

We stopped at a dep George ran in for beer,

our cool québécoise driver declining

a draw or drink. Who can say why

she took the route she did, knowing you‘d

lived here forty years? Just, there we were,

Guiness sixpack shared around, a blue smoke

cloud coughing fit, riding high, our post-

Stammtisch Triangulation Finale

for all rush hour to see, invisible.

Condensation as Recomposition

Like many these days, I’ve been passing the time enjoying various televisual entertainments, most notably very carefully rationing out my viewing of Paolo Sorrentino‘s The Young Pope and The New Pope. Among these series’ many pleasures is the soundtrack, which introduced me to the British cellist and composer Peter Gregson.

Gregson, along with Max Richter, have both written what they term “recompositions”, Gregson recomposing Bach’s cello suites and Richter Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. Gregson’s and Richter’s reworkings are not without precedent: it’s an old compositional trick to take a phrase or theme from another composer’s music as an element for a new work of one’s own. These recompositions are, however, admittedly more radical and thorough reworkings of the original material.

In my own way, I’ve been writing recompositions for a long while.  One form, inspired by Pound’s found dictum that “dichten = condesare” (roughly, to write poetry is to condense), I termed “condensations”. The simplest compositional procedure, a manner of erasure avant le lettre, was to reduce a given text according to a rule.

One form, inspired by Pound’s found dictum that “dichten = condesare” (roughly, to write poetry is to condense), I termed “condensations”. The simplest compositional procedure, a manner of erasure avant le lettre, was to reduce a given text according to a rule.

The example I share below compresses H.D.’s book Sea Garden into a single poem, rendering each of the volume’s poems as a couplet made of the poem’s first and last line. I retained H.D.’s original capitalization and punctuation as a tacit way of indicating my recomposition was in a no way a unified, straight-ahead lyric poem. The results of this poetic compositional procedure strike me now as being very aesthetically similar to Gregson’s and Richter’s musical recompositions, which is why I share the poem “Sea Garden” from Ladonian Magnitudes, below.

Sea Garden

after H.D.

Rose, harsh rose,

hardened in a leaf?

Are your rocks shelter for ships—

from the splendour of your ragged coast.

The light beats upon me.

among the crevices of the rocks.

What do I care

in the larch-cones and the underbrush.

Your stature is modelled

for their breadth.

Reed,

To cover you with froth.

Whiter

Discords.

Instead of pearls—a wrought clasp—

no bracelet—accept this.

The light passes

and leaf-shadow are lost.

I have had enough.

Wind-tortured place.

Amber husk

as your bright leaf?

The sea called—

The gods wanted you back.

Come, blunt your spear with us,

And drop exhausted at our feet.

You are clear

of your path.

The white violet

frost, a star edges with its fire.

Great, bright portal,

still further on another cliff.

I saw the first pear

I bring you as an offering.

They say there is no hope—

and cherish and shelter us.

Bear me to Dictaeus

and frail-headed poppies.

The night has cut

to perish on the branch.

It is strange that I should want

as the horsemen passed.

You crash over the trees,

a green stone.

Weed, moss-weed,

stained among the salt weeds.

The hard sand breaks,

Shore-grass.

Silver dust

in their purple hearts.

Can we believe—by an effort

their beauty, your life.

A Sonot at Easter: “Come out of the cave…”

Back in the early Nineties of last century (!) when I wrote this poem, the fashion among many Canadian (at least) poets was to write sonnet sequences. By chance, one day, I wrote a poem (“I know the Aurora Borealis” in Grand Gnostic Central) that happened to have fourteen lines. That chance (which to my ear happily rhymes with ‘chants’) occurrence began an ongoing, half-satirical series of accidentally-fourteen-line poems I called variously over the years “soughknots” (literally “air-knots”) and here “sonots” (so not sonnets!).

Its being Easter Sunday brought to mind the opening line and title of another sonot from Ladonian Magnitudes, “Come out of the cave…”, a poem marked by if not marking the emergence of sociality with the warmer days of spring. Of course, now, with the social distancing imposed by Covid-19, getting out into the warmer sunshine is more delayed than it was in 1992, but, then, the poem wanders through art and memory, too, where we can all sojourn until we emerge from this present staid-of-emergency.

“Come out of the cave…”

Come out of the cave

Spring’s first cold night

After an afternoon on the Thing with George

Embryons desséchés and six Gnosiennes, followed by Sonatine bureaucratique and Le Picadilly in the air

This time the third

I think of the natural periodical ecstasy

We call sleep

And consequently dream

Washing and drying the dishes

After the red cabbage, letcho, and potatoes sour-style

Everything put away in place for tomorrow

I pour the hot milk into the yoghurt jars

Remembering measuring solutions in Chemistry

Certain of the results

For the love of Dante

Every Easter I read through Dante’s Divine Comedy, and when I’m teaching, the Inferno holds centre spot in a course I try to give every Winter term, “Go to Hell!”.

That love for Dante and the Commedia makes its way into my poetry, too. A reader sensitized to this fact will fill a big basket of easter eggs reading through my books, published and unpublished.

Rarely, my love for his work is expressed outright, like in this short poem, “The book I can’t read closed beside me…”, that you can hear, here:

Of course, you’ll get even greater pleasure reading through the Commedia outloud over Easter week: the Inferno, Good Friday through to Easter Sunday morning; the Purgatory, from Easter Sunday to Easter Wednesday; then begin the Paradiso Easter Thursday and ascend at your leisure!

You can hear the Commedia in Italian and English translation, at the Princeton Dante Project, here.

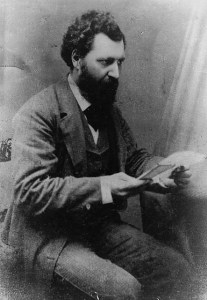

from The Massinahican by Louis Riel

Today, Antoine Malette and I are happy to share with you the first English-language translations from Louis Riel’s Système philosophico-théologique, part of a larger, incomplete work, the Massinahican.

In May 2018 I was lucky enough to be in Regina for the launch of Tim Lilburn’s The House of Charlemagne. He shared with me his enthusiasm for this obscure work, parts of which he had worked into his latest book. As Jerome Rothenberg had just recently put out a call for contributions to his latest project, an assemblage of poetry and poetics from the Americas, pre-contact to the present, Lilburn and I heartily agreed Riel’s Système should be represented.

You can read some of what we translated, selected by Jerome Rothenberg as part of his project, with a very brief commentary, at Jacket2.

What follows are some reflections on the task of the translators, then our original draft of a commentary, lengthier than is practicable for the forthcoming anthology, with a short selection from Tim Lilburn’s The House of Charlemagne.

This particular text poses challenges both general to Riel and particular to the Système.  Apart from those we remark (below), Riel’s French is, first, that of Nineteenth century Manitoba and Québec. It is, as well, formed by Riel’s education in Montreal: he studied, for example, no French literature past Racine, and his vocabulary and thought rest, in part, on the technicalities of the philosophy (e.g., Leibniz) and theology he read, as well as his understanding of the natural sciences (including electromagnetism) and arguably even the Theosophy of his day. Clearly, a ready acquaintance with this discursive field (which we admittedly lack) would go a long way to both comprehending Riel’s meaning and then attempting to render it in English (which, would, in turn, demand an acquaintance with the parallel literary, philosophical, theological, scientific, and Theosophical vocabulary in English). Finally, Riel’s was an idiosyncratic mind, both because of his universally-acknowledged intelligence and his equally acknowledged religious mania. Thus, the discourses named above were submitted to a stylistic pressure that resulted in the provisional, often highly-elliptical and truncated fragments (however original) that make up the Système. No less importantly, the Métis dimension in his thinking and expression remains extremely obscure, even for scholars of the man and his work.

Apart from those we remark (below), Riel’s French is, first, that of Nineteenth century Manitoba and Québec. It is, as well, formed by Riel’s education in Montreal: he studied, for example, no French literature past Racine, and his vocabulary and thought rest, in part, on the technicalities of the philosophy (e.g., Leibniz) and theology he read, as well as his understanding of the natural sciences (including electromagnetism) and arguably even the Theosophy of his day. Clearly, a ready acquaintance with this discursive field (which we admittedly lack) would go a long way to both comprehending Riel’s meaning and then attempting to render it in English (which, would, in turn, demand an acquaintance with the parallel literary, philosophical, theological, scientific, and Theosophical vocabulary in English). Finally, Riel’s was an idiosyncratic mind, both because of his universally-acknowledged intelligence and his equally acknowledged religious mania. Thus, the discourses named above were submitted to a stylistic pressure that resulted in the provisional, often highly-elliptical and truncated fragments (however original) that make up the Système. No less importantly, the Métis dimension in his thinking and expression remains extremely obscure, even for scholars of the man and his work.

We outline these philological challenges to highlight the radical provisionality of our own efforts here. Just as the sheets collated by Riel’s editor are “a draft of a draft of a draft” (Melville)(a characteristic this text shares with, among others, Leaves of Grass, Moby Dick, the writings of Marx, and many Twentieth-century poets and philosophers), so, too, our versions lay no claim to finality, but, rather, are offered as an invitation to readers, writers, and scholars and translators more informed and talented than us to engage with Riel’s Système so that it might begin to take its rightful place in the cultural inheritance and life of Turtle Island.

Notes toward a Commentary…

Source: The Collected Writings of Louis Riel, Vol. II, ed. Gilles Martel, University of Alberta Press, 1985, pp. 387-99. Translated by Antoine Malette and Bryan Sentes.

Poet, politician, rebel, prophet, Louis Riel is as much an inspiration for anti-colonial struggle on Turtle Island, politically and artistically, as a real man, the facts of whose life are easily summarized. Born of Métis parents in present-day Manitoba, Canada, the precocious Louis was sent to study for the priesthood in Montreal from 1858-1865, where he received a rigorous education in Greek, Latin, theology, philosophy, and literature. Choosing a secular life, however, he abandoned his studies and returned home, where he participated in the Red River Resistance (1869-70), as the head of the provisional government and overseeing the short-lived regime’s one execution. Following the insurrection, he was thrice elected to a seat in the Canadian Parliament but denied entry because of his revolutionary activities. Undergoing a profound religious experience that inaugurated his prophetic vision and project, his subsequent erratic behavior (reminiscent of “Kit” Smart’s) caused him to be institutionalized between March 1876 and January 1878. He eventually settled in Montana, where he became an American citizen. In 1885, however, the Métis enticed him across the border to lead them again in what became known as “the Northwest Rebellion”, which was summarily crushed, and Riel captured, tried, and hanged.

Riel’s editor writes concerning the Système philosophico-théologique:

There is good reason to think that this philosophico-theological synthesis was destined to be part of the Massinahican [Cree for ‘book’ or ‘bible’]. Regrettably, a number of pages are lost, and it is impossible to reconstruct with certainty the plan of this synthesis, which is why we have opted to present the few pages of this document thematically. The order of the texts that follows is intended to facilitate reading and does not pretend to reconstruct Riel’s intended order.

These pages were likely composed in Montana between 1881 and 1884. On many pages of the manuscript the paragraphs are numbered, but regrettably numbers 1 to 30 are lost; moreover, when there are several versions of the same paragraph, they do not have the same number; finally, there exist different paragraphs with the same number. There are therefore several series of numbers and one cannot trust that these numbers reconstruct with certainty the general order of the text.

In these pages, Riel uses above all the term ‘essence’ and more rarely the term ‘monad’ to designate the elements that constitute all reality. In God, the essences are all active; it is only in humankind that a mixture of active and passive essences is found. During his time in prison in 1885, Riel returned to his reflections on essences and monads…

The Massinahican, for all its truncated and fragmented brevity, is a startlingly syncretic, synthetic, and original work. Unlike Riel’s more identifiably prophetic, millenarian revision of (Roman Catholic) Christianity (as reminiscent of William Miller’s or Joseph Smith’s as that of the Ghost Dance religion), the Massinahican draws on Roman Catholicism and Leibniz’s Monadology, as well as coeval psychology, physics (electromagnetism), and, arguably, even Theosophy, sketching a broad, philosophical vision with affinities to Neoplatonism and Taoism, at least. Formally, arguably modelled in the first instance on Allan Kardec’s Le Livre des esprits (1857), the writing prefigures Wittgenstein’s argument-by-remark as much as it resembles the German Romantic Fragment (and, perhaps, even its ironies). As Tim Lilburn puts it in his own poetic explorations of Riel’s unfinished work: “Riel’s book Massinahican was an attempt to render old Rupert’s Land…into philosophy, interiority, and politics” and “We could be in a text by Proclus or Damascius”.

[A note on the translation. Riel’s notes were composed under various pressures, of inspiration and material conditions. They are, therefore, often orthographically and grammatically compressed to the point of obscurity, an obscurity further complicated by Riel’s own idiosyncratic inspiration and expression. We have often attempted to reproduce these ambiguities and difficulties in the English rather than present an artificially smooth and clear version of Riel’s thoughts.]

Addendum.

Tim Lilburn, from The House of Charlemagne (University of Regina Press, 2018)

SECOND FIGURE (Honoré Jaxon)

And, as you’ve said: “The prodigious concentration of the infinite essences in the loving man would have created for him the gift of subtle spirit. Cette concentration prodigeuse des essences infinies dans l’homme eût constitué pour lui don de le subtilité.” It’s all there in that single sentence. The human individual in the world’s birth canal.

Jaxon moves with great speed.

HONORÉ JAXON

Thus, swamped with the explosive throw, soaked with battling light, we, pneuma packets, breath bearded, harden (concress, vanish, anneal, zig but do not zag) into ever-fleet dots (he makes a gesture indicating the monadic shape), which Canadian grapeshot does not recognize and so misses.

Yes.

He shifts quickly fours steps, then stops.

Their instruments lack this precision.

I have heard you on this, this spirito-physics. What you scratched with care on pieces of elk hide and paper scraps deep in Montana, far in winters, 1881 to 1884. Many pages of this philosophical-théologique synthesis now lost, blown away in snow or raised in random fires. Your voice sways in me. Canadian bullets do not recognize me. We swim in a band below their apparatus’s range. Nor can the prime minister’s lit cigars cruise forward, drop as arrow-fall to press red circles on the skin of our arms when we are in this clenched, robed state of the active essences.

LOUIS RIEL

Snider Enfield rifles snuff and break twigs near.

A (post-secular) poem for Ash Wednesday

However much I was raised Catholic (and really enjoy Paolo Sorrentino’s gorgeous series The Young Pope and The New Pope), the Christian calendar orients me more mythopoetically than devotionally. Nor is the poem below as reverent (however elusively, allusively, and ironically) as Eliot’s canonical one, being more light-hearted and spontaneously post-secular. Nevertheless, I post below an Ash Wednesday poem from March End Prill (Book*hug, 2011).

Lift the flame

Luciferous hissing

blue out the lighter

Light the incenc

uous resins

crackle in the bowl

Father

Son &

Holy Ghost

Each cardinal direction

dawn morning sun

in branches

orientation

sinister

Southern Cross

Antepod

Abendland

Ol’ Rope-a

accidental occident

all that’s left’s

True North

“I believe”

Lichen yellows

Shady bark

A Timely Re-release: Peter Dale Scott reading from Minding the Darkness

Twenty years ago I got wind that Peter Dale Scott would be reading in the McGill University Library’s Rare Books Room. I had only recently discovered his work, in an excerpt from Minding the Darkness in Conjunctions, a poetry whose engagement with history and politics by means of an unabashedly citational poetics harmonized with my concerns and practice at the time, so I went.

When Scott solicited questions after his reading, I asked something like: “You have three books: the first [Coming to Jakarta] that begins by invoking three desks, at one Virgil’s Nekyia, an Inferno; then Listening to the Candle, a Purgatorio; now an old man’s Paradiso: all weaving historical, luminous details, personages modern and historical, autobiography, taking up the Tradition, all written in tercets: is there a Dantescan intertext?” to which he answered, “You, don’t go anywhere!”, an invitation to speak once all the other questions had been asked and answered. That was a fateful meeting, as Scott, the man and his work, have maintained an important place in my life and work, happily, since.

John Bertucci has now done us all the favour of uploading a video of Scott reading from that ultimate volume of his Seculum trilogy only a year after the one I attended. You can recapture an experience of Scott reading in the wake of the release of Minding the Darkness, here:

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment I first read in that brick of an anthology

I first read in that brick of an anthology