Archive for the ‘William Blake’ Tag

“Hell’s Printing House”—Budapest Suites (1994)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

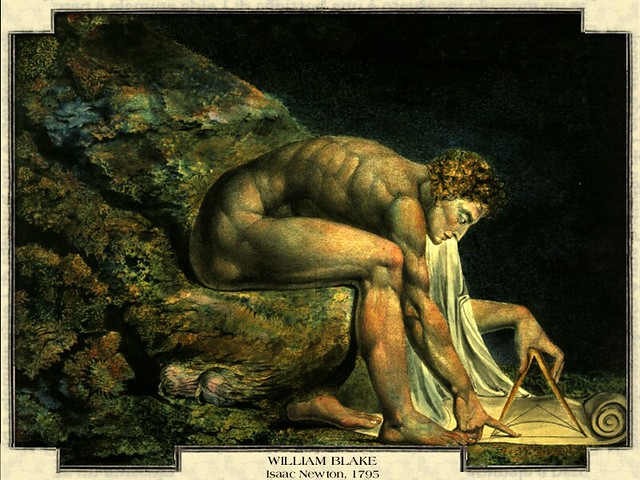

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Budapest Suites is the first published version of the titular poetic suite that later appeared, slightly revised, in my first, full-length trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems (1998). It, along with all books issued in the Pneuma Poetry Series, was designed and printed by my friend Richard Weintrager.

Contents

- “Apply what you know to what you feel that’s more than enough”

- “Mount Ság”

- “That he might…”

- “The chest-high white-haired Swiss woman asked…”

- “I went down to Bibliomanie”

- “Dan and I waltzed hopfrog…”

- “You don’t just follow an impulse do you?”

Budapest Suites collects poems written during and after a 1991 trip to Europe (my first!), whose highpoint was a visit to Budapest and Celldömölk, the hometown of scholar poet friend Kemenes Géfin László, there to be honoured for his literary work and to launch his avant garde epic work Fehérlófia (the son of the white horse). On that occasion, we visited the extinct volcano on the outskirts of town Mount Ság (Sághegy) where Géfin had hidden out during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 before escaping over the border to Austria. Géfin was struck by the lushness of the locale, so much he was moved to remark, “There is a god here!”, the opening line of the second suite.

In Budapest, I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of some American ex-pats, among them, writer Dan Philip Brack (DPB), “Dan” in the opening line of the penultimate suite. Let’s attribute the epigraphs of the first and last suites to him. The fourth suite commemorates a visit to the National Museum. The third suite, as well, was written in situ. The fourth suite was composed after returning to Montreal; its being slightly confusing might be attributable to its being “a mystical poem,” as Hungarian poet Tibor Zalán called it.

The poem recorded below is the third suite. Darius Snieckus, author of the inaugural chapbook in the Pneuma Poetry Series, The Brueghel Desk, was so impressed when he read it, he insisted I not “change a thing!”. His anxieties were not unfounded, as up to and into the writing of the Suites, I had been an obsessive reviser: I still have the notebook with the seventeen (at least) versions of “Mount Ság” worked over that one afternoon, including the Hungarian translation by Zalán and András Sándor, which was read to Géfin on site in honour of the visit.

It was in revising the fourth suite that the most recent, nth version turned out to be identical to the very first. It was then I learned the truth of William Blake’s dictum “First thought best in Art…” From that revelation on, my compositional practice was to write, then carefully study what had been written to understand its spontaneous rightness before cautiously making slight alterations, only in order to bring out the energy of that original impulse all the better. It was Joachim Utz, one my most careful German readers, who noted that the Budapest Suites marked a “breakthrough” in my poetry.

Next month, Gloze (1995)…

Comments (2)

Comments (2)