Archive for the ‘The Brouillon’ Category

D. M. Bradford’s latest: Bottom Rail on Top

Former student and present poet friend announces the imminent publication of his second trade edition, Bottom Rail on Top, “a kind of archives-powered unmooring of the linear progress story [that] fragments and recomposes American histories of antebellum Black life and emancipation, and stages the action in tandem with the matter of [the poet’s] own life.

You can hear the author say a few words on his new book and pre-order it by clicking on its cover:

Absolutely modern Romanticism

Welcome news from Jerome Rothenberg concerning a new initiative by Jeffrey C. Robinson, with whom he edited an essential assemblage Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: Romantic and Postromantic poetry.

Announced is a putative collection of “75 or so statements, terms, and jargon from the ‘Romantic mother-lode’ (Anne Waldman) with the hope that together, with accompanying commentary, they will accumulate irrefutably a major well-spring for modern and contemporary innovative poetry,” a collection that will prompt a “recognition of [romantic poetics] as a loose system of outlandish thought for the renovation of poetry in the service of a renovation of society.” Robinson highlights a handful of salient concerns (in his words): a new view of the world, sub specie aeternitatis; the not unrelated symbolic implications of Jacob’s Dream; the Fragment as Coherence over Unity and the Future; and a stance Against “palpable design”.

Romanticism, as a sensibility, but always too-much anchored to a concept of its being an historical period, has been resurgent, at least, since the reaction to the strictures of (at least, anglophone) literary Modernism (e.g., the criticism of T. E. Hulme, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) and the (ideological) aesthetic of the New Criticism. The poetics at work in the poetry of Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg and in the criticism of Harold Bloom, Geoffrey Hartman, and Paul de Man are well-known examples of this countermovement. However, first, with the scholary innovation of “constellation studies” and the resultant, rigorous reappraisal of Jena Romanticism and German Idealism (here, the names Dieter Henrich, Manfred Frank, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Andrew Bowie are exemplary) through the 1970s and 1990s served (at least among those paying attention) to utterly reorient the place and value of the thinking called “Theory” and the poetics and compositional practice that Theory influenced. Into this context, though with their own perspective on the matter and what’s at stake, step Rothenberg and Robinson with the above-mentioned assemblage (2009), the accompanying volume of poetics Active Romanticism (eds. Julie Carr and Jeffrey C. Robinson, 2015), and Robinson’s just announced project.

However much my own thoughts (and practice) are more or less in harmony with Robinson’s, there are points both of disagreement and concurrence. Coming of intellectual age studying Existentialism and Phenomenology (which, like Sartre, has led to an engagement with Historical Materialism) I’m leery of the invocation of the Spinozistic idea of viewing the world (and human life (and history)) sub specie aeternitatis (though, admittedly, Robinson does spin this notion in his own way). My aesthetic is very much, as I say, “ontological”, attending to what is given as the primary material, a nonjudgemental sensibility as phenomenological, Objectivist, “mindful”, or—as our romantic forbears (and descendants) put it, “prophetic” or “vatic”, an aesthetic that might well be said to be, in Robinson’s words, “forgiving.” In as much as such a stance is variously “estranging”, a literary value articulated by Novalis and Coleridge well in advance of Shklovsky, I am, again, in agreement. More philosophically (if not fundamentally), the view Robinson espouses here is in line with various posthumanist philosophical movements, such as Object Oriented Ontology (despite its antiKantian stance) and Timothy Morton’s not-unrelated Dark Ecology, the renewed interest in psychedelics, and other attempts to re-enchant the world, such as those of scholars Jeffrey Kripal, Jason Ãnanda Josephson Storm, and Marshall Sahlins, currents that pique my curiosity but no less my skepticism.

Robinson’s invocation of the fragment is welcome; my own poetics orbits the metonymical, which is essentially fragmental, in the Romantic sense. I find the futurity of the fragment demands more brow-furrowing; the optimism of writing for the future must, as, for example, much of the early writing of the Beat Generation did under the shadow of nuclear annihilation, be tempered by the very real possibility of cultural-historical foreclosure, the anxiety that has moved many young people from reproducing in the face of the threats of climate change…

What I find of most promise in Robinson’s proposals is his invocation of a poetics that eschews a “palpable design” (“We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us,” in Keats’ words). This approval might seem jarring in light of my invocation of the climate crisis and my admitted Historical Materialist sympathies, but anyone who has read, for example, Adorno’s essay on the drama of Sartre and Brecht “Commitment” will have a better idea of a writing without “palpable design.” Robinson invokes Vicente Huidbro, the Chilean poet of Altazor, “who locates palpable design as an intrusion of the ‘horribly official stamp of approval of a prior judgment (perhaps of long standing) at the moment of production’.” As Robinson glosses Huidbro:

Palpable design, while it may have been internalized, comes from without, from the social and cultural spheres, from “custom,” from the panopticon, from a voracious market economy with its association of any product, including a poem, with its acquisition, and from gender, race, and class inequities; it appears in poetry as received forms and received modes of speech that produces the familiar and consoling.

Here, Robinson’s writing of the fragment as a “pro-ject” invokes vital aspects of Olson’s Projective Verse as much as Nicanor Parra’s “anti-poetry” and the creative spirit and attendant strange novelty (creation) that runs from Dante, Cervantes, and Shakespeare (the Holy Trinity of the Jena Romantics) down to today. What is demanded by unprecendented times is an unprecendented poetry. Indeed, we live on a planet never inhabited by Homo Sapiens. What more radical call to make it new could be sounded?

Willow Loveday Little on James Dunnigan’s Windchime Concerto

Like, wow.

Very happy to share here a brief but no less impactful review/essay by one of Montreal’s—nay, English Canada’s—most exciting young poets on another no less exciting young poet.

You can snag a copy of Little’s first trade edition, (Vice) Viscera, here. Read her review essay here.

(Did I mention the folks at Yolk are doing great things?)

Five new poems in The /Temz/ Review #21

The /Temz/ Review has kindly published five recent poem of mine, along with poems, stories, and reviews by many others. You can read it all, here.

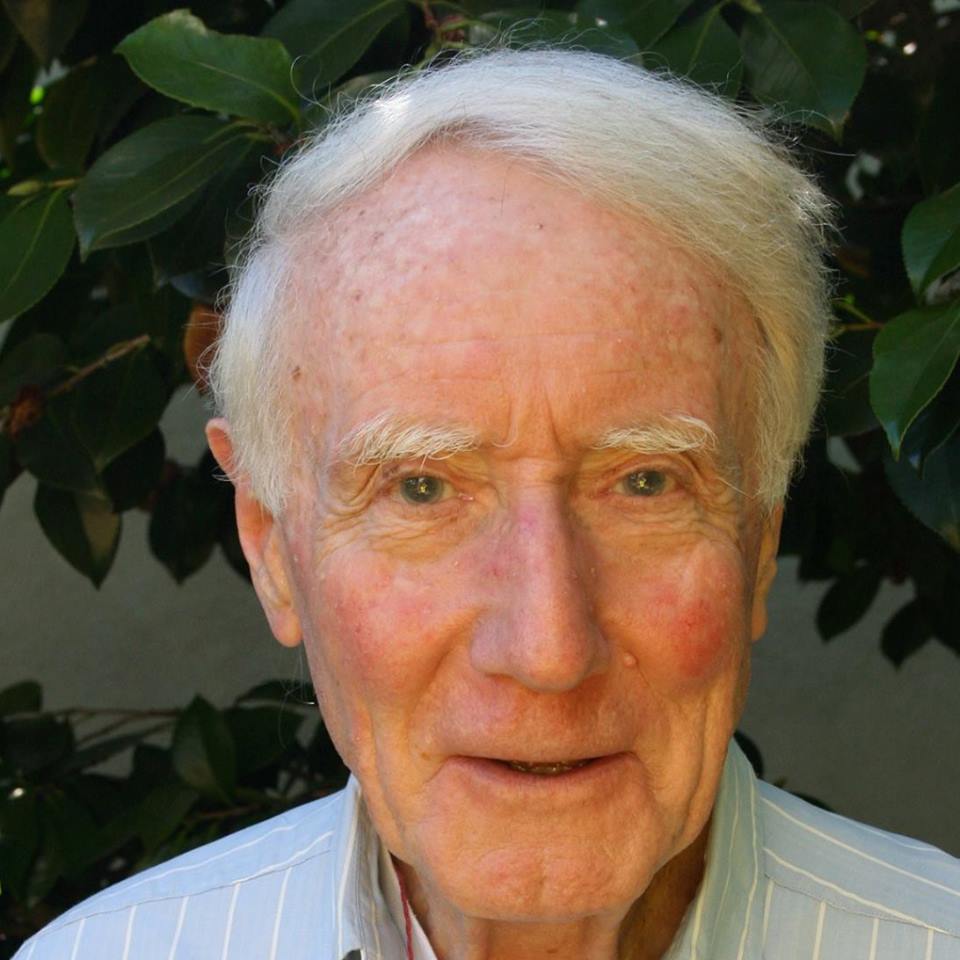

Help Peter Dale Scott with publishing two new, important books

Freeman Ng has organized a Fundraiser to help cover costs in producing two new books by Peter Dale Scott.

Peter Dale Scott is a poet, political researcher and former Canadian diplomat whose books include The Road to 9/11, The American Deep State, and Seculum, a trilogy of book-length poems — Coming To Jakarta, Listening To The Candle, and Minding The Darkness — that poet and critic John Peck called “one of the essential long poems of the past half century.”

At 93 years of age, Scott is finalizing two new books, to be published through Rowman & Littlefield, that he considers to be the most important he’s yet written. However, he’s facing licensing fees and indexing costs he’s unable to meet on his limited pension. (On top of unexpected medical bills for three recent hospitalizations due to COVID and pneumonia.)

Please help him meet these costs.

The two books are:

- Ecstatic Pessimist: Czeslaw Milosz, Poet of Catastrophe and Hope, which would be the first recent general analysis of the Nobel Prize-winning Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz intended for English readers, and which Robert Hass, a former U.S. Poet Laureate and Milosz’s principle translator, called “a brilliant and illuminating book on the complex and essential poet.”

- Enmindment — A History: A Post-Secular Poem in Prose, a book on the role of poetry in cultural evolution.

You can access the GoFundMe site, here.

You can read an appreciation of Scott’s poetry, the first post on this website, here.

Two poems newly online and in print!

With a deep bow of gratitude to special editor Karl E. Jirgens, I’m glad to share two poems in the most recent number of the Hamilton Arts and Letters Magazine. Among the many auspicious names, I would direct interested parties to the unnervingly talented contributions of James Dunnigan and Willow Loveday Little.

This way to Sàghegy…

One of the editors here at Poeta Doctus is synchronicity. And, after all, what poetic sensibility isn’t tuned to the rime of meaningful coincidence?

To wit: a friend recently shared a photo from a small town near where he presently lives in Hungary, Celldömölk. Now, it so happens I visited Celldömölk in 1991 to honour the publication of a friend’s avant garde epic work Fehérlófia (the son of the white horse). In the upper right hand corner of the picture, you can see directions to the nearby vulkán, the extinct volcano Mount Ság (Sághegy).

Among other claims to fame, Sághegy is where the epic’s author, Kemenes Géfin László, hid out after participating in the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, before he was able to flee to Austria and eventually to Montreal, Canada, where I was fortunate enough to make his acquaintance. Returning to his home town and the flanks of Sághegy thirty-five years later, Géfin was struck by the lushness of the locale, so much he was moved to remark, “There is a god here!”

To honour the occasion, I sat and furiously composed some forty different iterations (I still have the small, black notebook) of what eventually became the second Budapest Suite. To honour this most recent synchronicity I reproduce Budapest Suites II, below, and share a reading of the poem.

Budapest Suites II

for Laszlo Géfin

“There is a god here!”

In wild strawberry entangling thistles,

In maple saplings, a shroud on loam,

In chestnut and cherry blossoms over tree-line,

In goldenrod and grass, every green stalk, bowed with seed.

And there is a god who

Quarries slate for imperial highways,

Mines iron-ore out of greed,

Who would have Mount Ság again

Ash and rock.

And there is a god

In the seared, scarred, spent, still,

For lichen, poppies and song

Here rise from the bared

And broken rock to the air!

A short interview with Griffin-nominee, David Bradford

Griffin Trustee Ian Williams interviews (my) ex-student and poet-friend David Bradford about his Griffin-nominated first book Dream of No One but Myself. The conversation ranges over the book’s matter, some of its compositional gestures, and the title, and includes a short reading at the end.

Here’s looking ahead to the announcement of this year’s winners on Wednesday, 15 June!

Absolutely Modern Compositional Praxis (a title sure to make this post go viral!)

The indefatigable Kent Johnson continues his running battle with any and all complacencies, real or apparent, in (at least) the American anglophone poetry community. As is often the case, he’s been carrying on a running battle with various L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets, recently with Bruce Andrews. Interested parties can visit Johnson’s FB page where these threads unwind, but I share here a latest back and forth to pin the point I want to make on:

MORE EXCHANGE ON LANGUAGE WRITING, WITH BRUCE ANDREWS (continuing from yesterday)

Bruce Andrews wrote:

>No grudges about a peer [Eliot Weinberger] who I never found to be “brilliant” & who made what I considered many uninformed “categorical polemics” about a range of experimental (&, yes, intransigent) writing; it was a comment about the thread of responses you’ve mobilized here (& tend, for whatever personal reasons, to mobilize/trigger) into sweeping disavowals of a very large range of poetry that I’ve cared very deeply about — so are we talking about Peter Seaton or Hannah Weiner or Tina Darragh or P. Inman or Diane Ward or Michael Gottlieb or Alan Davies or Steve Benson or Abigail Child or Lynne Dreyer or WHO; this visceral attack/dismissal mode [not duplicated, by my reckoning, in my own published responses to poets I don’t get enthusiastic about] is what I find to be … SAD ~

*

I replied:

Bruce, sorry, but you’ve got it wrong. I’m on record as having a conflicted stance in regard the Language formation.

Sure, I’ve had my strong critiques (that’s part of poetry, right?). And I’ve engaged in satire, as well (that used to be part of poetry, too, no?). But I’ve never turned that into a sweeping dismissal of the tendency. To the contrary: I’ve written more than anyone, so far as I can see, about how you folks quickly capitulated on your original, stated ideals–one of the most rapid “avant-garde” recuperations ever, and one that has had far-reaching consequences in the sociology of U.S. poetry. That’s a good kind of critique, even a comradely one…

All in all, compared to some of the outright character assassination directed against me by a few of the top reps of the Language group and its junior satellites, I’ve been pretty damn reasonable.

The moderately-attentive reader will understand, I wager, that the dispute is, vaguely, critical, invoking as it does “polemics,” “disavowals,” “attack,” and “dismissal”. Johnson has, in recent days, been advocating for a poetry criticism that doesn’t shirk from being “negative”, whether witty or downright mean (interested parties can scroll back on Johnson’s FB page to see numerous examples…). Those of us in (anglophone) Canada who suffered the Reign of Terror of the Axis of Cavil at Books in Canada and the “negative reviewing” it practiced and advocated will likely sigh, roll their eyes, and thank their lucky stars those days are over. A generation later, and it’s hard to discern just what beneficial effect all the bile and venom spit those days might be said to have had on our poetry….

Johnson’s critical polemic isn’t merely aesthetic, however. Many poets associated with L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, especially Andrews, Charles Bernstein, Steve McCaffery, and Ron Silliman (among others) adopted an overt, specific, political stance, which Johnson never tires of taking to task (“how you folks quickly capitulated on your original, stated ideals—one of the most rapid “avant-garde” recuperations ever”). One can, however, prise the poetic from the political, here; Johnson’s critique is aimed not so much at the poet-as-poet but the poet-as-citizen, a not unimportant distinction. Not that poetry is not inextricably social (however much the aesthetic arguably is not reducible to the ideological), but Johnson’s dogged persecution of the poets’ hypocrisy diverts attention from strictly poetic concerns, including the question of poetry’s being political.

More urgently for the practicing poet and interested reader (critic or otherwise) is the aesthetic-compositional significance and legacy of the poem or poetry in question. In the case of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E (if one can even grasp the “school” as a unified totality, which Andrews calls into question supra), what’s at stake for the poetry is the success and failure (it’s always both) of its intended effect, the articulation of the linguistic medium to achieve that end, and the uncontrollable subsequent reception of the work, aesthetic and otherwise. Of even greater importance is what resources for compositional praxis does the work have for today (a day that is always new).

This question looks both backward and forward. The poetics of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E is no longer novel, (however much every reading always differs from the previous), so any estimation of its remaining compositional resources needs contrast the horizon or social matrix of its emergence from that or those in place today, however ephemeral. Moreover, any deployment of its compositional potential that puts it into play today sets the resulting text free into the future; the poem will be received in unpredictable ways. In this sense, “all poetry is experimental” (if that adjective, first used in English by Wordsworth and Whitman, can be said to still be of much use). It should be pointed out, further, the potential of any given compositional technique is never given once and for all; its pertinence and promise is always local.

The ironic (or dialectical…) consequence of this insight is that “the absolutely modern” in terms of what compositional examples might be drawn on is in harmony with Blake’s dictum that “The Authors are in Eternity,” i.e., from the point of view of the pragmatics of composition the poetic inheritance is free of the conditions that determined the moment of its composition and immediate reception. At the same time, however, no practice can anymore claim to be sanctioned by Tradition: every inherited technique, every articulation of the linguistic medium is subject to interrogation: how does it work now? Such an absolutely modern sensibility works with/in a temporality wherein “all ages are contemporaneous” but the moment of composition and the immediately foreseeable moments to follow (insofar as they are foreseeable) is grasped by its relative singularity.

Much, much more, of course, could (and probably should) be said. Moreover, the cognoscenti will detect the position I adopt here doesn’t move much past the notions of poetic development or evolution developed by the Russian Formalists a century back and even draws on Matthew Arnold’s criticism in some respects. Nevertheless, the point I want to make here is a simple one, if all too often forgotten: if you’re going to kick the poetic ball, ya gotta keep your eye on it.

David Bradford’s Dream of No One but Myself nominated for a Griffin!

This year’s Canadian nominees for the Griffin Poetry Prize include friend and ex-student David Bradford‘s first book Dream of No One but Myself.

Bradford’s is one of a number I’ve been trying to get around to writing about here at Poeta Doctus. Now, I guess, there’s even more reason. Do yourself a favour, click on the title above, and get yourself a copy, so you can better appreciate that review/notice when it finally gets written and posted, or, better, support a poet whose words call out for close attention.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment