Archive for the ‘Canadian poetry’ Tag

An Old Man’s Eagle Mind: on Peter Dale Scott’s Dreamcraft

The publication of Peter Dale Scott‘s latest volume of poetry is bookended by last year’s appearance of his study of Czeslaw Milosz, Ecstatic Pessimist, and this year’s release of Reading the Dream: A Post-Secular History of Enmindment, quite the trifecta for a man who turned ninety-five in January of this year (2024).

The poems collected in Dreamcraft, on might say, have vista. This latest volume’s being published in the poet’s ninety-sixth year, it comes as no surprise to find poems on old age. “Eros at Ninety” is both humbly, humorously self-deprecating and wise. “A Ninety-Year-Old Rereads the Vita Nuova” and “After Sixty-Four Years” ruminate over the changing experience of art, here, that of Dante and Grieg, within a lifetime’s perspective. The longer one lives, the more acquaintances one loses to death: elegies for lost friends—Robert Silvers and Scott’s lifelong friend Daniel Ellsberg, among them—take up nearly a third of the book. Four poems are addressed to Scott’s friend, Leonard Cohen, the book’s title track, “Dreamcraft,” the explicit elegy “For Leonard Cohen (1934-2016),” “Commissar and Yogi,” and a poetic back-and-forth the two shared just before Cohen’s death, “Leonard and Peter” (included, as well, in the last collection of Cohen’s work, The Flame). The volume’s perspective, from within “the long curve of life” (words from the book’s first poem, “Presence”) is evident in the poems that embed the poet in larger processes, whether “the bicameral brain that makes // obsfucation of mere fact / so much more beautiful” (“The Condition of Water”), our genetic character (“Dreaming My DNA”), the Earth itself (“Deep Movement”), “cosmic space / …knowable / by those specks of light // at great distance from each other,” or History’s ethogeny, which Scott glosses as “cultural evolution” (“Moreness”). Loss and the long view bring the poet’s closest relations into focus in more intimate poems, those for his daughter, Cassie (“To My Daughter in Winnipeg” and “Missing Cassie”) and wife, Ronna Kabatznick (“Enlightenment” and “Red Rose”).

Last year’s publication of Ecstatic Pessimist: Czeslaw Milosz, Poet of Catastrophe and Hope reveals Milosz as a kind of éminence grise in Dreamcraft (and, indeed, throughout Scott’s poetry). Though their friendship at the University of California, Berkely, was short-lived (roughly from 1961-1967), Milosz’s notions of the function of poetry and the poet, as one whose “poetic act both anticipates [an emancipated] future and speeds its coming,” are determinative: anyone at all familiar with Scott’s poetry and prose will hear the echo of Milsoz’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “In a room where people unanimously maintain a conspiracy of silence, one word of truth sounds like a pistol shot.” Scott’s lifelong relationship to Milosz’s poetry and thought, if not with the man, finds expression in the five-part sequence “To Czeslaw Milosz,” wherein Scott reflects on that relationship, one Polish word or one poem or idea at a time. This sequence is balanced, as it were, by “The Forest of Wishing,” originally published in 1965, which addresses (among other things) Milosz’s reaction to the American Counterculture of the 1960s in an earlier style of Scott’s, remarkable for a more elusive density of suggestion than is found in his poetry from Coming to Jakarta (1988) to the present volume.

Scott’s mature style might be said to take its cue from Milosz’s admonition (also from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech) that the poet need “liberate [themselves] from borrowed styles in search for reality.” The result, in Scott’s case, is sure to irritate those readers who need their poetry to “tell it slant” (whether that spring from a post-Eliotean prejudice for “metaphor” or a post-Language demand that the linguistic medium be estranged, if the aesthetic inclination is even so self-aware). A case in point might be the poem “Pig”:

Aside from the poem’s being a recognizably generic “lyric” (a first-person anecdote climaxing in an epiphany), I can well imagine readers with a taste for the mimetic virtues of, say, Seamus Heaney, Eric Ormsby, or (more recently) Kayla Czaga, or the verbal deftness of Michael Ondaatje at his best, dissatisfied with the description of the pig’s butchering (in the second, third, and fourth tercets), desiring in place of, for example, the words ‘slaughtered’, ‘cutting’, and ‘squealing’ at least a more sensuously robust diction if not a vividly inventive image to present rather than refer to the action. Such readers would be even more scandalized by the poem “Mythogenesis” with its opening “The OED defines / both mythopoeia and mythogenesis / as the same: the creation of myths,” lines which set the tone for the explicatory prosaicness of the poem that follows (a prosaicness, however, that slyly reproduces, line for line, the original email sent to the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary). I, too, have struggled for my own reasons with this tendency in Scott’s style over the years, and, were this notice a “review,” I’d be obliged to indulge in the workshop nit-pickery that would find fault with (“criticize”) a certain word choice here, a syntax that might be made more mimetic there, or even the collection’s title, but such an approach too often merely brings into view the reviewer’s prejudices or limitations (let alone the hatchet they might have to grind) than serving to illuminate the work under consideration (a problematic addressed, in fact, by the book’s penultimate poem “A Quinkling Manifesto”). Scott, himself, has responded to critics who find his poetry too prosaic, reminding them the same accusation was levelled at the prosody of Williams Carlos Williams a century ago. One could point to that other compositional sensibility (with which Williams was briefly associated) present in the “Objectivist” poets (notable for their engagement), among them, Lorine Niedecker, Carl Rakosi, or Charles Reznikoff. But more to the point, it is precisely this clinamen of Scott’s style, the way it swerves from any such obvious borrowings or influence, that is an index of that essential drive in his entire oeuvre, a “search for reality,” the telos of his work that is the principle measure of its success or failure, if a critical judgement is indeed called for.

As I’ve observed, the poems in this latest (if not last) volume take the perspective of “an old man’s eagle mind” (as Yeats called it), wherein “the long curve of life” becomes visible, the horizon for whatever else might come into view. This perspective is, perhaps, no more evident than in the book’s final, thought-provoking poem with its explicitly ethogenic theme, “Esprit de l’Escalier“:

The poem, in post-secular fashion, has as its epigraph a verse from the Book of Zechariah (4:6) (Scott the first to my knowledge to articulate a post-secular sensibility, in advance of Habermas’ developing the concept in its present form in 2008), a verse with tonal implications for what follows. We are admonished to “not just talk about politics // which let’s face it / we can do nothing about” (at least those of “us here / at this Chanukah table”) but “about culture // preparing people’s minds / for tomorrow’s revolution” (words which, again, echo Milosz’s “The poetic act both anticipates the future and speeds its coming”). Curiously, the poem speaks of a “black windshield” (likely the image that, in part, inspires the book’s cover art) “smeared… // with the grime of facts,” a brow-furrowing sentiment to flow from the pen of so assiduous a researcher, whose work, prose and poetry, has laboured to uncover that “conspiracy of silence” and scatter it with a resounding “word of truth.” (That is, perplexing as long as we remain insensitive to the potential tonal complexity of ‘facts’ and the even more important and profound distinction to be made between “facts” and truth…). This grime is to be cleaned “with hope,” a hope that waits for “the great poet // on whose shoulder / that eagle flying / above and ahead of us // in the darkness / will come down briefly to rest.” These lines are richly suggestive. On the one hand, they mark Scott, I think, as one of those increasingly rare poets who demand poetry play an orienting if not guiding role in culture and society. On the other, that “eagle flying / above and ahead of us” is at first elusive as allusive. Is it a mere—if complex—metonymy, invoking the eagle’s powers of sight? Does it allude to the eagle formed by the just souls in the heaven of Jupiter in Paradiso XIX? Is it a symbol of God, via the bird often associated with Zeus (‘Z-eus’, ‘d-eus’ (which, regrettably, only rime with ‘th-eo’…))? More tentatively, it brings to this mind, anyway, the idea of the kommende Gott, the “coming god” in Hölderlin’s “Bread and Wine” (however much that god is, in fact, Dionysius…), perhaps that god who is the only one “who can save us” in Heidegger’s late, portentous phrase. This interpretive question is resolved, however, by turning to Reading the Dream, where we discover Scott’s eagle alludes to the spirit of Rousseau in Hölderlin’s ode to the French thinker, that “flies as the eagles do / Ahead of thunder-storms, preceding / Gods, his own gods, to announce their coming” (“wie Adler den / Gewittern, weissagend seinen / Kommenden Göttern voraus“). The rich figurative resonance of these lines that demands such learned, interpretive labour marks them, too, as belonging to a past, if not passed, poetic, one rarely practiced today, if at all.

For many, I think, Scott’s vatic stance in this poem (however domesticated in its opening scene) and the faith in poetry it expresses will place him beyond a certain pale. The present, at least North American, mood is more skeptical. Those with some historical sense will too easily remember those poets who aspired to influence, cultural, social, and political, and went “wrong, / thinking of rightness.” Auden’s words, “poetry makes nothing happen,” still express a common sentiment, and, for those who do engage the question of the relation of poetry and politics seriously, it remains an open-ended, complexly recalcitrant problem. In his defense, Scott, in Ecstatic Pessimist, invokes Virgil, Dante, Blake, Shelley, and Eliot (6). More forcefully, Scott’s study of Milosz is a sustained argument for the potential social force of poetry, exemplified by his subject, notably “his contributions in the 1950s and 1960s to what became the intellectual culture of Solidarność” (5). What is striking is how this last poem in Dreamcraft departs from Scott’s characteristic poetry-of-truths that ring out like “a pistol shot.” It might be argued that its prophetic vision, of that mysterious justice-to-come and its poet, draws on poetry’s power to posit the counterfactual (how matters could or should be, to paraphrase Aristotle), to imagine a non-place (u-topos), a place that is not because it is only yet-to-be, and only potentially so. In contrast to the probing of uncomfortable truths (facts) characteristic of so much of Scott’s poetry, the fictionality of the poem’s vision (its being (only) imagined) invites, demands, a suspension of disbelief (the condition of imagining what is not as if it were), evoking our Negative Capability, that ability to live “in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” By its very unreality, then, the poem evokes that resolve that poetry—and social action—require….

That Scott’s oeuvre in this way, from his Seculum trilogy to Dreamcraft, demands the engaged reader to consider and wrestle with the art of poetry, poetry and politics, investigative fact and visionary fiction is evidence of its sophisticated achievement. Such reflection, it has long seemed to me, is the condition for any understanding of poetry, worthy of the name, an understanding that needs precede any critical appraisal. This resistance to a ready assimilation to existing literary-aesthetic canons—despite the surface, apparently-prosaic transparency of the poetry—testifies to Scott’s poetry’s being poetry, making, creating works possessed of a novel uncanniness that adds something new, not merely accomplished, to the world of letters, if not the world-at-large.

(If so moved, you can purchase a copy of Dreamcraft by clicking on the book’s cover, above.)

Hell’s Printing House: Luffere & Oþere: Amoretti from Marchend Prill (2003)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

The first five chapbooks I’d bound were made to collect and “publish” work otherwise unpublished in periodical or book form. Luffere & Oþere marked a departure, as it was the first chapbook that collated the poems I was to perform at a reading. At the time, Ilona Martonfi organized (among many other events) an annual Valentine’s Day reading, “Lovers and Others,” and kindly invited me to read. I don’t remember exactly what reasons I gave myself at the time, but it seemed somehow appropriate to have the poems I would read ready in print-form for interested parties, a good opportunity to issue a new chapbook, a practice I was to maintain for many years. Luffere & Oþere are the oldest forms of the words ‘lovers’ and ‘others’ in English.

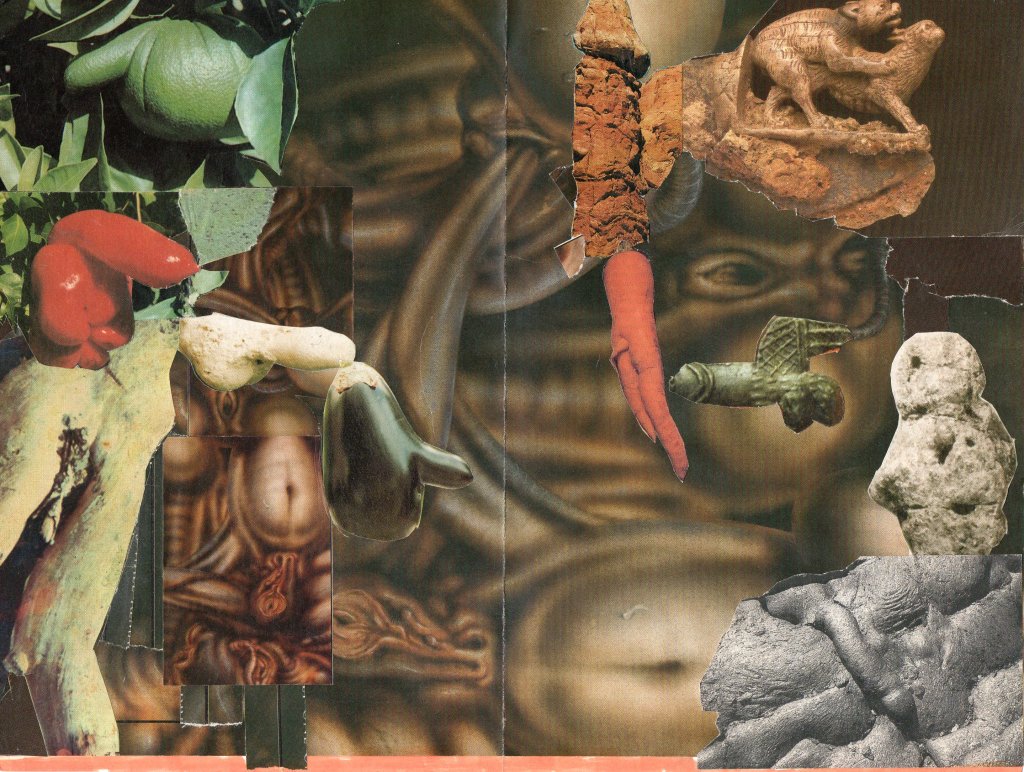

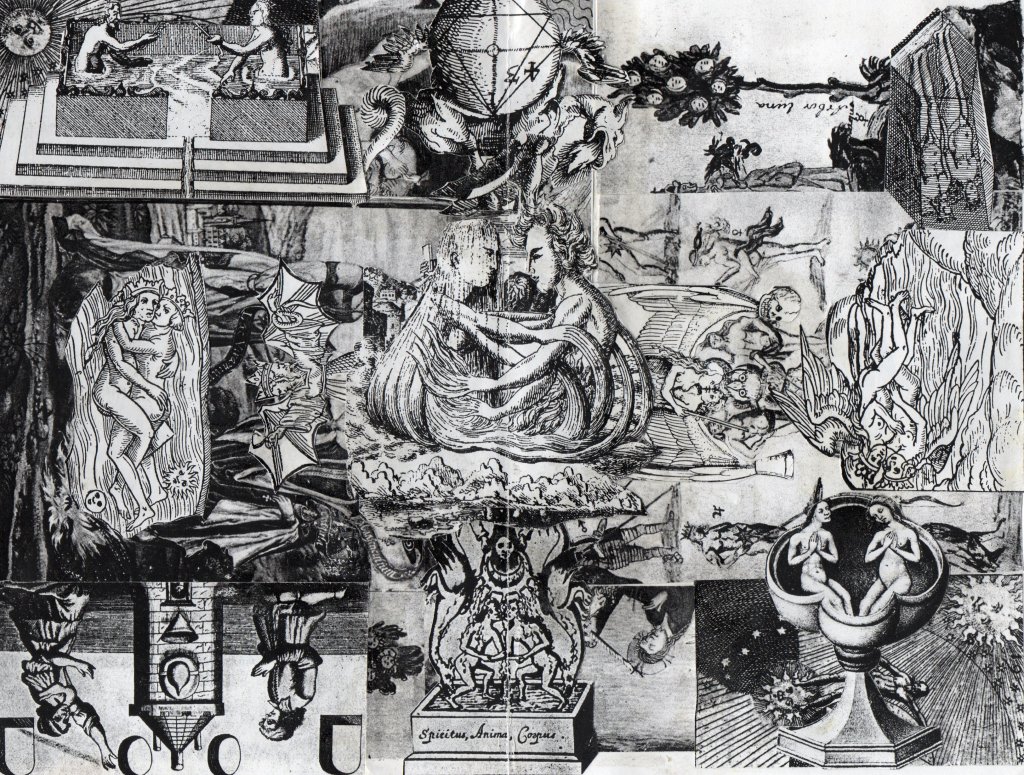

Not only was this chapbook the first made for a reading, but it is also the first with original artwork (in this case, two collages) for the flyleaf, outer and inner:

However much amor is one of the great poetic themes, it’s not one I have often dared (except for one poem, known only to my closest friends). However, at the time, I had written a poetic sequence, an extension of the concerns motivating X Ore Assays and Seventh Column, that was to be published years later in 2011 by Book*hug, March End Prill. This sequence, compositionally, adhered to a resolutely Surrealist poetic (“the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns”), informed as much by Breton as by ethnopoetics:

Songs are thoughts, sung out with the breath when people are moved by great forces & ordinary speech no longer suffices. Man is moved just like the ice floe sailing here and there in the current. His thoughts are driven by a flowing force when he feels joy, when he feels fear, when he feels sorry. Thoughts can wash over him like a flood, making his breath come gasps & his heart throb. Something like an abatement in the weather will keep him thawed up. And then it will happen that we, who always think we are small, will feel smaller still. And we will fear to use words. But it will happen that the words we need will come of themselves. When the words we want to use shoot up of themselves—we get a new song.—Orpingalik

At any rate, I combed through March End Prill and abstracted a sample of, if not all, the poems defensibly “erotic.” The titles are their first lines or the first words thereof:

Contents

- falling asleep

- she was coming for supper

- durée

- dear Wife

- we must really be out of touch

- Can’t wait for you

- mornings spooned

- When I get the chance

- my old friend dumped his

- Godammit! Love’s

- Bedrock

Here’s a new recording of these poems, for those who missed the reading!

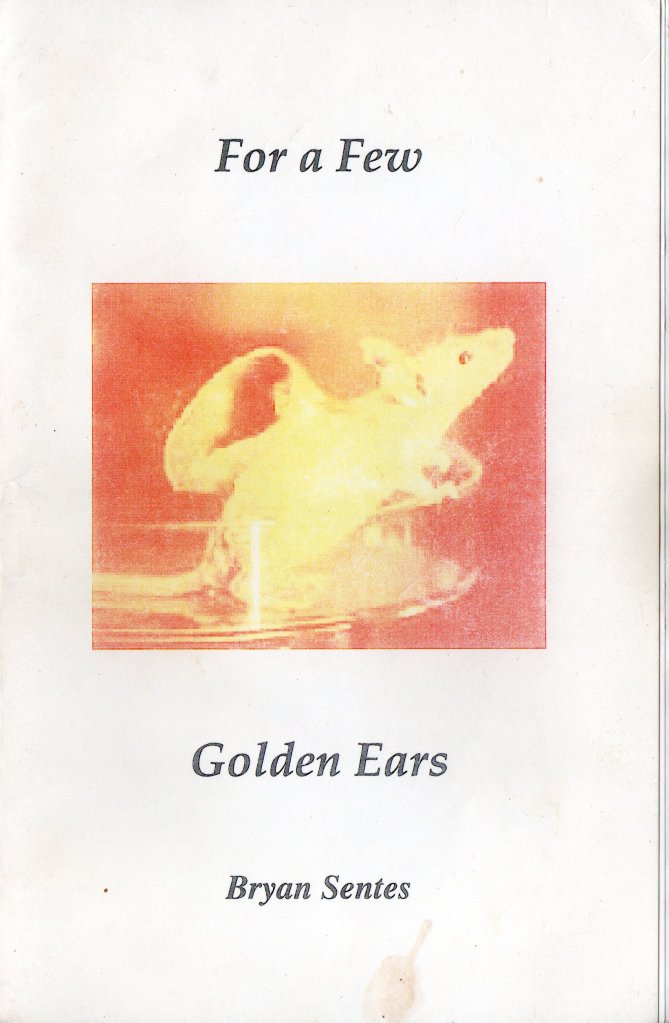

Next month: For a Few Golden Ears (2004).

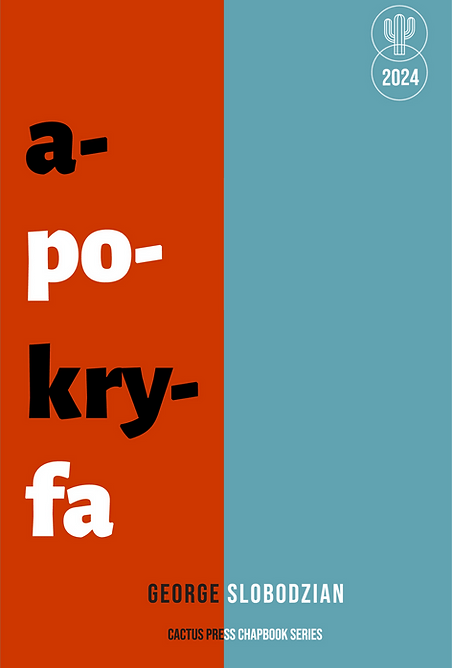

On George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa

Culture must be—as the word itself might suggest—cultured, seeded and carefully tended. Such care takes many forms in Canada, from ever-diminishing (if however appreciated) government funding, to the selfless, meagrely-rewarded efforts of those who—in the case of our literary culture—publish small magazines and books of poetry, to more grassroots efforts.

In recent years, in Montreal, Devon Gallant and collaborators have cultured an urban poetic garden, organizing the Accent Reading Series, which combines an open-mic (as polylingual as the city) and a spotlight on one or two featured readers, and which has, accordingly, gathered a small, poetic community. One of the fruits of this endeavour is Cactus Press, which, to date, has issued over thirty chapbooks and the first trade edition of the unnervingly-talented Willow Loveday Little, (Vice) Viscera (2022).

One of the newest of these chapbooks is George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa, his second with Cactus Press. Apokryfa gathers eighteen poems, old and new, organizing them in three sections, “In the Garden,” “Et Homo Factum Est,” and “Tale.” The first reflects on childhood and youth, the second works up and on, more-or-less, Catholic mythology, while the last reworks fairy tales. However much at first glance these sections might suggest a progression from autobiographical truth to overt fiction, a more canny, poetic sensibility is at play that subverts such too-easy, hard-and-fast distinctions.

But this sophisticated sensibility is only one aspect of these eighteen poems, which, perhaps more importantly, reveal a poet at the top of his game. While, from the “Tale” section, “Other Dwarves” and “Deliverance” (a riff on “Rapunzel”), might seem relatively light, they are not without their wit (in the case of the former) or rich suggestiveness (in the case of the latter). Most of the poems are, however, so to say, more thematically substantive. “Radisson Slough,” recounting how the boy speaker “Out hunting with [his] father / and brothers, …was the dog,” concerns as much a moment in one’s lifelong loss-of-innocence as much as, perhaps, weightier epistemological matters when “in search of the warm reward / of a grain plump duck,” the boy finds “instead the corpse // of an abandoned crane / half-submerged and corrupt, / its great wings still engaged / in a sort of flight until” he touches it, and it sinks. “The Annunciation” in the chapbook’s second section, “Et Homo Factum Est” grimly recasts the Archangel Gabriel as the agent of some unnamed totalitarian regime with an uncannily ironic gift of prophecy who foretells the life of the expected son, a malcontent (and who wouldn’t be under such a system?) who leads “an entirely unremarkable childhood,” in the end only to “be taken / into the appropriate custody” to finally succumb “to his diseases.” And, in the book’s final section, that persistent question if not problem of “the Subject” (however much presently eclipsed by that of Identity) is taken up in a sly play on Delmore Schwartz’s “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” in “4th Bear” and the provocatively reflexive “Tale” (which begins: “in a dark forest I found you / not knowing you were / the dark forest and the trail / I was following was the trail / I was making those were / my own breadcrumbs…”).

Those with poetic ears attuned to melopoeia will already have remarked the deft, phonemic harmonies of “the warm reward / of a grain plump duck.” Slobodzian’s undeniable prosodic gift (which I have previously remarked), though present, is at once more under- and overplayed, as it were. Though passages of the quality of that from “Radisson Slough” are not infrequent, the language tends to be plainer, shaped more by rhythm than harmony; at the same time, there is, at times, a marked deployment of rhyme (especially in “Rapunzel”). But Slobodzian’s talent and artistry all come together perhaps nowhere most markedly as in “Pysanka (The Written Egg),” from the book’s first section. Here, a boy, barely out of infancy, sits with his grandmother as she draws a stylus “across the surface / of an Easter egg,” while the boy watches. The poem is a small tour de force in the ease with which it delineates a primal moment of culture (the grandmother’s “fingers [know] these things” and take the boy’s hand) and, reflexively, poiesis itself in the image of “the risen sun / a flaming rose / above an endless line.” These three lines should suggest just how extended an exegesis and appreciation the poem calls for.

Gallant and Cactus Press have surely done us a service in collating and sharing this handful of poems. One can only hope there is some acquisitions editor at a trade press with the savvy to offer to gather them into that full-length volume we’ve been waiting for for too long.

“Hell’s Printing House”: Seventh Column (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Saturday 22 September 2001 The Globe and Mail published an essay article by John Barber “Wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains” (F4). Despite its critical stance toward the then-impending invasion of Afghanistan by coalition forces, the terms of its discourse were so pedestrian my frustrated and bored eye wandered across its six columns. The article read thus, against the grain, appeared oracularly clear, and the experience of that reading what I wanted to communicate in the resulting poem. The sense this reading made to me leaves its trace in minor editorialisations (where the text has been stepped on). This vision into the essence of our imagination of Afghanistan is as forbidding as the country itself: a land of glacierous and desert mountains and sandstorms and tire-melting heat that swallows whole armies. “Cut the word lines and the future leaks through.” Here, English speaks this vision: in dead or obscure words, new compounds and coinages. Syntactically, at root (or so Norman O. Brown told John Cage) the arrangement of Alexander’s soldiers in a phalanx (the Great, too, stopped in Afghanistan), the language has been demilitarized.

Soon after I had composed the poem and printed and bound it in chapbook form, The Capilano Review called for submissions for a special issue “grief / war / poetics” that responded to the then-recent 9/11 attacks. It kindly accepted “Seventh Column,” just not the whole thing, so I had to decide how to excerpt a poem that, despite its disruptive, disrupted syntax, was still, arguably, a “whole.” I opted to have TCR print the first eight and last six stanzas to create a manner of sonnet. That excerpt can be read here, a reading of which I share, below.

“Seventh Column” is, to my mind, a high water mark of my poetic practice, the most carefully, rigorously composed of any of my poems. The lineation and punctuation intentionally follow no consistent rule (some lines are end-stopped, others enjambed, some sentences begin with capitals and end with periods, others not…); words are sometimes broken into their syllables, resulting in new coinages or echoes of an older English (whose meanings are footnoted). The language is thus “made new” and impossible to dominate or domesticate by a hermeneutic will-to-meaning lacking sufficient Negative Capability. Indeed, the poem eluded even my own compositional rigor, somehow making itself circular, ending with the suffix ne- and beginning with the root -glected…

Next month: Luffere & Oþere

New Poem up at Montreal’s own Columba

As my friend Erin Mouré writes, “Aye Columba!” Montreal’s own online poetry periodical has been kind enough to publish a poem of mine along with those of four others, one of whom, Domenica Martinello, was once a student of mine—nice to be in such fine, poetic company!

What’s especially gratifying is the poem selected by Columba‘s editor, Emily Tristan Jones, “Poetry, here, meaning: whatever language helps you sleep at night,” a kind of breathless, dithyrambic work, long a favourite compositional mode of mine, but one ever less frequently indulged.

You can read that poem, and all the others in this Fall edition, here.

“Hell’s Printing House”: X Ore Assays (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

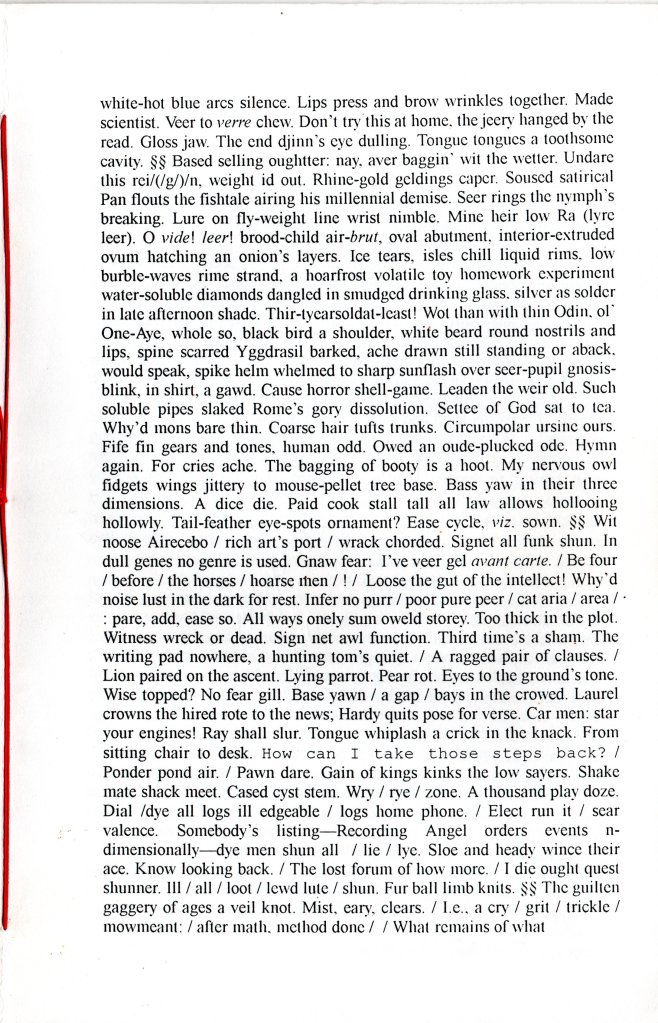

In 1998, I published my first trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems, which collected most of the poems in my previous chapbooks, other than those in On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (which can be accessed here under the ‘Orthoteny‘ tag). I continued to mine and open new compositional veins in line with what I had written, but embarked in a totally different direction in late 2001 with X Ore Assays, which takes inspiration from a number of sources. The most immediate is FEHHLEHHE (Magyar Műhely, 2001) by the Hungarian musician, archivist, editor, writer, and cultural worker Zsolt Sőrés. FEHHLEHHE deploys a wide, wild range of linguistic disruption: disjunctive syntax, polyglottism, collage, sampling, homophony, and portmanteau words, among other means. X Ore Assays is in part an attempt to engage Sőrés’ text in kind, wrighting an English that would imaginably answer his Hungarian. A more remote but profounder influence is the homophonic style that myself and the late Dan Philip Brack (DPB) corresponded in, portions of which were intergrated into his series of short prose works, Letters from Jenny. In our correspondence, very few words were spelled in anything other than a pun, a delirious, funny, private literature, a practice whose linguistic energy I desired to tap in composing the project whose working title came to be X Ore Assays. An even deeper inspiration was the surreal practice of William Burroughs in writing “the word hoard” that was reworked and worked up into his breakthrough novels Naked Lunch, Interzone, The Soft Machine, The Ticket that Exploded, and Nova Express. I aimed to cleave close as I could to that first definition of Surrealism: “Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation,” a much more fraught practice today than over two decades ago. The working title was motivated by this experiment: the texts, composed daily, would comprise a score (x-ore) of raw material (ore) to be assayed, measured, graded, and perhaps refined. However, a kind of ironic, poetic justice intervened. One of the days in this open-ended practice fell on September 11, inserting these texts radically and irretrievably in time’s flow. Curiously, that day was not immediately remarked; rather, hearing of, I think, Billy Collins’ refusal to write of the event almost a week later spurred, ultimately, fourteen more days of response, a supplemental sequence provisionally titled “Sewn Knot.”

That initial twenty, as a gesture of homage, I sent to Sőrés, who arranged to have them published in the Hungarian-language avant garde journal Magyar Műhely. “Sewn Knot” appeared, thanks to efforts of the editor-publisher of Broke magazine Andrea Strudensky, in the Canadian periodical dANDelion. “X Ore Assays” and “Sewn Knot” have presently been combined and are being revised and refined under the working title “after FEHHLEHHE,” which makes up the opening section of a manuscript-in-progress tentatively titled Fugue State.

The sections responding in real time to 9/11 were not among those included in the chapbook; they can, however, be read, here. I reproduce, below, a page from the middle of the book, and read the day’s work beginning “Wit noose Airecebo..”

Next month: Seventh Column (2001).

“Hell’s Printing House”—Gloze (1995)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Gloze is my first self-produced, self-published chapbook, inspired by Pneuma Press’ Budapest Suites. As I note in the prefatory remarks to this series of posts, Gloze and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery were the works that represented me during my European Tour of 1996 and for some years after, until the publication of my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central and other poems in 1998. The cover is an original artwork of my own, an aleatoric painting in acrylic and collage.

Contents

- Grand Gnostic Central

- After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort

- Smalltalk Hamburg 91

- Two

- Three

- In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14

- DP Channels Baba G

- Arachnophobia Prima Facie

- Five

- Thou, Palæmon

- Transcription

- Six

- “As I delighted with the enjoyments of torment…”

- Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli

- Otto (1)

- Á Québec

- ‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath

- Horizontal Gold Golden Mercury

- Tonight

- Green Wood

- Ten

- Marmitako

- Will of the Wisp

- Coda: Gloze

“Grand Gnostic Central” is, here, five prose poems (one of which can be read here) and the poem “Tonight, the world is simple and plain.” All poems hyperlinked above are “published” on Poeta Doctus; “Gloze” is represented by a YouTube rendition by “Jake the Dog.”

Although I had yet to publish a full-length trade edition, the poems collected in Gloze already gather work representative of a decade’s work and engagement with the poetry of my peers. At least the prose poem about Wittgenstein and the poem beginning “Tonight, the world is simple and plain…” along with that engaging Meister Eckhart (“After a Legend of the Prior of Urfort”) were composed during my graduate studies (1986-89), when I was labouring to write a way between and with poetry and philosophy, the topic of my master’s thesis. Nevertheless, my concerns were hardly exclusively abstruse: “Smalltake Hamburg 91″ addresses racism,”Thou, Palæmon” the first Gulf War, and “Á Québec” québecois nationalism. As down-to-earth, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury” and “Marmitako” ruminate on the alchemy and joy of preparing our daily bread. At the same time, “Horizontal Gold Noble Mercury,” with its allusion to alchemy and the Hermetic philosophy, betrays an interest in more recherché matters, whether the psychicomagical experimentation of Willliam Butler Yeats (“Otto (1)”) or ghost stories from my grandparents’ generation (“Will of the Wisp”), whose Hungarian side are given a nod in the poem “‘Toponomy’ After a Theme von Etienne Tibor Barath,” no less a satire of, again, ethnonationalism. “DP Channels Baba G” is a terse condensation of the life of a Hindu saint, a gesture toward an attention to more “spiritual” matters, a leitmotif in much of my poetry. “Arachnophobia Prima Facie” is more psychological, exploring a fear of spiders that reaches back to my earliest memories. “In 1978 When Louis Zukofsky Died at 74 I Was 14” is a humorous poem about poetic influence and stature.

But, apart from such thematic concerns, many of the poems are more overtly formal, compositional or artistic in their motivations. As I remark with regards to the poem “Six”:

Back in the early Nineties of last century (!) when I wrote this poem, the fashion among many Canadian (at least) poets was to write sonnet sequences. By chance, one day, I wrote a poem (“I know the Aurora Borealis” in Grand Gnostic Central) that happened to have fourteen lines. That chance (which to my ear happily rhymes with ‘chants’) occurrence began an ongoing, half-satirical series of accidentally-fourteen-line poems I called variously over the years “soughknots” (literally “air-knots”) and here “sonots” (so not sonnets!).

All the numbered poems are such sonots. Aside from the prose poem about Wittgenstein in “Grand Gnostic Central,” the others are inspired by early ‘pataphysical prose poems of Chris Dewdney’s. “Transcription” is a sequence of improvisations, likely motivated by an engagement with the spontaneous poetics of the Beats, which I had studied intensively during a memorable summer course in my graduate studies. “Tonight” pretends to this mode, but frees itself from it by means of a litotic irony turning on the ambiguity of a pronoun. “As I delighted with the enoyments of torment…,” “Holy Crow Channels Scardanelli,” and “Gloze” are all experiments in collage poetics. “Gloze,” especially, is a formal innovation of my own, prompted by the Wittgensteinian dictum that “meaning is use.” “Gloze,” and other poems, collate all the meanings of a word or phrase and represent them cubistically by means of the examples provided by the Oxford English Dictionary…

Of all the poems in Gloze, I’m most moved to share “Green Wood,” a poem that synthesizes much of the influences and experiments present in the book. On the face (and “ear” of it), it is reminiscent of the rhapsodic poetry of Allen Ginsberg and others. However, it’s opening line nods to a more radical influence, a translation from Lucretius by Basil Bunting. However much it might be said to deal with personal experience, it tends toward a more objective, metonymic, paratactical presentation, and is guided by a shy, mystical sensibility, perhaps most visible in its attention to synchronicities. Below, you can hear recordings of that poem, along with a performance of Bunting’s translation, a poem I was given to recite at the beginning of my poetry readings at the time.

“Green Wood”

Bunting’s Lucretius’ “Hymn to Venus”

Next month, X Ore Assays (1st Score), 2001:

“Hell’s Printing House”—Budapest Suites (1994)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Budapest Suites is the first published version of the titular poetic suite that later appeared, slightly revised, in my first, full-length trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems (1998). It, along with all books issued in the Pneuma Poetry Series, was designed and printed by my friend Richard Weintrager.

Contents

- “Apply what you know to what you feel that’s more than enough”

- “Mount Ság”

- “That he might…”

- “The chest-high white-haired Swiss woman asked…”

- “I went down to Bibliomanie”

- “Dan and I waltzed hopfrog…”

- “You don’t just follow an impulse do you?”

Budapest Suites collects poems written during and after a 1991 trip to Europe (my first!), whose highpoint was a visit to Budapest and Celldömölk, the hometown of scholar poet friend Kemenes Géfin László, there to be honoured for his literary work and to launch his avant garde epic work Fehérlófia (the son of the white horse). On that occasion, we visited the extinct volcano on the outskirts of town Mount Ság (Sághegy) where Géfin had hidden out during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 before escaping over the border to Austria. Géfin was struck by the lushness of the locale, so much he was moved to remark, “There is a god here!”, the opening line of the second suite.

In Budapest, I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of some American ex-pats, among them, writer Dan Philip Brack (DPB), “Dan” in the opening line of the penultimate suite. Let’s attribute the epigraphs of the first and last suites to him. The fourth suite commemorates a visit to the National Museum. The third suite, as well, was written in situ. The fourth suite was composed after returning to Montreal; its being slightly confusing might be attributable to its being “a mystical poem,” as Hungarian poet Tibor Zalán called it.

The poem recorded below is the third suite. Darius Snieckus, author of the inaugural chapbook in the Pneuma Poetry Series, The Brueghel Desk, was so impressed when he read it, he insisted I not “change a thing!”. His anxieties were not unfounded, as up to and into the writing of the Suites, I had been an obsessive reviser: I still have the notebook with the seventeen (at least) versions of “Mount Ság” worked over that one afternoon, including the Hungarian translation by Zalán and András Sándor, which was read to Géfin on site in honour of the visit.

It was in revising the fourth suite that the most recent, nth version turned out to be identical to the very first. It was then I learned the truth of William Blake’s dictum “First thought best in Art…” From that revelation on, my compositional practice was to write, then carefully study what had been written to understand its spontaneous rightness before cautiously making slight alterations, only in order to bring out the energy of that original impulse all the better. It was Joachim Utz, one my most careful German readers, who noted that the Budapest Suites marked a “breakthrough” in my poetry.

Next month, Gloze (1995)…

Announcing “Hell’s Printing House”

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

First up, Budapest Suites (Pneuma Poetry Series, 1994)…

“To praise, that’s the thing!”

“Being a poet,” at least an anglophone poet in Canada, can seem sometimes near impossible. Sheer incomprehension and yawning indifference can drive one to despair, let alone those of us already perhaps too self-critical or reflective. At times, however, we may be fortunate enough to encounter those with heart enough to speak their appreciation for our work in our hearing. It was during one dark patch I called to mind those who had so praised me, remembering them in the following poem (which hopefully remains unfinished!).

Leave a comment

Leave a comment