Archive for the ‘George Slobodzian’ Tag

On George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa

Culture must be—as the word itself might suggest—cultured, seeded and carefully tended. Such care takes many forms in Canada, from ever-diminishing (if however appreciated) government funding, to the selfless, meagrely-rewarded efforts of those who—in the case of our literary culture—publish small magazines and books of poetry, to more grassroots efforts.

In recent years, in Montreal, Devon Gallant and collaborators have cultured an urban poetic garden, organizing the Accent Reading Series, which combines an open-mic (as polylingual as the city) and a spotlight on one or two featured readers, and which has, accordingly, gathered a small, poetic community. One of the fruits of this endeavour is Cactus Press, which, to date, has issued over thirty chapbooks and the first trade edition of the unnervingly-talented Willow Loveday Little, (Vice) Viscera (2022).

One of the newest of these chapbooks is George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa, his second with Cactus Press. Apokryfa gathers eighteen poems, old and new, organizing them in three sections, “In the Garden,” “Et Homo Factum Est,” and “Tale.” The first reflects on childhood and youth, the second works up and on, more-or-less, Catholic mythology, while the last reworks fairy tales. However much at first glance these sections might suggest a progression from autobiographical truth to overt fiction, a more canny, poetic sensibility is at play that subverts such too-easy, hard-and-fast distinctions.

But this sophisticated sensibility is only one aspect of these eighteen poems, which, perhaps more importantly, reveal a poet at the top of his game. While, from the “Tale” section, “Other Dwarves” and “Deliverance” (a riff on “Rapunzel”), might seem relatively light, they are not without their wit (in the case of the former) or rich suggestiveness (in the case of the latter). Most of the poems are, however, so to say, more thematically substantive. “Radisson Slough,” recounting how the boy speaker “Out hunting with [his] father / and brothers, …was the dog,” concerns as much a moment in one’s lifelong loss-of-innocence as much as, perhaps, weightier epistemological matters when “in search of the warm reward / of a grain plump duck,” the boy finds “instead the corpse // of an abandoned crane / half-submerged and corrupt, / its great wings still engaged / in a sort of flight until” he touches it, and it sinks. “The Annunciation” in the chapbook’s second section, “Et Homo Factum Est” grimly recasts the Archangel Gabriel as the agent of some unnamed totalitarian regime with an uncannily ironic gift of prophecy who foretells the life of the expected son, a malcontent (and who wouldn’t be under such a system?) who leads “an entirely unremarkable childhood,” in the end only to “be taken / into the appropriate custody” to finally succumb “to his diseases.” And, in the book’s final section, that persistent question if not problem of “the Subject” (however much presently eclipsed by that of Identity) is taken up in a sly play on Delmore Schwartz’s “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” in “4th Bear” and the provocatively reflexive “Tale” (which begins: “in a dark forest I found you / not knowing you were / the dark forest and the trail / I was following was the trail / I was making those were / my own breadcrumbs…”).

Those with poetic ears attuned to melopoeia will already have remarked the deft, phonemic harmonies of “the warm reward / of a grain plump duck.” Slobodzian’s undeniable prosodic gift (which I have previously remarked), though present, is at once more under- and overplayed, as it were. Though passages of the quality of that from “Radisson Slough” are not infrequent, the language tends to be plainer, shaped more by rhythm than harmony; at the same time, there is, at times, a marked deployment of rhyme (especially in “Rapunzel”). But Slobodzian’s talent and artistry all come together perhaps nowhere most markedly as in “Pysanka (The Written Egg),” from the book’s first section. Here, a boy, barely out of infancy, sits with his grandmother as she draws a stylus “across the surface / of an Easter egg,” while the boy watches. The poem is a small tour de force in the ease with which it delineates a primal moment of culture (the grandmother’s “fingers [know] these things” and take the boy’s hand) and, reflexively, poiesis itself in the image of “the risen sun / a flaming rose / above an endless line.” These three lines should suggest just how extended an exegesis and appreciation the poem calls for.

Gallant and Cactus Press have surely done us a service in collating and sharing this handful of poems. One can only hope there is some acquisitions editor at a trade press with the savvy to offer to gather them into that full-length volume we’ve been waiting for for too long.

Chez Pam Pam: new volume from George Slobodzian

George Slobodzian, a poet-friend whose work I’ve admired and often lauded from the  start (over thirty years ago, now) finally has a new volume of poems out: a hefty forty-five-page chapbook Chez Pam Pam from Montreal’s Cactus Press.

start (over thirty years ago, now) finally has a new volume of poems out: a hefty forty-five-page chapbook Chez Pam Pam from Montreal’s Cactus Press.

For now, it’s readable only as an e-book (for all of CAN$5.00). I look forward to holding the physical volume in hand. In the meantime, you can whet your appetite for the real thing with Slobodzian’s poetry, which is, more importantly, the real thing.

“the haven from sophistications and contentions”–a translation of George Slobodzian’s “Happy Hour”

Today, I read on Facebook a friend rightfully take to task a new anthology of Canadian poetry for its lack of translations. Later, I read how one poet tweeted squibs over a retrograde and self-indulgent column that riled a friend of the columnist to snark back via his own blog while everyone ignores the column’s sentiment was preemptively taken down by happy synchronicity days before. A poet-publisher laments the roadblocks to conversation and posits turning his back on the futility of finding the like-minded to work it all out in private in his journal instead. Meanwhile, the work goes on, here, a translation, from English to French, of a fine, understated lyric, “Happy Hour”.

George Slobodzian’s “Poems for the Old Guy Who Used to Live Here”

George Slobodzian’s “Poems for the Old Guy Who Used to Live Here”

As translating machine Antoine Malette writes: read it in English or in French but read it!

Click on the thumbnail to get yourself a copy of the collection that includes this sequence.

Slobodzian’s “Ars Poetica” en français!

Slobodzian’s “Ars Poetica” en français!

The indefatigable Antoine Malette has produced another translation of a fine, uncollected poem by George Slobodzian. Both the English-language original and Malette’s translation are readable at the link!

More Slobodzian en français

Antoine Mallette produces another excellent French-language translation of a poem by George Slobodzian deserving of greater dissemination, in any language. Read it here: Excursion à Woodlawn (Woodlawn Excursion) – George Slobodzian @ . :: Antoine Malette.com :: ..

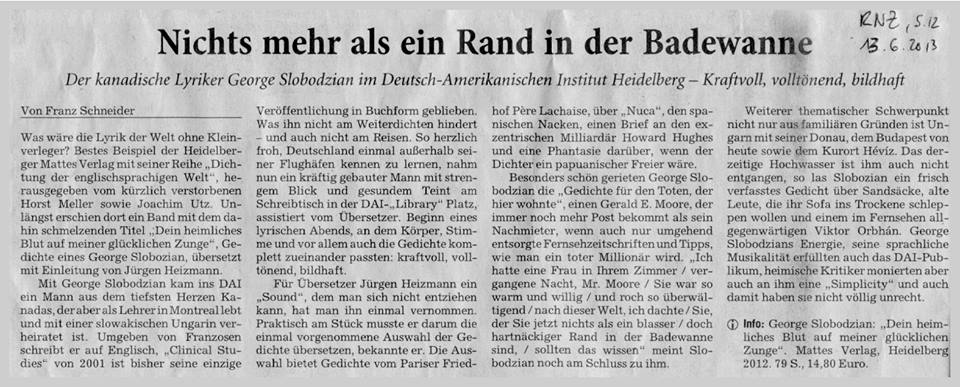

from the Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung 13 June 2013

When was the last time you read a review of a poetry READING in a Canadian newspaper? Well, they do it in Germany! Here, of George Slobodzian launching a German-language selection of his poetry in Heidelberg.

Prière pour Zoë (Prayer for Zoë) – George Slobodzian

Prière pour Zoë (Prayer for Zoë) – George Slobodzian

Antoine Malette provides a French-language version of a striking poem from George Slobodzian’s Clinical Studies.

You can read Malette’s appreciation (in French) of Slobodzian’s poetry here.

My appreciation of Slobodzian’s poetry is here.

A French-language notice of the German translation of George Slobodzian’s poetry!

A French-language notice of the German translation of George Slobodzian’s poetry!

Antoine Malette has posted some illuminating and appreciative words concerning the poetry of George Slobodzian and the just published German-language translation of his poems Dein heimliches Blut auf meiner glücklichen Zunge (trans. Jürgen Heizmann).

Good to see Slobodzian get some well-deserved polyglot appreciation!

On the Poetry of George Slobodzian

This past New Year’s Eve I pulled down a couple of poetry books from our host’s bookshelves and shared two favourite poems with the collected company: William Carlos Williams’ “The Sparrow” and George Slobodzian’s “Woodlawn Excursion” from his Clinical Studies. As I flipped through this collection from 2001, I was struck by how much difficulty I was having choosing just one poem to read, every one was so different and so accomplished. I was moved, then, to try to rectify how unjustifiably unknown and undervalued Slobodzian’s poetry is. To that end, I post here a very slightly emended version of a review I wrote that appeared first in Vallum shortly after Clinical Studies was published and in answer to the dismissal, remarked below:

Gertrude Stein writes somewhere that one writes for oneself and strangers. However much today’s poet might feel he or she writes for that audience of one, the reviewer — or this reviewer, anyway — finds himself as isolated. Our literary culture is so atomized, the reviewer needs to don a pedagogical, before a critical, role to avoid being merely partisan or indulging the amateurish ad-copy that passes for so much of our critical discourse. This pedagogical demand is acutely apparent in the case of George Slobodzian’s Clinical Studies. Its publication met with a singular critical attention: one relatively immediate derisive dismissal, and belated inclusion in an omnibus review. This reception is understandable. Slobodzian’s lyrics are difficult and challenging, not because they toy with the intentional obfuscations of our latter-day avant-gardistes, but because of their hyperbolic understatement. They are so conversational, so unassuming, their wit, irony, and music are too subtle for most. Their classical clarity and lyrical euphony are balanced by their being often quite literally obscene, presenting what is conventionally “off-stage.”

A reader with time to reflect might well note this thematic harmony in the volume’s title, that of the first poem, and its subject matter. Clinical Studies and “Clinical Studies” both begin

Upstairs among photographs

so hideous

we were not allowed

to view them…

These photographs are medical, documenting “…the single / and half-breasted women / of medical science” and “human genitalia / eaten beyond recognition”. The poem’s persona, who takes “such pleasure turning / neighborhood stomachs / with” his father’s stash of forbidden pictures, dreams of becoming a surgeon himself to lift away the photographed anonymous subjects’ censor-strips and to “give them back their eyes”. The collection’s title-track suggests an approach to the volume as a whole. The book is an album, shown us, yes, with an impish delight in our squeamish shock, but one bound by at least two sensibilities, one clinically objective, the other humane and caring, imaginably even empathetic.

This attention to the body is often itself bawdy, in the best tradition that stretches from the outrageousness of Catullus, through the scatological hilarity of Dante, Chaucer, and Rabelais, to Joyce, Gottfried Benn, and others. This ubiquitous reference to the body and its functions reminds us corporeality is the inescapable condition of human experience in the first place, regardless of the repressive resentment against incarnation like that of Calvin “contemplating hell-stench on the shitter”. A topic as respectable as History is presented in the forms of the last Passenger Pigeon reflecting over Doughboys who “…sink deep / into their own shit / in the trenches” and a tour guide repeating his memorized spiel about a Classical “unguent basin, carved / out of solid excrement”. Howard Hughes appears with his “bottled urine”, “fingernails / beginning to curl”, and “bedsores”, watching for the umpteenth time his favorite Cold War thriller Ice Station Zebra. Even biotechnicians make an appearance, culturing “[h]uman skin. / From the foreskins // of newborn men”.

Slobodzian’s physicality is as sanely salutary as it is satirical: twenty-three of the book’s forty-five poems concern that extended body made up of family and lovers. Slobodzian is at his funny, gentle, tender best here. The three elegies for his mother, the poem for his father’s wedding (he, an “…old bull / in his winter meadow, / balls hanging low and blue”), and Slobodzian’s trademark “Zoëms” (poems for his daughter Zoë) are at the heart of the volume. The “Prayer for Zoë” is a tour de force whose rhythms echo the Hail Mary and whose invocations reincarnate Her as the literal mother she sublimates and hypostasizes. She becomes

Our lady of excrement,

of multiple comings

and goings, generation

and decay, perpetual

motion, wholly cloacal,

mother and father of slime,

the glistening slime

rimming the fetal pool…

Of course, there would be neither mothers, fathers, family, or lyric poetry without desire, and Slobodzian’s love lyrics are as full frontal and technically adroit as those addressed to relatives. They range over the delightful play of courtship (“If I Were Your Papuan Suitor”), warm sensuality (“Nuca”), the bitter ashes of burnt-out love (“Cold Fusion”), and the softening tints of nostalgia (“À la Recherche du Temps Perdu” and most notably “Sustain”).

Of course, despite many protestations to the contrary, poetry is not merely some special subject matter, but what the German Romantics called “the mother-tongue of the race”, that — as Carlyle reminds us — whereby we “sing what we have to say”. An appreciation of the sheer linguistic craft in Slobodzian’s poetry demands an excursus all its own. Suffice to say here, it both revels in its own lithe sinewy power and in its delicious sensuousness. The former might be best exemplified by an example I do not even have to read to transcribe, it has stayed with me so over the many years I first heard Slobodzian recite it. His early poem “Suffrage” is about overhearing two young women in the bus seat ahead discussing the Cosmo they are reading. The poem’s last lines are a judgment on the debasement of the Human Form Divine and a justification of the persisting need for lyric poetry:

And listening

it occurs to me

that love must be

a stalwart beast

to haul such crap

and remain intact

The tongue of that beast that hauls the delights of love and sheer human being into the present is capable of delicate musical delight, too, such as the reflective pleasures of “Credo Tropicanum”, the first lines of which I leave with you:

Spooning papaya uterine rind

onto genital tongue

and holding it there

ripening

For those whose taste has been whetted by this review, the latest and densest sample of Slobodzian’s poetry can be found in the recently published Show Thieves 2010 anthology.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment